The animator and show-runner talks about his original series and the magic of cartoons

SVA Features asset

Ian Jones-Quartey (BFA 2006 Animation) grew up in Maryland with a librarian for a mother, an engineer for a father and an extended family full of “amazing people to look up to,” he says—including an artist grandmother known for, among other things, designing Ghana's flag. It makes sense, then, that in his animated Cartoon Network series, OK K.O.! Let's Be Heroes, everyone has special powers. Centered on the adventures of K.O., an aspiring superhero who works in a suburban shopping plaza located across the street from a villain’s robot factory, OK K.O.!'s second season premiered this past spring. The first season, which aired in 2017, was released on DVD this past summer. All episodes can be watched at any time on the Cartoon Network app.

Ian Jones-Quartey at the 2018 San Diego Comic Con. Courtesy of Cartoon Network.

After several years spent working on other acclaimed Cartoon Network series, including Adventure Time and Steven Universe, which was created by fellow alumnus Rebecca Sugar (BFA 2009 Animation), Jones-Quartey was invited to pitch ideas of his own to the channel. OK K.O.!, which began production in 2015, was unconventional from the start. Given its action and superhero elements, the network took the unusual step of licensing the property to video-game companies while the show was still in the works. This was an opportunity that Jones-Quartey and his co-producer, Toby Jones, welcomed, as it allowed them to consider the game developers' best ideas as fodder for stories. (To date, two OK K.O.! games have been released: Lakewood Plaza Turbo!, an app by Double Stallion, and Let’s Play Heroes, a console title by Capybara Games.) The pair further opened the collaborative process by organizing two "jam" events— one for the gaming community in Portland, Oregon, and another for animation students in Los Angeles—at which teams were given the setup and characters of the series and encouraged to let their imaginations run wild.Regardless of these outside influences, the basic premise and core inspirations of OK K.O.! remain personal. Sometimes the autobiographical reference is coded—the series title, for example, is a tribute to Jones-Quartey's grandmother, whose name was Theodosia Okoh. Sometimes it's more straightforward: Like K.O., Jones-Quartey worked as a store clerk as a teenager. "OK K.O.! is basically the show I would've wanted to watch as a kid," he says. "Those were the times when I was really getting excited about cartoons and video games and anime and animation, so it all kind of fits together for me. It's a super-cartoony cartoon. It's wacky and expressive and weird."

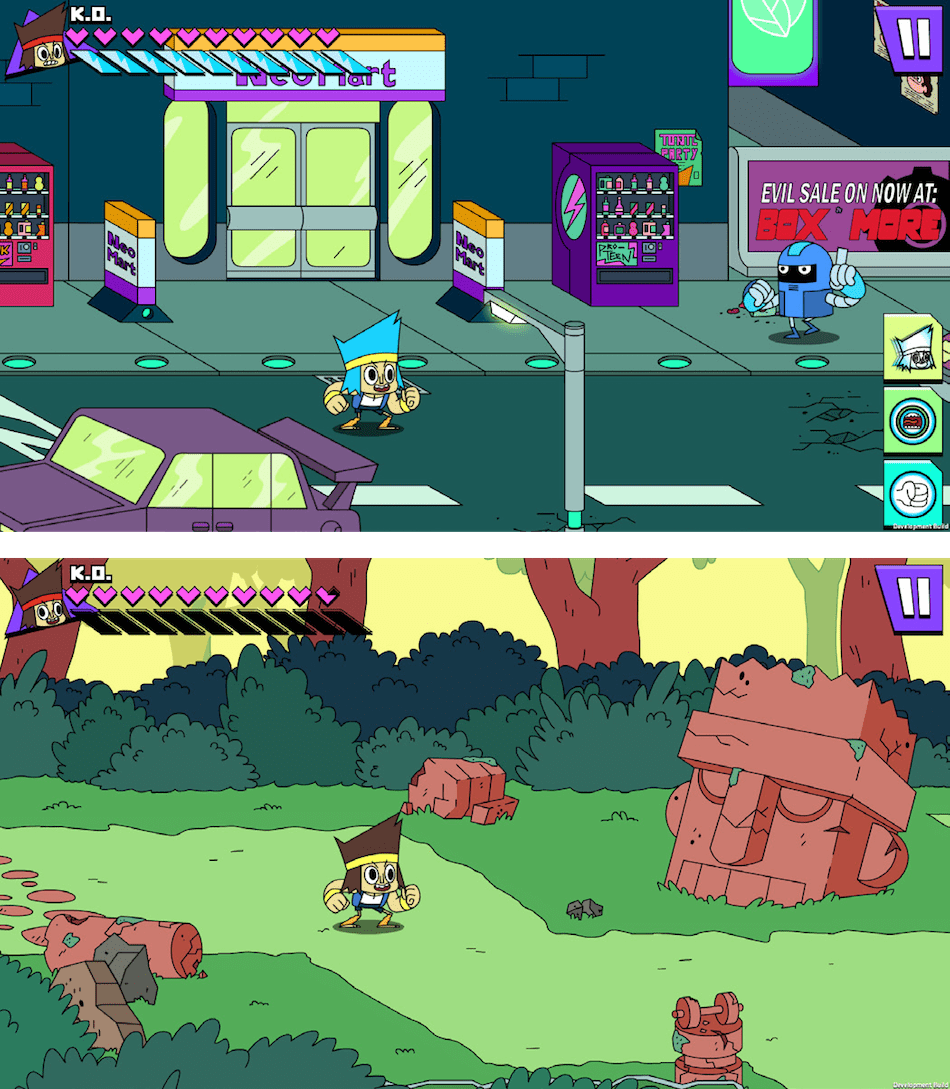

A still from the OK K.O.! Let’s Play Heroes video game. Courtesy of Cartoon Network.

There's a deliberately unfinished quality to the look of OK K.O.!, similar to Beavis and Butt-Head or early Simpsons episodes. Was that an intentional choice?

Yeah! For me, the thing that's most exciting are those early seasons of a show, where you see people coming up with solutions, figuring things out. You see rapid changes in development in the ways the characters are drawn, the style of the show. When you look at Season 1 of The Simpsons, you see a rough product, but it's evolving as you're watching it. Also it's something that I like to look for in a lot of golden-age cartoons, like early Fleischer and Disney cartoons. Seeing that development from short to short, and even within the same cartoon, you see it changing and growing and turning into something better and better. And for me, that's the best. I'm not a fan of when you just lock it down and it becomes a stagnant thing forever. I want to make a show that's constantly changing. When a new person comes in and has something new to add, I want to make sure that I make a home for that. In terms of the line work, I want to make sure that it always feels approachable and at the level of the people watching the show. So if you're a kid, you think, "This kind of just looks like notebook doodles. I draw notebook doodles. Maybe I could do something like this." The show is animated traditionally, so I was able to ask the studios, "Hey, instead of inking all of the lines, could you leave them as pencil lines?" And so they use like a 2B pencil to draw all the frames, and we retain that line and color under it. That's something that's become part of the DNA of the show. What are some of your other visual influences for the series?

My number one inspiration is classic Looney Tunes. The thing about Looney Tunes that's more special than any other cartoon is, you can see the characters thinking. You can see, just from their facial expressions and the way they're moving, what they're thinking in their heads and what they're about to do. That's something that is really special to me. The second would be another Cartoon Network show, Dexter's Laboratory, which, to me, synthesized the best parts of Hanna-Barbera animation and '70s anime, and that's kind of the feel that we're going for a little bit: The animation is not full, it's very deliberately limited. We drop frames, we slide things around, we do zooms. I love efficiency that is still expressive and entertaining.

In an interview with Slate, you talked about how you want every background character in OK K.O.! to have an identity. Can you explain what that means and how you do it?

In an animated show, if there's a crowd in a scene, you see all these rando people in the background. So I was like, "What if there was a show where each one of those rando people was an individual, with their own story and background and hopes and dreams?" And that's what we did. Before the show came out, Toby Jones and I sat down and we came up with about 70 individual background characters—all different, all unique, all with their own styles and colors and personalities and special powers—and gave that to all the creative people on the show and said, "Have fun with it." And the characters started to take on these new lives. For instance, we made Dynamite Watkins—she's kind of like [a cross between] a wrestling announcer and a TV reporter. At the game jam, a team created an entire game where she's interviewing different villains and when she lands a really cutting answer they explode, and we eventually ended up putting that in the show. Eventually that would come to other things, like, "What is her crew like?" And we created side characters for her. So now she has a cameraman whose name is Cam, he has a camera for a head. And that led to all these other characters, and other characters. We now have, I would say, 140 original characters, because we just keep on creating more. It's the sublime factor of having all these characters and different stories, when you have a piece of art that you can imagine existing outside of the product that it is. So when you see an episode and you see all these characters in the background, and you know them as characters, you think, "What is that character up to when the camera's not on them?" We wanted to give the audience that feeling. Speaking of back stories, how did you come to be an animator? You went to college for it, so you must have decided on the career at least by high school.

I fell in love with cartoons when I was, like, four years old. I started making my own animations by myself when I was in elementary school, using flip books, old Mac programs. I eventually made my own comics and web comics and did a lot of stuff in art in high school, but I always knew I wanted to do animation, and I chose SVA because at the time it was the only program where you were just going to learn how animation works the minute you got there. That was very attractive to me, and my experience at SVA was one of the most creative times in my life.

Stills from OK K.O.! Let's Play Heroes by Capybara Games. Courtesy of Cartoon Network.

Can you tell me more about your time as an undergraduate? Were you working on the side?

One of my favorite things about going to SVA was that it was in the city, and I would stay over the summer. My second summer, I just looked up animation studios in New York and cold-called every single one, and I eventually got a job at a small studio doing commercials, interstitials, slot-machine animation. I just wanted to do it, no matter what, and they were still working on paper, which was awesome. So I basically just was freelancing, interning, knocking on any door I could, taking every single opportunity that came across. Eventually I got into television animation, working at, it's a defunct studio now but they were called World Leaders Entertainment, they used to be called Noodlesoup, and they made the show The Venture Bros. I interned there and became the animation director on that show. I kept working there after college, and I heard about this show Adventure Time that was starting at Cartoon Network, which I thought was amazing. I remember showing the pilot to a bunch of people who I worked with and they were like, "What is this?" And I was like, "It's going to be the future, don't worry about it." And eventually I took a test to work for that show, to be a storyboard artist, and I moved out to Los Angeles. To a current student or someone just starting out in animation, a career like yours might seem unattainable. What do you say when an aspiring animator asks for your advice?

If you have an idea, just do your idea. Don't wait for someone to give you permission to make it. The people I see who actually succeed, they can't stop making things, they can't stop drawing. If you're the kind of person where an industry position is the end goal ... the people I see who are like that, when they get that job, the drive bottoms out. Even while I was at SVA, I was writing my own comics on the side, I was making short films, my friends and I were coming up with ideas and pitching them to each other. And we were doing this for the love of creating something. Every day as I'm making this show, I'm relying on knowledge that I got from making my own things by myself. A lot of the characters and stories and animation techniques that I use are things that I had experimented with on my own. Also, if an executive sits down with you and says, "Can you make a show?" You can just sit back in your chair and say, "Well, look at this. I've made so many things already. I know how to make stuff. I'm going to keep making things whether you give me the money to do it or not." That is so much more attractive than someone who's like, "Well, I've never made anything, this is my first idea and I don't know what I'm doing." [Laughs.] You want to be a person who knows what they’re doing. I'm so jealous of kids who are in elementary school and middle school and high school right now. Because when I was a kid, I didn't have Flash, I didn't have the ability to create animation on my desktop the way students do now. There's no excuse not to be making your own stuff.

A still from OK K.O.! Let's Play Heroes by Capybara Games. Courtesy of Cartoon Network.

What is it about animation that made you want to devote yourself to it? Do you still have that same love for it that you did growing up?

Animation is really special. There's something you can get from watching an animated character that you can't get from a real character. If you're a person in the audience and you look on the screen and see a specific actor doing something, you're like, "Well, that's that actor, that's that person." There's a space between you and the character. With animation, because it's a not-real character that is abstracted and not completely human, you can look at that character and say, "Well, that's me," or, "That's my friend." I think that's an innate advantage that animation has. When Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs came out, the rest of the movie industry was scared. They were like, "This will replace us." They understood the actual power that it had. The industry said, "Well, it can have an Oscar, but it can't get a real Oscar. And we'll have Shirley Temple present it, so it's like a kids' thing, not like a real thing." Because they knew there was a lot of potential in this art form. And that's something that, every day, I'm trying to explore. We're trying to come up with new expressions, new cartoon language for emotions and actions that maybe haven't been represented on screen. I think that's something that only animation can do, and that's the real reason why I do it.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

A version of this article appears in the fall 2018 issue of the Visual Arts Journal.

For more information on SVA's BFA Animation program, click here.