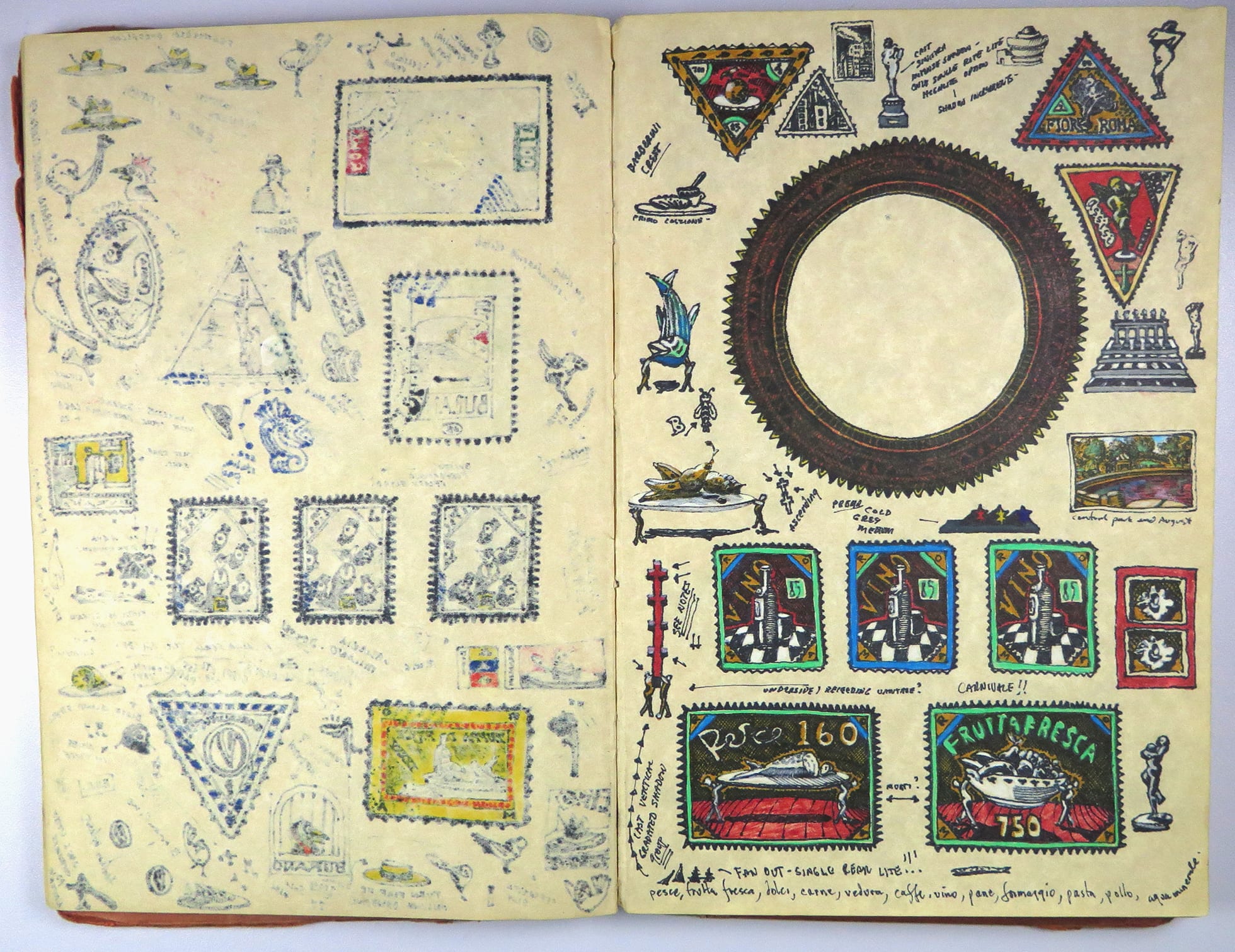

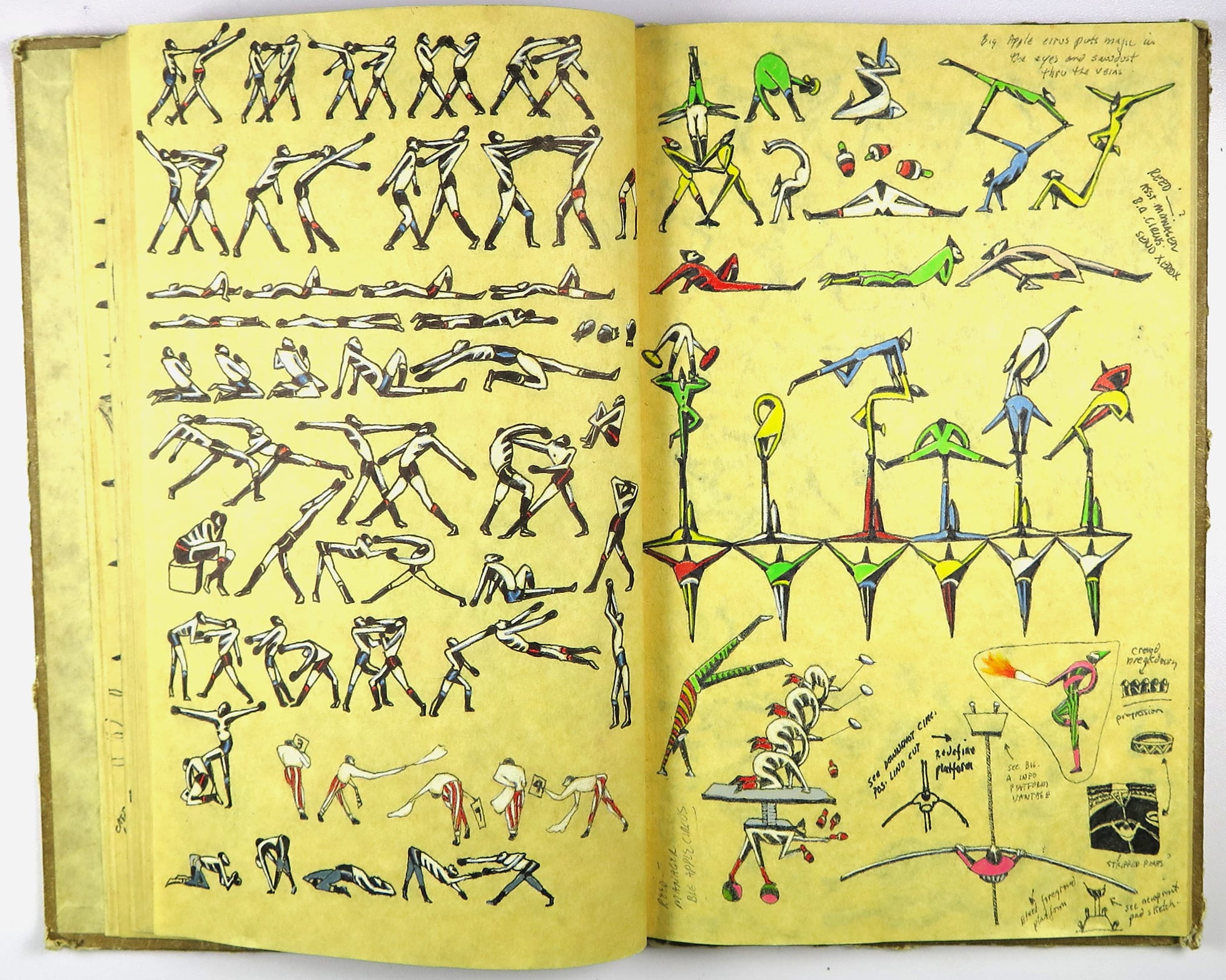

A selection from one of artist and alumnus Carl Titolo's sketchbooks, courtesy the artist. Titolo, who teaches in SVA's BFA Design and MFA Illustration as Visual Essay programs, has been keeping sketchbooks, scrapbooks and journals as part of his art practice for more than 50 years.

If you were to open a flat-file drawer in the Manhattan studio of Carl Titolo (G 1967), you should pull up a chair—you’re probably going to want to stay a while. The drawers are filled with layer upon layer of sketchbooks; each opens to a spread carpeted with minute, jewel-toned paintings, delicate pen drawings and jottings about art, food and architecture. Titolo calls these sketchbooks, which he has been keeping for more than 50 years, "appetizers." For any visually minded person, they amount to a feast.

The appeal of sketchbooks is long-lived, but arguably it has gained a new dimension these days, ruled by images and image-sharing. The ephemeral quality of sketches pairs well with that of social media, which could account for the more than 21 million Instagram posts currently tagged "sketchbook." At the same time, it seems likely that some of the recent appreciation for sketching stems from its embodiment of two qualities that are scarce online: tactility and privacy.

Three SVA alumni agreed to speak with Visual Arts Journal about the role sketching plays for them. Titolo is an artist, illustrator, and longtime faculty member in the College’s BFA Design and MFA Illustration as Visual Essay departments. Kara Rooney (MFA 2009 Art Writing) has an interdisciplinary practice that encompasses performance, sculpture, and criticism; she also teaches art history at SVA. Frank Ockenfels 3 (BFA 1983 Photography), who is based in Los Angeles, is an in-demand photographer known for his iconic portraits of celebrities such as David Bowie and Angelina Jolie. These artists' generations, backgrounds and practices are greatly divergent, but for all three, the reasons they sketch are deeply entwined with the way they approach and produce their work.

For Ockenfels, his notebooks started as "technical journals," with Polaroids and diagrams showing how he planned to light a photograph. Then, as he recalls, "I found myself collaging the extra Polaroids and scraps of paper related to the shoot. Then I would write down my thoughts or opinions on the shoot—a great way to clear my head." His notebooks are still an excellent tool for head clearing, he notes, but they have now evolved into something far more complex, blending handwriting, expressive ink drawings, and "cheap printouts of my work, old and new." Many of the resulting entries are layered and densely textured, and their content is often filled with sexuality and an intensity of emotion. "I like to make things that feel raw, real—that feel 'one of one,'" he says.

Kara Rooney also brings layering and collage into her sketches, energetic sweeps of black on white, often woven through with snippets of her own photography. Rooney makes these pieces in series of four or five, standing up at a table and working with inks, graphite and water-based washes on heavy white paper. She calls such works "warm-ups," a name that brings to mind her time as a dancer, though she says they really stem from her training as a painter. "Particularly when I'm between projects, or when I'm beginning a body of work, they're a way for me to get into gestural mindset of the sculptural forms," she says. "Even though I work with a lot of theory, this particular physicality has to be there first." In a manner similar to Ockenfels, Rooney's sketches bring together different strands of her practice. For a series of works that she calls "Reverbs," she photographs her sculptures, manipulates them in Photoshop and then incorporates them in three-dimensional pieces. Printed-out test images that that didn't make it into the finished works later have their use in the warm-ups.

Rooney also keeps notebooks, mostly devoted to writing, and they are sprinkled with imagery. "They're more like idea journals," she says, explaining that on any given day she might be writing "something that could become an artist’s statement" or recording "an experience that would go into the work."

Kara Rooney,

warm-ups

, ongoing, acrylic ink, digital photography, graphite, pen, charcoal and paper. Courtesy the artist.

Even more than Rooney, Carl Titolo sees his sketchbooks as a source for his finished work. "They are a springboard for everything that matters," he says. "It's pretty much gathering ingredients, and since I always have a pad with me, I'm always drawing." It's a habit that started early. As a young artist right out of SVA without a studio of his own, he would often draw from observation while sitting in places like Horn and Hardart automats—restaurants in which patrons could retrieve their meals from cubbies with glass doors. Sketches like these got him his first editorial job, when Penthouse magazine featured his drawings as a visual essay along with a poem written by a friend. Over time, Titolo continued to sketch his surroundings, but became focused more on small details—a door knocker, a cup of espresso, fishing boats propped against a wall—that he observed and collected from his daily life and travels. He and his wife have made regular journeys to Italy since 1980, and both his notebooks and finished work reflect his love for that country. These days, at home in Manhattan, he makes notes in his sketchbooks at a café while drinking his morning coffee, then often heads to his studio to work on a series that evokes Italian locales.

Echoing Ockenfels, Titolo describes the sketchbook practice as a way to clear one's mind. "It can take you anywhere your imagination wants to take you," he says. "It's a form of therapy." For years he has used sketchbooks in his curriculum, giving all of his students a pad at the beginning of each semester. He allows them freedom to do what they want in the books, a freedom that, he says, "has produced, unanimously, the most creative work from every single student that they've done in any other form."

SVA Features asset

To celebrate the enduring popularity of sketchbooks as a tool for artists of all types, SVA is introducing a series of short videos spotlighting the creative journals of its students, faculty and alumni. First up is Carl Titolo (G 1967), an artist, illustrator and longtime SVA faculty member. For more, visit SVA's YouTube channel.

Having a place to work where there is no agenda is key to the important function sketchbooks serve for students and established artists alike. "My journals answer no question nor have any need to be understood, they just express random thoughts or the visual vomit that's in my head," Ockenfels says. "I can look at a blank page and not be afraid or put too much weight on that first line. I like seeing the scissor marks on the paper or the tear, the imperfection of the ink and how it stains the paper and moves without control across the surface of the page. To spatter ink across a piece is so freeing because you can only guess where it's going to land."

"Visual thinking" like this goes beyond a diary, capturing more than just articulated thought. "[Sketchbooks] become ... a magical history of your head and your hand," Titolo says. Rooney says she will often go back to her journals to see where her thinking was six months previously: "[They're] an archive of my daily existence as an artist, and an incredibly valuable part of my working process."

They are also very personal. As Rooney says, artists' journals "can give you insight not only into the working process but into artists' lives and reflections." That's one reason we like to look at sketchbooks, and it is also the reason that there will always be a tension between that desire and the need for artists to keep them private. When Ockenfels, Rooney and Titolo share their sketches, they let us behind the scenes of their work, giving us a glimpse into something not created for the public eye. As Ockenfels puts it, when people ask to see his journals, "A few will start to ask questions or have ideas about what works or doesn't work. With a smile on my face I tell them I don't care and I'm not interested. They are for me."

A selection from one of Carl Titolo's sketchbooks, courtesy the artist.

Caitlin Dover is a writer and editor based in New York City. She has worked as managing editor of Print and has written about design and culture for Print, Metropolis and ELLE Décor, among other publications.

A version of this article appears in the fall 2017 issue of Visual Arts Journal.