To help bolster its brand, RapCaviar—a popular playlist on the music-streaming service Spotify—has hosted concerts featuring some of its most-listened-to artists. Image courtesy Spotify.

The visual aspects of the music world have always been powerful tools for establishing performers' identities and monetizing an art form that is, fundamentally, meant to be heard rather than seen. Dynamic album covers, innovative videos, ambitious stage setups and eye-catching merchandise have been staples of popular music for decades. In recent years, though, nontraditional design has come to the forefront, intersecting with the entertainment industry—and, by extension, the tech industry—in ways that seemed more like science-fiction fodder just 20 years ago.

As the 21st century arrived, peer-to-peer file-sharing sites like Napster built the "old" music industry's coffin; the introduction of the iPod, in 2001, nailed it shut. The idea that thousands of songs could fit in a pocket effectively ended the physical album's reign as popular music's dominant format. Ten years later, the introduction of services like Spotify, which allow consumers to listen to music on demand without downloading any files, gave rise to the streaming era. Now, discussions about how fans access their favorite music are almost as commonplace as discussions about the art itself.

An installation view of the 2017 Brooklyn Museum installation "RapCaviar Pantheon," a branding project of Spotify, the music-streaming service, which featured robot-fabricated sculptures depicting the popular musicians 21 Savage (left), SZA (center) and Metro Boomin (right). Photo by Driely Carter, courtesy Spotify.

Saba Singh (MFA 2017 Interaction Design) is a UX, or user experience, designer at Amazon Music. Many of her day-to-day considerations don't hinge on how to curate music based on individuals' tastes, but in finding ways to suggest music that complements a particular time of day, location, activity or even type of weather.

"To a large extent, we're talking about people's expectations and behaviors when they're listening. How does music support their activity? How does it enhance it?" she says. "A lot of times, when people are listening, they might have a specific intention or role they want the music to fulfill. So we're thinking about how, for example, we surface the right kind of music to you because you're dancing or you're cooking."

The rising popularity of smart speakers and the virtual assistant—Google Assistant, Apple's Siri, Amazon's Alexa—adds an additional layer of complexity to the work of someone like Singh, for whom the interaction between human, robot and music opens up endless possibilities. "We're not just looking at an app and selecting what the music is, but we're doing a lot of conversational stuff because of how people speak to Alexa. They request music," she says. Sometimes, the requests are specific. Other times, perhaps when a song title isn't known or the desire is for something broad, it is incumbent on the artificial intelligence to do the guesswork.

"So what's slightly different is that we get to look at conversation as design, which I think is very interesting and very different from anything I studied."

An Amazon Music display screen. Saba Singh, a UX designer at Amazon, is one of many who are working to make the online retail and streaming service's platform as intuitive and targeted as possible. Image courtesy Amazon.

Singh sees this type of user–service interaction as the plausible next step beyond the current vogue for largely algorithmic mood- and artist-based playlists and programming, which, like radio DJs, cater to listeners who aren't interested in actively participating in music selection.

"I definitely have a pretty strong bias here, but I'm inclined to say [the future] would be all screen and all conversational." She likens it to how people have become used to customizing their coffee-shop orders, going beyond strict menu options to specify the amount or type of creamer, or ask for extra shots or half-decaf. Imagine, instead, a listener requesting a fast-paced song, from the mid-'90s, with no hi-hats and synths. "The ability to be that granular with music is something that voice technology allows," she says. "I expect that's where things are going—people are going to be more demanding about what they want, rather than more passive."

AI that discerning may be a ways off, but another, more immediate challenge for streaming services is how to bridge the gaps between digital and physical platforms, and between artists and fans. Tal Midyan (BFA 2013 Advertising) is a senior art director at Spotify, and one of the brains behind the company's "RapCaviar Pantheon" exhibition, first installed in the Brooklyn Museum in 2017. That show featured life-sized, robot-fabricated statues of the musicians SZA, 21 Savage and Metro Boomin, briefly transforming something that only existed online—Spotify's RapCaviar playlist, an evolving selection of songs considered to be one of the most influential and popular forces in music today, with the power to break new artists—into a tangible entity. (A second "Pantheon" exhibition, honoring a new group of artists, appeared in the museum this April.)

Posters advertising a concert sponsored by Spotify's popular RapCaviar playlist and featuring Lil Uzi Vert, one of the music-streaming service's most-listened-to artists. Image courtesy Spotify.

"We were developing branding for this playlist so that people would know it as an editorial voice," Midyan says. "The idea was to make something like a year-end list but in a way that no one else would do."

When Midyan joined Spotify in 2016, his task was to help turn the platform, at that point known more as a functional medium than a glossy destination, into the powerful brand it is today—that is, to render the power of music visually, and in a way that compelled consumers to not only listen but to use the app to do so. His designs must exist in the real world (like the "Pantheon" statues or on massive billboards) and in the digital sphere (like the interactive website that Spotify created to support 21 Savage's debut album); they also must reinforce the images of any of the artists they feature. "We've created these really good systems," he says. "But how do you give users that feeling of when you go to a record store? How do you maintain that freedom and expression while still making it suitable for an app that’s easy to use?"

Concrete answers are few, but the creative potential is infinite. The rise of streaming means fans and artists alike have numerous options. The old formats of recorded music still exist, finding audiences among those who still appreciate the feeling of holding a record in their hands. And while smart phones and streaming services may have all but relegated physical media to the peripheral, for Singh and the team at Amazon, there remains some need to have one foot in both realms.

"We do have a huge base of people who still purchase music on our platform," she says, which, much like streaming, still means catering to users' needs by surfacing the music they might want to buy via algorithm. But the limitations fall away when the focus changes from commerce to experience. "The physicality of music is being given less value ... so we're dealing with interaction with a screen most of the time. It's allowed us to enhance certain experiences—for example, playing music on any device in your house. What's been given is a feature set that allows flexibility with how you want to listen."

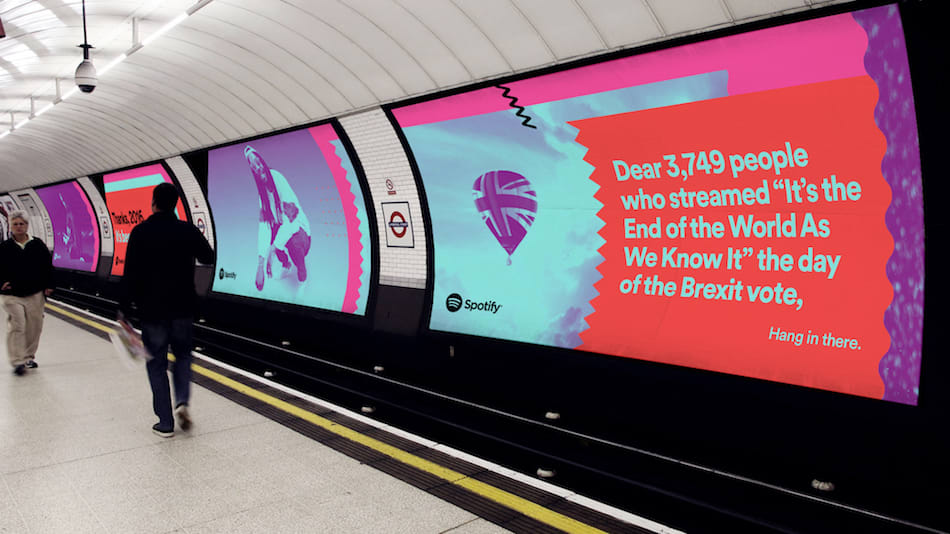

Ads in London from Spotify's "Thanks 2016, It's Been Weird" global campaign, the music-streaming service's first major branding effort. Image courtesy Spotify.

With the help of designers like Singh and Midyan, music becomes an immersive and immediate experience, available at any time and place. Listening habits become the concern of companies from front to back, as platforms, like the artists themselves, race to keep up with consumers who are now accustomed to soundtracking their everyday lives. The goal is no longer to just sell music but also to sell convenience and seamless integration, which means apps that are as intuitive and nimble as they are aesthetically pleasing.

"I'd like to believe that what the user sees, at the end of the day, is the [visual] design. What they're not able to see is all the engineering and back-end effort that makes what they’re seeing possible," Singh says. "A lot of the work designers end up doing is working around and enhancing the behaviors that consumers already have."

Streaming has created well-publicized dilemmas for the industry. Diminished profit margins make it harder for musicians to support themselves through their art, while listeners have become ever more insatiable in their desire to have instant access to all of it. But designers like Midyan face a unique quandary of their own: balancing the interests of user, platform and artist all at once. That is, how can musicians use an app like Spotify, which is inherently an audio-oriented experience, to support their releases in a manner that appeals to fans both visually and experientially?

"I think design for music should always be about the artist or an extension of the artist's expression," he says. "I also feel like our role is to kind of get out of the way as a brand. That's always the challenge, because people don't want Spotify—they want music."

A version of this article appears in the spring 2019 Visual Arts Journal.