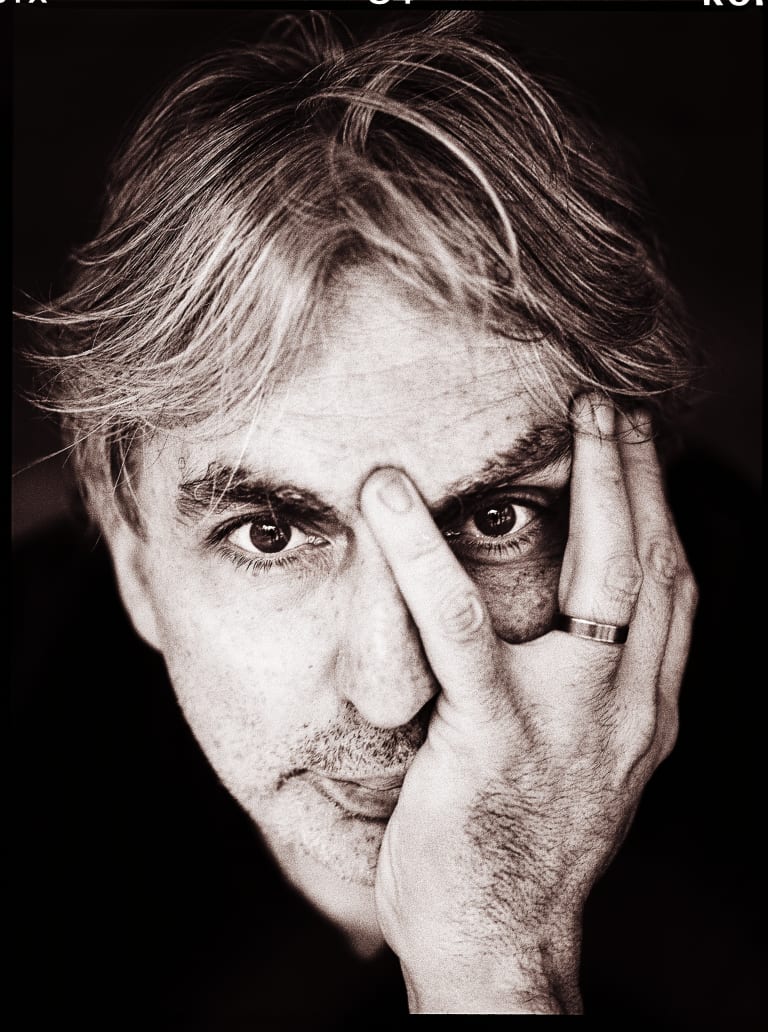

Chris Stein shares his experiences as an SVA student, photographer and musician

Blondie co-founder, photographer and SVA alumnus Chris Stein.

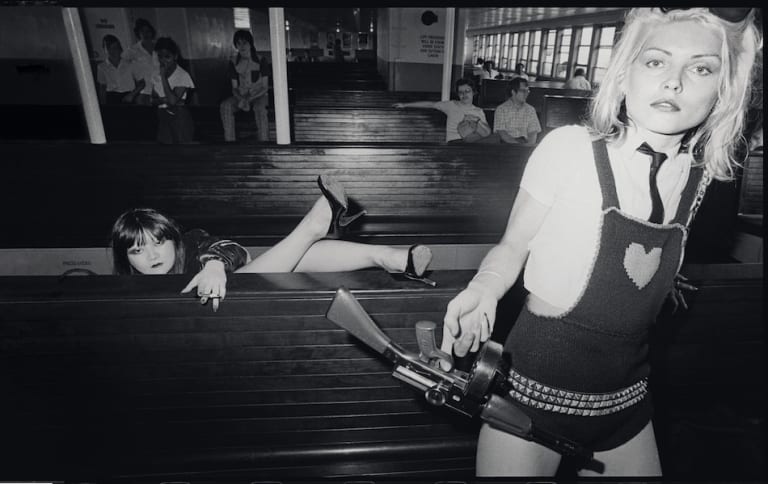

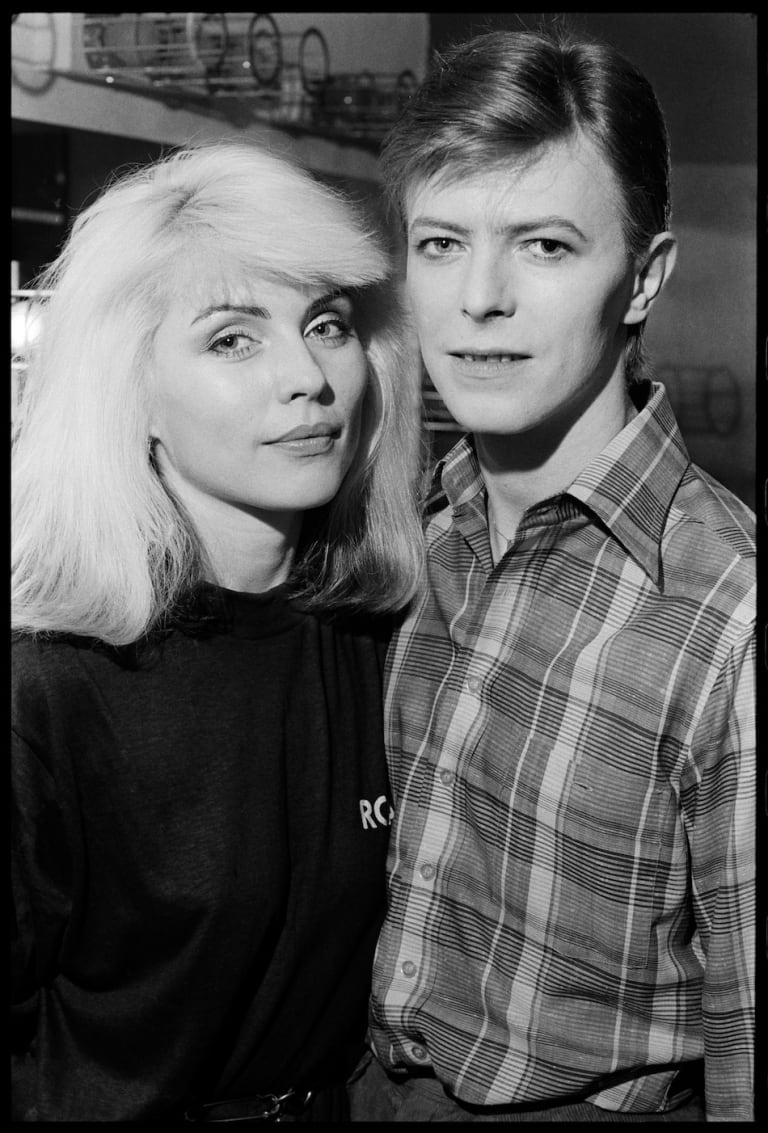

Blondie guitarist Chris Stein (1973 Fine Arts) not only co-wrote, with singer Debbie Harry, enduring, infectious pop songs—such as the shimmering “Heart of Glass” and the New Wave–funk classic “Rapture”—he also documented the band’s vibrant downtown milieu. In iconic portraits, candid shots and video, Stein captured everyone from performers like The Ramones, Richard Hell and Jayne County, to artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, as well as, of course, the astonishingly photogenic Harry—backstage, on set and in hotel rooms around the world. His new monograph Point of View: Me, New York City, and the Punk Scene (Rizzoli) is a love letter to his city, focusing on the urban backdrop to his life through wry, poignant, mostly black-and-white street photography. A series of self-portraits around the abandoned buildings at Sheepshead Bay from 1969 to 1970 and images of the smoking Twin Towers and stunned crowds on 9/11 bookend the moody collection. (An earlier collection of Stein’s photos, Chris Stein / Negative: Me, Blondie, and the Advent of Punk was published by Rizzoli in 2014.)

I graduated from SVA a couple of decades after Stein, under the reign of Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, whose embrace of broken-windows policing and crackdown on so-called “quality-of-life” crimes scrubbed the city of graffiti and kneecapped underground nightlife. As I look back, it makes sense that the turn-of-the-century dance-rock and electroclash music scenes in New York—which my own post–riot grrrl band, Le Tigre, floated between—would find inspiration in the aesthetics of the bygone demimonde Stein chronicled. He and I spoke a few days before Christmas 2018 (and a month before his public talk, with Harry, at the SVA Theatre, hosted by SVA Career Development) about art school, Instagram, Brooklyn’s Midwood neighborhood and his new book.

Johanna Fateman: So what do you think about your time in art school now?

Chris Stein: It was great. I have really fond memories of it. It was probably considerably different back then. We used to sit around and smoke pot in the hall behind the cafeteria. My friend Henry Frick, who was very close with Vito Acconci, did really crazy pieces. You know, he called them “pieces.” He set up a galvanized tub in the lobby and for a week he just came and lay in the water naked. Stuff like that was going on regularly.

JF: Yeah, I graduated in 1997 and it wasn’t really like that. At least I don’t think so. I don’t even remember a cafeteria! Who were your teachers?

CS: I had great people, like Alex Hay and Malcolm Morley. I had a lady named Irene Stern as a photo teacher who was great, very inspiring. Bill Tapley and Al Brunelle, who was really into the occult; he was kind of a magician. And I had Mel Bochner, who is still out there in the art world. Oh! And Steve Reich! I had a synthesizer class with him.

JF: Wow. I would have been into that. So my bandmates went to art school, too—they studied photography and film—and I do think our backgrounds in visual art really formed what we did as a band.

CS: Yeah, sure, John Lennon and Talking Heads, all these people came from art-school backgrounds.

JF: Well, being in a band and performing is visual in the obvious ways. But I think in Le Tigre we were really interested in appropriation, the ideas and politics around it, and we were influenced by the conceptual and photography-based work of the ’80s and beyond. In music, that interest translated into digital sampling. I guess what I’m getting at is: Do you feel like there is a relationship between how you approached photography and music?

CS: I think music and visual stuff use different parts of my brain. I don’t know. When I was in SVA it was really the kickoff of the conceptual-art period. Which was great, but I was much more of a romantic. So though I was a fine-arts major, I drifted into photography. And I was always aware how much photography influenced music. You know, when I saw pictures of bands I admired as a kid, I knew the image was a major component. And then I started seeing the New York Dolls perform and I started meeting people in the music scene. My last year, my senior year, the guys from the Magic Tramps, who I was then friends with, I got them to play at an SVA party. I don’t know who the hell remembers that. The Magic Tramps are pretty obscure.

JF: So you graduated and got more seriously into music. Did you manage to avoid ever getting a real job?

CS: I never had a real job! I painted a bathroom with Bill Tapley, who is still a working artist, very into color theory. He was a great teacher. I actually emailed him a few years ago—he’s a very inspiring guy. Anyway, he was working on Bert Stern’s little clubhouse uptown—whatever you want to call it—and I painted the bathroom up there. Bill was all about color effects, gradations and complementary colors and stuff like that. So the bathroom was really bright orange and the rest of the place was blue. Apparently I didn’t do a good job and he had to touch it up. That’s probably the closest I ever had to a job.

JF: Looking through your two books, it seems like you must have always had a camera with you. My dad grew up in Midwood, Brooklyn, too, and as a kid in the ’70s and ’80s, I visited some of the neighborhoods in your images. It’s kind of shocking how much everything has changed.

CS: Really? Where did your dad live?

JF: The Avenue N stop on the F line.

CS: Yeah I lived on Avenue K, J, right around there.

JF: Do you still go out there?

CS: It’s very different—all Orthodox and Hasidic now.

JF: Yeah, I know. My grandparents were Jewish, but, you know, secular, socialist.

CS: Yeah, my parents, same thing. I went to the same school as Woody Allen. He went to Midwood High School. It's difficult with him, because I’m sympathetic to the movies.

JF: It’s a bummer. But there are other neighborhood luminaries. Roz Chast went to Midwood, too. I think around the same time as you.

CS: Wait, who’s that again?

JF: The New Yorker cartoonist. She also really captures a New York Jewish neurotic reality. . . . Getting back to your photography, I wanted to ask how it worked for you to have this equipment and to shoot on tour. I think touring can be exhausting socially, meeting people all the time. I imagine it might be easier to have something to do—like take pictures. Or set up that unwieldy video rig!

CS: The video stuff was really heavy, kind of insane. I guess I did it for fun. I didn’t think about it too much. I don’t know if I was emulating Andy [Warhol], who I always saw recording everything all the time. But that was probably in the mix. The question I always get is: How aware was I of the significance of what I was recording? There were a couple of moments that were over the top, and I recognized the historical implications a little bit. Like when Blondie did an appearance in London at a record store and the traffic stopped and thousands of kids showed up. . . . Mostly, I was just in the moment. I still have about eight hours of footage I haven’t done anything with.

JF: While looking for you on Instagram, I could see that Blondie-mania is going strong. People would love to see the video you shot!

CS: Yeah, we get a lot of love as the elder statesmen. And we’re figuring out what to do with that video stuff.

JF: With Instagram, did that feel like an easy thing, to go totally digital and to use this new platform?

CS: Yeah, you know, film is like vinyl. It’s kind of a fetish. And I don’t care about that. Digital stuff is so much easier to deal with, for photography especially. So I love Instagram. There are so many great street photographers posting there. That was part of the impetus of the book, you know, seeing all this really great work by people like Clay Benskin—he’s been written up in the Times and stuff. Another guy named Matt Weber. I’ve hung out with them.

JF: I think your street photography might be a surprise to some people. You’re so associated with punk and Blondie, et cetera. But I love how all the material is united by the storytelling element. It makes it so much richer to have the text recollections, in your own voice, accompanying the images.

CS: All of the photos trigger memories. People come up to me frequently and tell me about some event or something that I was a part of that I don’t remember at all. But when I have the image in front of me it’s a whole different thing; I remember. Both Tom Verlaine and Richard Hell have told me that I auditioned for Television, which I don’t remember at all, but I’m polite and I tell them I remember it.

JF: They, like, bring it up decades later just to reiterate that you didn’t make the cut?

CS: Well, Richard—he’s a great writer—in his books, just says I was too nice. They wanted someone who was crankier.

JF: You don’t seem very cranky. It was really nice talking to you.

CS: You, too!

This conversation has been condensed and edited.

Johanna Fateman (BFA 1997 Fine Arts) is a writer, musician and owner of the Seagull Salon in New York City. She regularly contributes to Artforum and The New Yorker.

A version of this article appears in the spring 2019 Visual Arts Journal.