SVA Features asset

This fall, the MFA Computer Art Department at SVA is celebrating its 30th anniversary. Launched in 1986, the graduate program—the first in its field—now claims more than 1,100 artists, animators, designers and programmers as alumni. These alumni have gone on to direct and animate award-winning films, create innovative works of digital art, and more.

To commemorate this milestone, MFA Computer Art is presenting an exhibition of alumni work—on view from Saturday, October 22, through the end of November at the SVA Flatiron Gallery and Flatiron Project Space, with a reception on October 28 at the MFA Computer Art Lab, all at 133/141 West 21st Street. The department is also producing a video documentary on some of the program’s more notable graduates; it premieres December 1 at mfaca.sva.edu, and the trailer appears above.

To further mark this anniversary, and to demonstrate the breadth of achievement of the department’s alumni, we asked eight MFA Computer Art graduates to select and talk about one of their favorite works. The results are presented here, and in the fall 2016 issue of

Visual Arts Journal

, the College's alumni magazine.

Nakyung Lee (2016)‘Nowhere.’ (No Where, Now Here), 2016, performance with digital art and sound.

‘Nowhere.’ (No Where, Now Here), the thesis project by 2016 Alumni Scholarship Award recipient Nakyung Lee—who attended SVA after studying fashion design in her home country of South Korea—combines new media and performance art to explore Eastern and Western concepts of suffering as intrinsic to the human experience and a path to inner peace. But despite the weighty philosophical aspects of the material, Lee says, “the technical part was the hardest thing for me to figure out.”

She began by composing an electronic score containing seven instrumental layers, and drawing a series of images inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy (skulls, flames) and Buddhist thought (mandalas). Cian Rou Chen, a friend and fellow student in the program, rendered those drawings in 3D, and Lee employed additional software to apply effects to the images based on the sounds in her score; for example, low-frequency sounds make the images shake, while high-frequency ones distort them. In addition, Lee enlisted the help of the South Korean dancer and choreographer Youngeun Kim to create a series of gestures that represented Dante’s famous journey through purgatory and hell while at the same time reflecting aspects of Buddhist thought.

To create the piece, a dancer performs Kim’s choreography to Lee’s soundtrack as the images are projected against a white wall, while Lee herself makes adjustments to the visuals in real time. Having presented it as part of the MFA Computer Art class of 2016’s thesis presentations last spring, Lee is currently submitting

‘Nowhere.’

to arts festivals.

Kamil Nawratil (2013)Perception of Consequence, 2013, multimedia installation.

SVA Features asset

Kamil Nawratil’s interactive new-media piece Perception of Consequence (which was also his MFA thesis project) grew out of a philosophical argument he had with a friend—a fitting origin, since the principal “characters” in the work, a pair of blobby animated creatures composed of a mysterious fluid, seem at times to be locked in conflict.

The argument was a heady one—“one of those debates you have when you’re 19 or 20,” Nawratil says—and concerned self-organized systems, a topic of particular interest to the artist (the name of his studio, VolvoxLabs, refers to a type of unicellular algae that forms large, freshwater colonies). Inspired, he set out to create a piece in which shapes that were bound by the rules of physics moved from order to chaos and back again—a journey that could represent the physical state of a bunch of molecules or, more abstractly, the emotions of two people in a relationship.

Nawratil created the basic animations using one particular piece of software, then used another to ensure that the movements of the shapes’ water-like matter were physically realistic, and rendered the results in 3D. The resulting work is projected onto a custom-built wooden structure, the wavelike shape of which visually echoes the free-flowing quality of the images playing across it. An electronic score accompanies the piece in surround sound, and is synced to the animation by a computer program that also controls a pair of fans. The fans’ wind speed and direction coordinate with the movements in the video, adding a tactile element. Nawratil has mounted Perceptions at Copenhagen’s Re-new digital arts festival and at the 2013 SIGGRAPH Asia Art Gallery in Hong Kong.

Today, VolvoxLabs specializes in providing these kinds of immersive, multimedia experiences for clients such as

American Express

,

Samsung

and superstar chef

Ferran Adrià

, blending visual effects with physical fabrication and sound. “We’ll work with anything we need for a particular project,” Nawratil says.

Jennifer Yiu-Chen Yang (2012)After-effects art for Marco Brambilla’s Apollo XVIII, 2015, multimedia installation in Times Square.

SVA Features asset

Jennifer Yiu-Chen Yang is accustomed to working big for her motion graphics work, which often combines abstract shapes with figurative imagery. After graduating from SVA, a fellow alumnus recommended Yang for a job creating video animations for Beyoncé’s live shows, including such high-profile outings as the entertainer’s 2013 – 2014 Mrs. Carter tour, 2014 On The Run Tour (with her husband, rapper Jay-Z) and 2016 Formation World Tour, as well as her acclaimed performance of “Crazy in Love” at last year’s Budweiser Made in America festival.

Yang’s work for Beyoncé combines art projected onstage, to synchronize with the live choreography, and motion graphics displayed on multiple LED screens arrayed behind the singer and her ensemble.

Similarly, it was a Beyoncé-affiliated director who recommended Yang to video and installation artist Marco Brambilla, who had been commissioned to create a work for Times Square Arts’ Midnight Moment, an ongoing effort by the New York landmark’s sign operators to screen custom-created, technically innovative content every night on more than 20 electronic billboards and kiosk screens in the square.

Brambilla conceived his Midnight Moment project, Apollo XVIII, as an imaginary moon shot—a virtual version of a planned 1970s mission to the moon that NASA never got around to launching. Yang’s role was to fit Brambilla’s vision into the many differently shaped screens. After experimenting with various approaches to composition and storytelling, she ultimately deployed a combination of real, archival NASA footage and computer-generated animation onto the “canvas” of electronic signs placed around the square in a way that gave spectators the feeling they were witnessing an actual launch of a Saturn V rocket.

“It was a challenging project,” Yang says. “But nothing can compare to the moment when I saw all of that hard work shown in Times Square.”

Dustin Grella (2009)"Animation Hotline," 2011 – present, online animations.

SVA Features asset

In 2011, Dustin Grella, an animator and documentary filmmaker, was busy touring festivals with his thesis work, the animated short Prayers for Peace (2009). He found that he was not, however, making anything new. So he enlisted his old SVA instructors to help circulate a telephone number for which he’d set up a voicemail account; he then created brief animations based on the messages that strangers left. After posting his initial efforts to Vimeo and Facebook, the project took off, and Grella has since produced some 200 shorts—all clocking in at around a minute or less—for what he calls his "Animation Hotline" series.

To create videos for the series, Grella and the team at his Bronx-based operation, Dusty Studio, photograph individual drawings, made with chalk on slate, that illustrate the story told on a voicemail message. The images are then digitized, edited and strung together, producing films that unspool at 12 frames per second. Lately, Grella has been experimenting with animating paper cutouts and paintings. (“If your work isn’t evolving and changing, it gets stale,” he says.) But the films themselves remain intimate vignettes from individual lives—like Ticket (2011) (above), Grella’s personal favorite, in which a homeless woman tells the story of being invited to attend the theater for the first time.

Grella continues to collect stories for the series, which he distributes himself via the Dusty Studio’s website and through various social media platforms. (He also occasionally sets up booths at events like Sundance and the Hamburg Short Film Festival, creating brief animations on the spot.) But he hopes “Animation Hotline” gets picked up by an established distributor that could provide an online home for regularly scheduled releases, like a webisode series “or a comic strip,” he says.

To watch select “Animation Hotline” shorts, visit dustystudio.com/animation-hotline. To leave a message on the hotline, call 212.683.2490.

Federico Muelas (2002)Blue Flower/Flor Azul, 2012, permanent public art installation.

SVA Features asset

Blue Flower/Flor Azul has deep roots.

Installed on one side of George Pearl Hall, home of the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, the multimedia work by Federico Muelas—a new-media artist and faculty member in SVA’s BFA and MFA computer art departments—is based on his thesis project, Dripping Sounds (2002), which used light sensors to generate electronic sounds based on images of ink dripping into water. In fact, the building’s architect specifically requested something similar to Dripping Sounds when he commissioned Muelas to make the work. But when he got the assignment, Muelas says, the technology for an expanded version—in particular, the material for a large, energy-efficient screen that would be clearly visible in daylight and the circuitry required to control it—“didn’t yet exist.” It took Muelas and 30 collaborators from across the United States, Australia, and England four years to develop it.

Blue Flower/Flor Azul employs a 900-square-foot screen composed of 3,740 pixels made from low-power LCD film, along with a graphics card—a circuit board that generates imagery—that Muelas and his team designed. When electrified, the pixels act as mirrors, reflecting whatever is in front of them: the sky, the city, passersby. When turned off, the pixels are white. During the day, the screen displays animations that silhouette the ever-changing forms of blue ink as it diffuses in a volume of water, the ink appearing in white. At night, all the pixels are turned off and nearby projectors cast full-color video of the ink onto the screen.

Day and night, speakers broadcast a soundtrack that corresponds to, and indeed is generated by, the images being displayed on screen. To create the sounds, Muelas used sensors to measure the intensity of light passing through the ink, and employed computer software to convert those shifting intensities into musical notes. For Muelas, it’s all part of his ongoing effort to use art “to understand how nature behaves.”

Andy Deck (1993)Crow_Sourcing, 2012 – present, software, data, and web, installation and print media.

As a media artist and writer, Andy Deck has long been interested in environmental themes such as extinctions and global warming. So when Turbulence, a nonprofit organization dedicated to commissioning Internet art, asked him to create a piece involving social media, he decided to use the opportunity to attempt to get human beings to think more about other species.

For nearly five years, Deck has been tweeting well-known expressions involving animals (“as the crow flies,” “take the bull by the horns”) from the Twitter account @crow_sourcing, and inviting people to visit a Turbulence-hosted website featuring silhouettes of the animals, where they can add and annotate their own related sayings. (The site can be seen at artcontext.net/crow_src.) Hence the title, Crow_Sourcing: the work uses crowdsourcing to collect and comment on idioms and ideas related to animals.

For an interactive physical version of the piece that was shown at the Furtherfield Gallery in London in October 2012, Deck added barcodes to the silhouettes, printed them on cards and hung them on a wall nearby. (The work was later mounted at the Shot Tower Gallery in Columbus, Ohio, as well.) Visitors called up the animals’ related idioms on a tablet computer by scanning the barcodes and were invited to write additions directly on the gallery wall.

Now Deck is in the process of transforming

Crow_Sourcing

into a book—though given the hundreds of contributions he’s received from around the world, his goal of sticking to one page per animal is proving to be a challenge.

Nancy Kato (1991)Character animations for Dory, Finding Dory, 2016.

SVA Features asset

In the 16 years she has been with Pixar, Nancy Kato has worked on nearly every feature the animation studio has made—including Finding Nemo, to which this summer’s hit Finding Dory was the sequel. By the time Kato sets to work animating a character like Dory, much of the groundwork has already been laid: the script has been written, the voice actors have recorded their dialogue, and even the camera angles have been laid out. But the character herself has not yet come to life. “We know what’s supposed to happen,” says “But we don’t yet have the ‘acting.’” As a character animator, it’s Kato’s job to provide precisely that. “We’re like the actors behind the camera,” she says.

With a static digital 3D model of her character as her guide, Kato begins the animation process by filming herself as she experiments with different gestures and facial expressions. Once she has an idea of how her assigned character should move and react to her scene partners (in the case of the scene shown above, it’s an octopus named Hank), she roughs out a sequence with animation software using simple geometric shapes. Only once the results meet with her satisfaction will she then painstakingly craft a more fluid and fully realized version.

Her colleagues in lighting and effects add further touches, such as realistic shadows and bubbles. When all that’s done, the postproduction crew renders the high-resolution version of the movie that will ultimately appear in a theater near you.

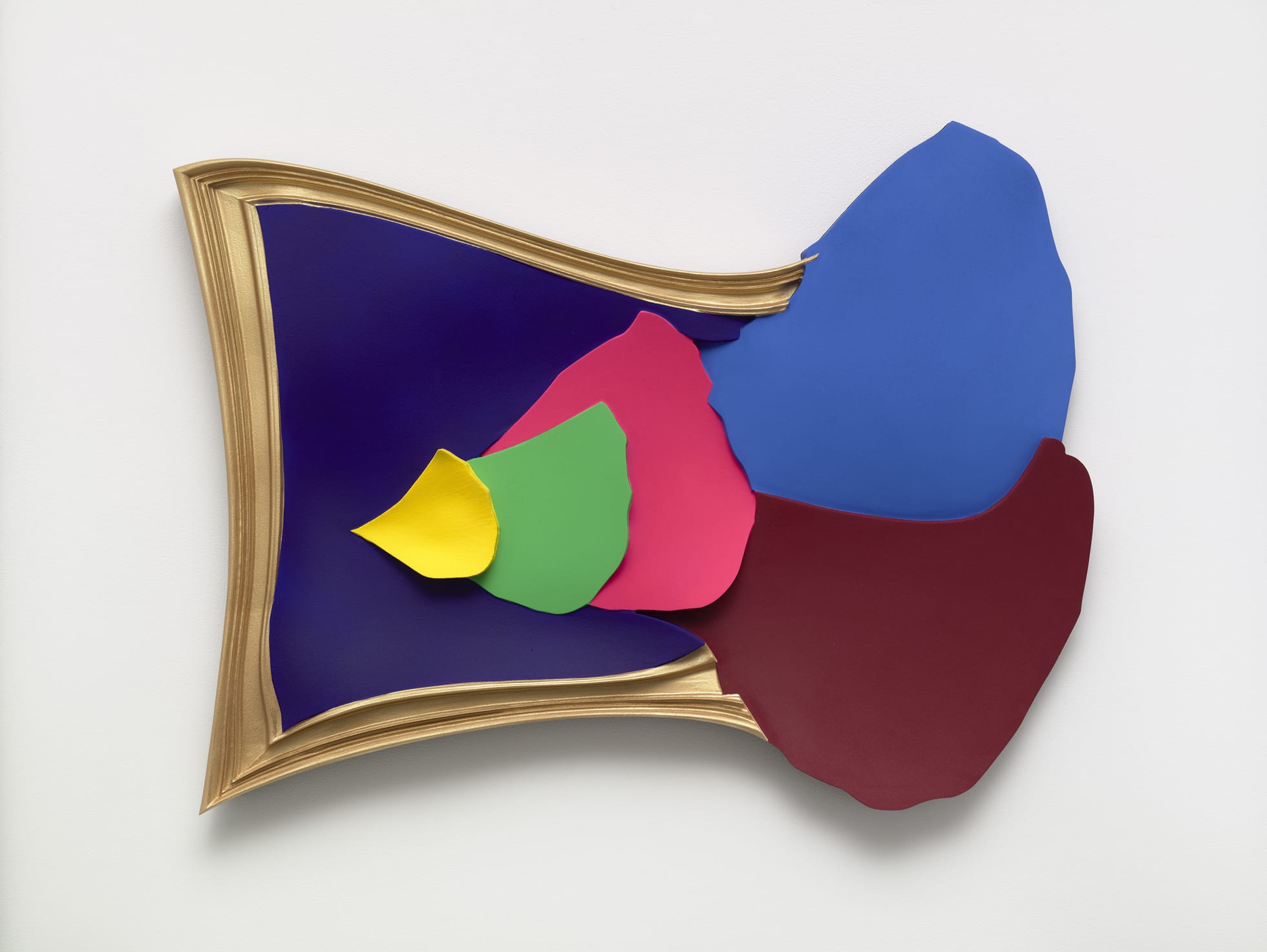

John F. Simon (1989)Expanded Palette, 2016, high-density urethane, medium-density fiberboard, Flashe and acrylic.

Expanded Palette is a wall-mounted sculpture that emerged from artist John Simon’s daily drawing practice, a meditation-like exercise in improvised sketching that has provided the fodder for all of his recent work. (His book on the subject, 33 Practices at the Crossroads of Art and Meditation, is due out November 1 from Parallax Press.) The composition on which Palette was based belongs to a group of what Simon calls his “expansion drawings,” which symbolically represent the breaking of limits—whether of color and form, or of our planet’s natural resources. Trained as both an artist and a geologist, he has long been sensitive to environmental issues.

Simon himself has been pushing boundaries—those of computer-assisted art—for a long time. A pioneer of software art, he taught himself to write code in the early days of PCs, created his own animated drawing tools, transformed desktop computers into works of art that used algorithms of his own design to generate ever-changing images, and eventually moved into fabrication, writing programs to control laser cutters and automated routers in order to produce pieces like this one.

For

Expanded Palette

, the artist scanned his original drawing, converted it into a 3D shape on his computer, and then fed that shape to the automated router in his studio. The router carved the piece from a two-inch block of high-density urethane, after which Simon sanded and painted it. “It’s all just one piece of material,” he says.

Alexander Gelfand has contributed to The Economist, The New York Times and Wired, among other publications. A version of this article appears in the fall 2016 issue of Visual Arts Journal.