Among design legend Milton Glaser’s many accolades and designations, the longtime faculty member and SVA’s acting chairman of the board holds the additional distinction of creating the greatest number of posters in the College’s longstanding "Subway Series"—a total of 24 over 50 years. On Monday the MTA installed his latest campaign on subway platforms all over the city. The three designs display Glaser's emphatic commitment to justice through social engagement and deeply held belief in the power and potential of art.

Since the mid-1950s, SVA has featured the work of practicing faculty members as part of a promotional initiative staged in New York City’s subway stations. The "Subway Series" posters promote the College and showcase the individual artist’s vision, offering a thought-provoking and visually exciting appeal to potential students and fellow New Yorkers. Featured artists have included Louise Fili, Steven Heller, Stefan Sagmeister and Yuko Shimizu (MFA 2003 Illustration as Visual Essay), among many others. SVA Executive Vice President Anthony P. Rhodes has served as creative director for the posters since 2007.

In a new video for SVA (below), Glaser discusses the unique audience the posters address and the exposure they have afforded him, as well as his rediscovery, following an alteration to his iconic "I Love NY" logo in the wake of September 11, 2001, of the profound impact graphic choices can have on a viewer's consciousness. "Every once in a while, you realize that these abstract, symbolic responses move people in a way that you never dreamed of," he says.

We spoke again with Glaser just prior to his new poster series' launch, and he expanded on the purpose of and impetus behind this batch of designs, whose message, while universal in scope and application, speaks explicitly to the worldview wrought by the Trump presidency and our current political and cultural moment.

You say in your Hall of Fame video that one of the initial purposes of the subway posters was to elevate the idea of the institution, and to show that "we're not like everybody else." What is different about SVA and how do these posters convey that?

One thing that they say is that the school stands for quality—but of course, everybody hopes that. As advertising there's very little you can say which people are not cynical about, which is appropriate. So the question is, at this point in its history, what is it you can say that people believe? That is the most difficult thing now, in terms of communication. What you do [and what the College did], is assign first-class people who were considered to be the best in their field and give them an assignment that demonstrates the quality of what they do and what the school is committed to. They're obviously committed to high-level graphic arts, because the people who are most conscious of that are actually doing works that the people in the subways are seeing. Any representation that says we stand for quality has to be convincing of that quality, so the evidence of your position is the work itself.

More generally speaking, what do these new posters say about the role of an art school? Of an artist?

I have an objective with these three posters—although it was implicit in all the other earlier posters—that is, the role of design and art are basically roles that also include social engagement. Not only personal vision or personal talent or personal insight or genius but also an activity that makes people feel that they are involved in something together. It's kind of the counterpoint to Trumpism, which is "me for me," and it's a sense that we're part of a larger system, humanity itself. These posters [go] one step further as the threat to that idea becomes more evident with Trumpism.

You cannot say things directly in communication, you have to be oblique or enter into people's consciousness sideways. So the first one, Give Help. That one is an attack on that which is becoming increasingly clear: Trump's real contempt for Puerto Rico, or for people of color, and for anybody in trouble who isn't white and rich. This poster—a submerged home, and a beautiful quote by Oscar Wilde, conveys that kindness is worth more than the grandest intention. We've got to deliver on our promise to help our fellow Americans.

Next, To Dream Is Human. That's a bit of an abstraction, but it applies to something quite specific—Trump's attitude towards immigrants. He refers to them contemptuously as Dreamers and to [their] deportation, that we may throw them out of this country. My attempt here is to transform the worddream, which is used pejoratively by Trump, into an aspirational word. To dream is human; the most, perhaps, important aspect of humankind is the ability to dream.

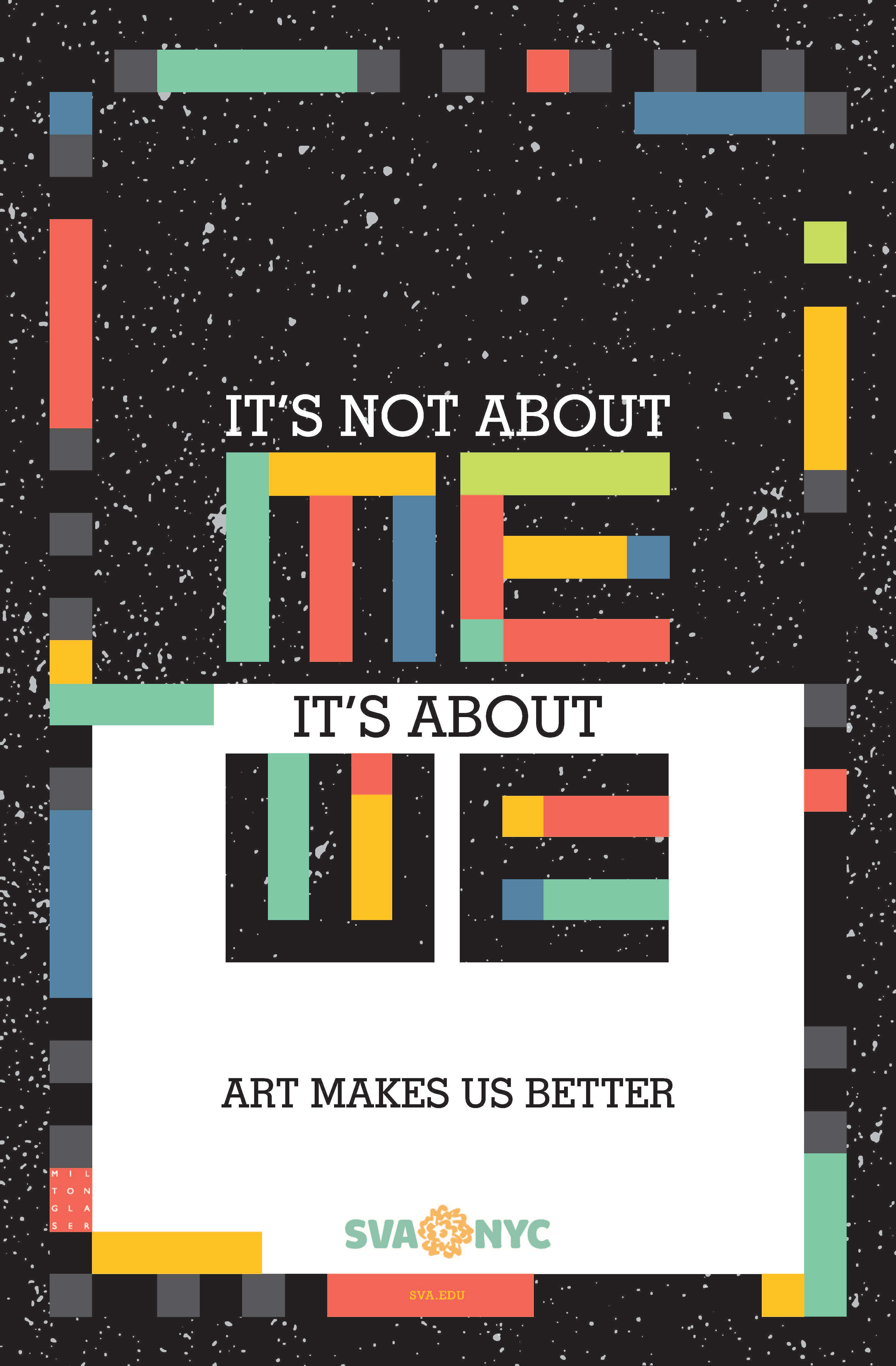

And then finally, It's Not About Me, It's About We. All art ultimately is about collective experience, and "art makes us better" is a reality that I truly believe in. It is the [antidote to] the narcissism and selfishness that exists in human nature. So [this] is a direct reflection of Trump's attitude toward the world, where everything is about him. Again it's an attack on this narcissistic, selfish atmosphere that Trump has managed to create. This is an attempt to compensate for that. In the way that art appeals to the most generous part of the human spirit, this is an attack on the most selfish parts of the human spirit.

Clearly your work is often shaped by or acts as a response to the political situation, but after a record 24 subway posters for the College, where do you turn to for ideas? Visually speaking, where are these new designs coming from?

All these jobs are divided between the sensate and the logical. My logical path is to attack the assumptions that Trump has purveyed—propaganda, essentially. We have seen how susceptible people are to repetition. You attach an adjective to any word and you bend the word. And Trump [has been] a bit of a genius by planting things in people's brains and saying them over and over again until they can no longer tell the difference between what is truth and what is not. The logical [path] is to substitute other ideas and other words for what Trump has planted in our brain.

The other [path] has to do with form and the mystery of beauty and the mystery of art—which is we don't know what these images come from, we don't know where color comes from, we don't know, for instance, about shapes and typography and so on. These are in the realm of intuition and artistic skill, whatever that means. It sounds superficial but it's ultimately the only thing you have to depend on once you get past the logic of things, and logic is not as powerful as intuition.

Has your approach to the subway posters and designing for the College changed over the years?

[Yes], as everyone who is open-minded aspires to. You see a lot of work that, because it is commercially acceptable, becomes a pattern for repetition. That history of success, which is commercially desirable, is also personally damaging. You've not [had] to examine each situation as new or potential; you basically say, what have I done in the past, that works in some form. Of course inevitably that's a characteristic of everybody who works, but you must recognize the danger in doing that.

I use pieces from my history all the time, at random, but I don't feel [a need] to use what has succeeded just because it has succeeded, because work placed in another context doesn't adapt to the uniqueness of that context. I've basically avoided the question of style in my life because I realized that any form is subject to change as the times change. In some ways these last three are more abstract, and more simple-minded than a lot of earlier things. They are less narrative, less storytelling, and more dealing with abstractions.

In the video, you describe goodwill and doubt as two key characteristics of a good designer. Can you explain how those qualities serve your work?

Design is frequently used to be persuasive toward some objective that you want [the audience] to move toward, not necessarily one that they want to move to. You have to be very careful about what you do in the role of design, and particularly in advertising, which can be an extremely dangerous form—you see how Trump uses the form of advertising and entertainment as a means to basically improve his [profile] to people. You have to be very careful not to persuade people to do terrible things to themselves.

Art is something else, because in the realm of art you are in the business of goodwill and creating imagery and ideas that unite people and make [them] feel more that they're related to each other than antagonistic towards one another. The two activities, even though they overlap, design and art, they have very different purposes in culture and you have to recognize those differences.

Related post: SVA Subway Series Hall of Fame: Legendary Graphic Designer George Tscherny [Video]

This interview has been condensed and edited.

For more SVA videos, visit sva.edu/videos.