SVA Features asset

This fall, the renowned satirist, illustrator and longtime faculty member in BFA Illustration and SVA Continuing Education Steve Brodner will be honored with SVA's 31st Masters Series Award and Exhibition. "The Master's Series: Steve Brodner" will be on view from October 5 through November 2 at the SVA Chelsea Gallery. Watch our video profile of the provocateur—a self-described "aggravator"—above and read our Q&A with Brodner below to learn more about his career and the state of political art today.

Your career spans five decades, which includes being the first living illustrator to receive a career retrospective at the Norman Rockwell Museum. You've also published numerous books, served as the editor of Artists Against the War, and worked with clients like Esquire, The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Columbia Journalism Review, The Nation and The Washington Post. Tell us about your career path up until now. Where did it all start, and how did you know you were on the right track?

The whole thing is a mystery to me. I was absolutely certain I would have a career, but I couldn't tell you right now how I knew. Every step of the way there was someone or some organization giving me the signal that I wasn't crazy to think that this could happen. So for years before I was successful, I was getting published in places—each one a little bigger and more important than another. It was easy to have self-confidence under those circumstances.

In the beginning, however, where did the energy and belief come from? I have no idea. I was a needy kid who was pretty much ignored. That can be a powerful combination of conditions. I grew up in a very political time, a little like now, but much clearer in terms of media and its role in society. People couldn't just decide to choose nonsense for news. And cartoonists were important. Herblock was king of them. [Al] Hirschfeld in the Times, though not political, showed the power of graphics. Then [Ralph] Steadman in Rolling Stone, etc. These were dynamic influences.

Do you see political art as an act of resistance?

I see it as an attempt to resist bullshit. Political cartoons only work if they try to tell the truth. That's what they really are: a truth-extracting device. The best ones make the best truth juice. Since liars, thieves, moguls, corrupt politicians and tyrants all must have bullshit to feed to their gangs, a cartoon or caricature can be very dangerous to them. As dangerous as the truth.

You've been creating satirical illustrations for decades. As someone immersed in politics and world affairs, what have you seen change over the years?

We have seen so much that a good list would take all night. We have gone from Jim Crow to a black president. We went from massive pollution to much cleaner air and water. From universal cigarette smoking and denial of gay rights and women's rights to the opposite. Wars used to be easily started, then shunned, then again begun everywhere at the drop of a hat—or bomb. Then finally a massive shift to the hard right after an aberrant election and, soon, back to sanity, I am betting. All of this during the rise of—and not for a second unaffected by—computers, now in everyone's pocket and ear, 24/7. Change now comes minute by minute. I can understand the need to disconnect. But democracy demands that we don't, especially in critical times.

Last fall, you co-curated "Art as Witness: Political Graphics 2016-18" at SVA, which featured more than 200 politically motivated works from 53 artists. What was the process like for selecting the artwork included in that show?

That marvelous show (I say that about the artists, not my contribution) came at a time of anguish about the rise of the Trump mob. The artists addressed the fear of fascism that's come to the U.S. And time has proven them, if anything, conservative. The choices were made by myself and curator Francis DiTommaso. The breadth and depth of the work being done now is amazing. We should plan another show soon!

Steve Brodner, The Court of King Donald I, 2017. From Los Angeles Times, January 2017, art directors Wes Anderson, Susan Brenneman. Courtesy of the artist.

Finally, what are your top five most influential political artworks or artists, from your perspective?

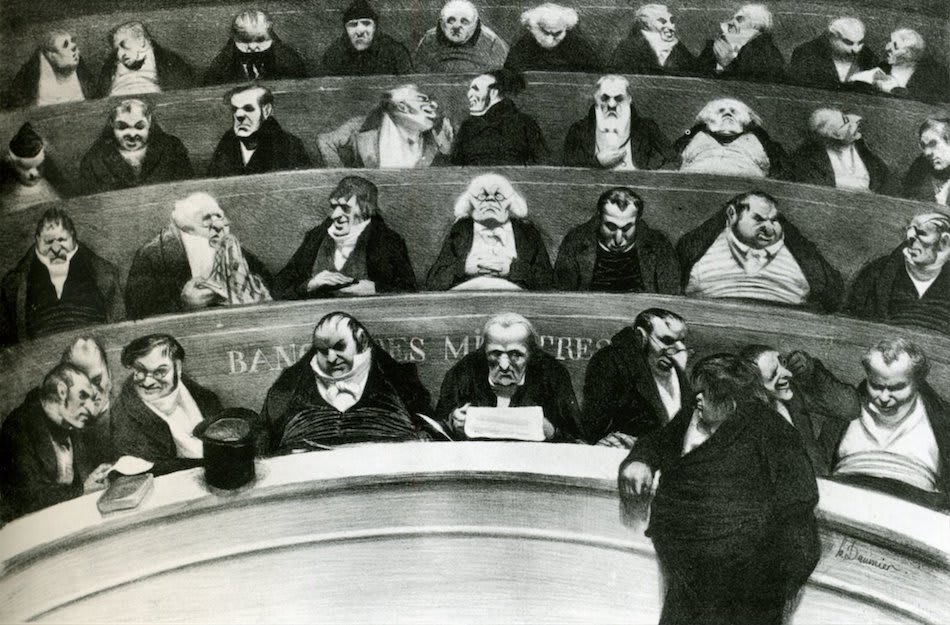

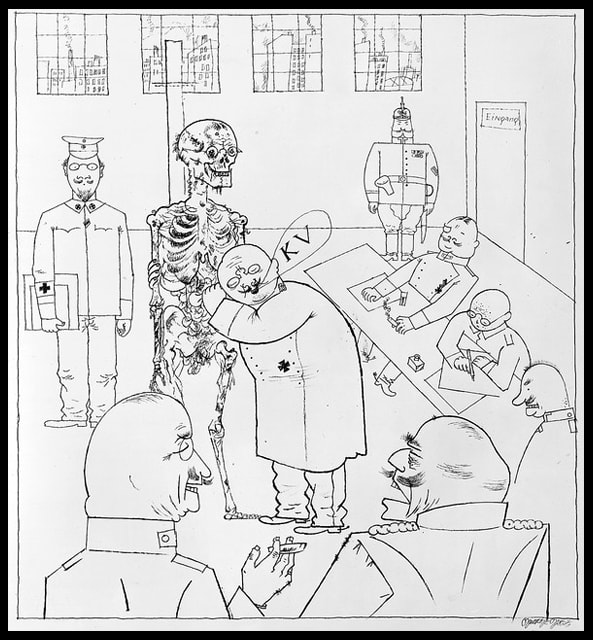

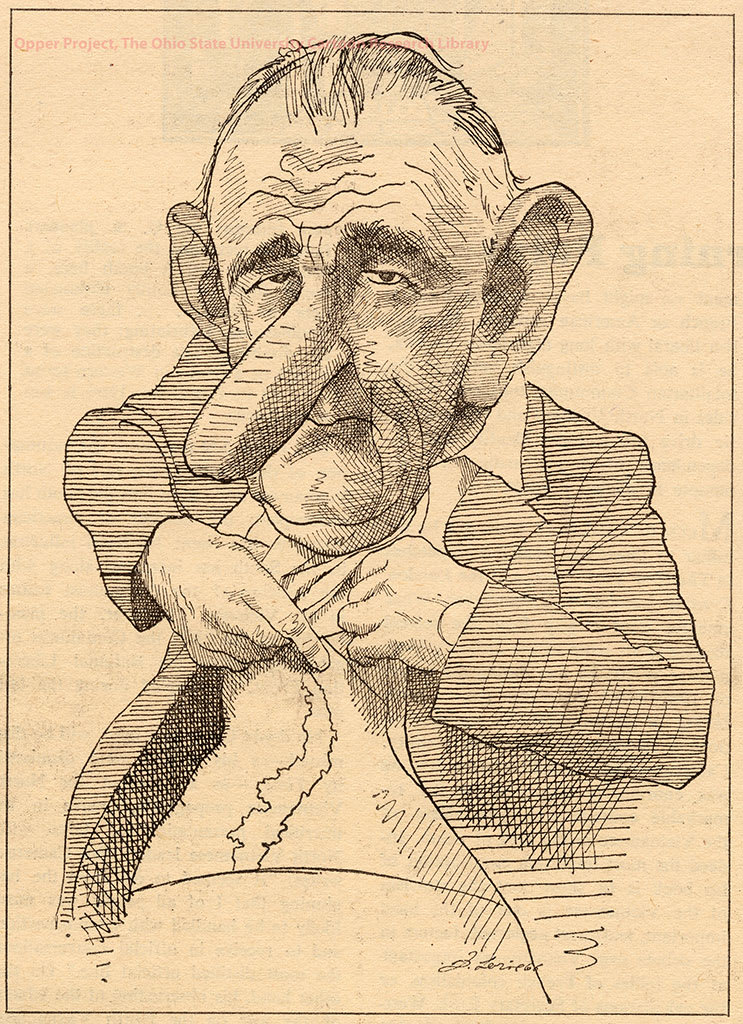

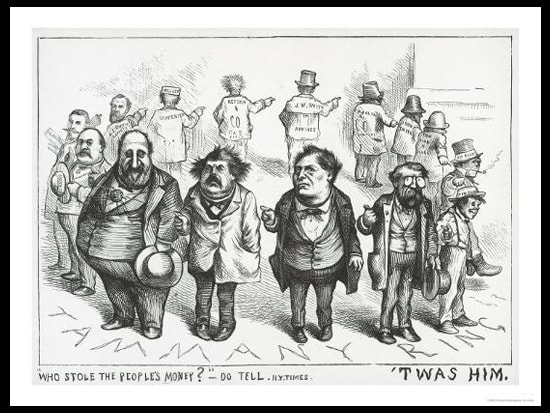

It is not possible to discuss the five best of anything. But I would look at the work of David Levine on LBJ and Nixon, David Low on Hitler, George Grosz on oligarchs, John Heartfield on Hitler, Thomas Nast on Tweed, James Gillray on Napoleon, Daumier on Louis Philippe, Goya on war, Herblock on McCarthy, Bill Mauldin on WWII. And then allow yourself to be thrust further in all the different directions these point in.

Here are five for argument's sake:

Honoré Daumier, The Legislative Belly, 1834.

George Grosz, Fit for Active Service, 1918.

David Levine, Lyndon Johnson, 1966.

David Low, Rendezvous, 1939.

Thomas Nast, Who Stole the People's Money?, 1871.

Honoré Daumier, The Legislative Belly, 1834. Via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

George Grosz, Fit for Active Service, 1918. Via The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

David Levine, Lyndon Johnson, 1966. Via Forum Gallery, New York.

David Low, Rendezvous, 1939. Via University of Kent, British Cartoon Archive.

Thomas Nast, Who Stole the People's Money?, 1871. Via ThoughtCo.

"The Masters Series: Steve Brodner" opens on Saturday, October 5, at the SVA Chelsea Gallery, 601 West 26th Street, 15th floor. A reception and awards ceremony will be held at the gallery on Thursday, October 10, from 6:00 to 8:00pm, and Brodner will give a talk on his work on Wednesday, October 30, from 7:00 to 9:00pm, at the SVA Theatre, 333 West 23rd Street. All events are free and open to the public.