On a nondescript street in Saugerties, New York, two priceless stores of art sit side by side. The first, occupying a squat, anonymous-looking warehouse, is the East Coast facility of Archive Fine Art, which holds artworks for collectors, galleries and museums. The second, occupying a rear unit in the back of a small brick apartment building, is the home of Joe Sinnott (G 1952), a comics illustrator and inker well into the seventh decade of a staggeringly prolific career.

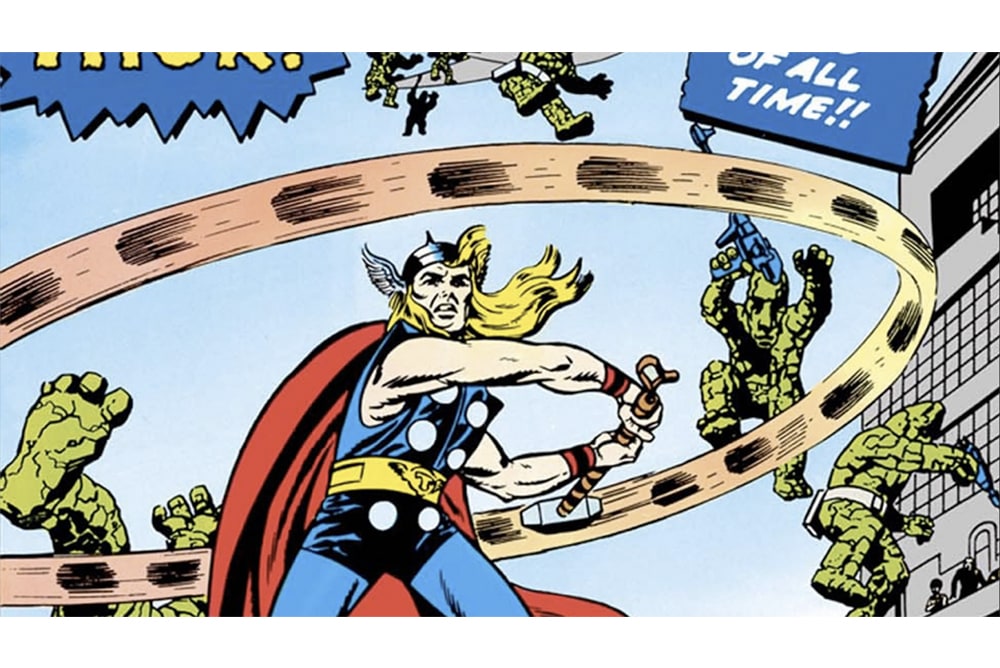

A conservative estimate puts the tally of comic books, strips, ads and related ephemera that Sinnott has worked on as penciller, inker or cover artist at well over 4,000. The overwhelming majority of that work is with Marvel Comics, arguably the industry’s dominant creative force and unquestionably the one most responsible for our current superhero-saturated popular culture. He began freelancing for the company’s then editor-in-chief, Stan Lee, while he was still a student and the company—then known as Timely—was better known for its Westerns and war stories. Between 1950 and the early ’90s, Sinnott worked on nearly every title in the company’s roster, from Avengers to X-Men. He was the inker for the first appearance of Thor—now one of Marvel’s most popular characters, on the page and screen—and for dozens of subsequent stories starring the hero. And beginning with issue number 5, in 1962, he inked nearly 300 issues of Fantastic Four—the title widely credited with establishing Marvel’s brand—including a five-year run with series co-creator and comics legend Jack Kirby.

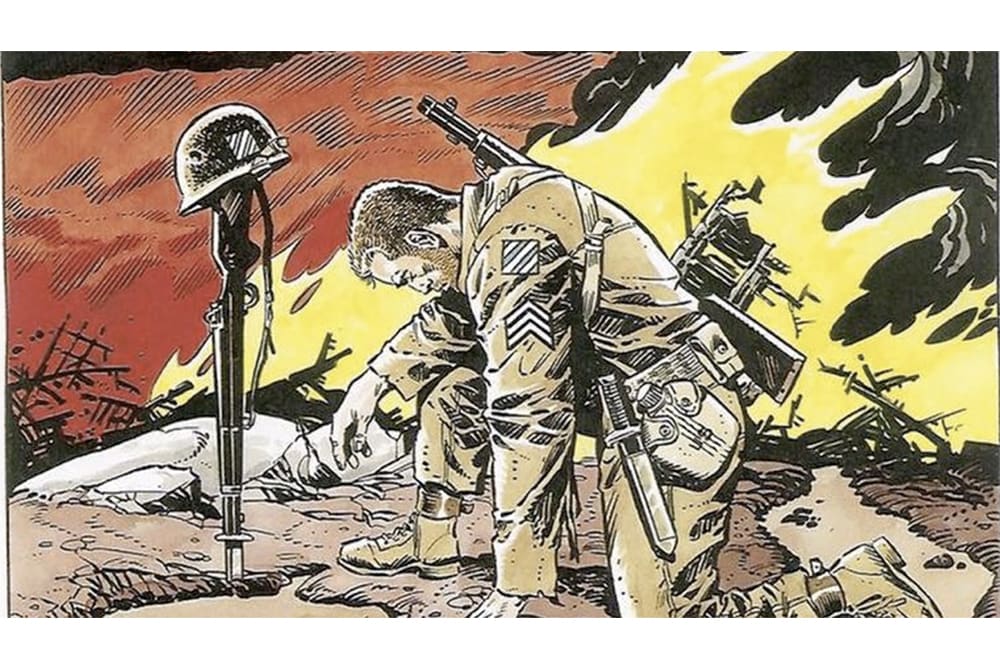

Just as he was present for the origins of many superheroes that, more than 50 years on, show no sign of lessening their hold on the popular imagination, Sinnott was also witness to the foundational years of the School of Visual Arts, back when it was a modest operation known as the Cartoonists and Illustrators School. Like many early students, he attended under the GI Bill, having served in the Pacific theater with the Navy during World War II. After graduating, he moved back to his hometown of Saugerties to raise his family and establish a long-distance relationship with Marvel.

Though Sinnott has lately stepped away from the demands of full-length books, he still works with Lee. For the last 27 years, he has inked Lee’s Amazing Spider-Man Sunday comic strip, syndicated in newspapers nationwide by King Features. And his past work continues to draw an audience: Sinnott regularly attends comics conventions in the Northeast, and this July, Hermes Press will publish Joe Sinnott: Embellishing Life, a 240-page hardcover collection of selected work.

You’ve been working on the Amazing Spider-Man Sunday strip for nearly 30 years. What’s the process of putting it together?

Every 10 days I get two strips, always six panels to a strip. Stan writes the story, and he sends it to Alex Saviuk, who pencils it. Then Alex sends it to a great letterer, Janice Chiang. She lives in Woodstock, only eight miles away, and sometimes, if the deadline is tight, she’ll bring it down to me in person. After I ink it, I bring it to the FedEx drop box and send it to Stan, and he’s got a coloring department out there [in California] that colors it, and from there it’s sent to the printer. We work pretty far in advance. In November, we’re doing February’s strips. It’s a long process, actually.

How long have you worked with Stan Lee?

Would you believe 68 years? I met Stan by working for [early SVA faculty member] Tom Gill, as Tom’s assistant. Tom had an account at Timely, and I worked on Kent Blake and Red Warrior for him.

I worked for Tom for about nine months, then I got married and said, “Stan’s buying my work through Tom Gill, I’m going to see if he’ll buy it on my own.” So I went over and Stan gave me a three-page story, “The Man Who Wouldn’t Die.” I spent a whole week on it before I brought it back—I wanted to make sure I did it right. After that, Stan gave me all the work I could handle and he paid very well, $35 a page, which wasn’t bad at that time. I could do a page a day, so by the end of the week I was making a couple hundred dollars.

It was a great time to be in comics, it really was. The stories were so much fun, five or six pages, not like the superhero stories are now, and we did Westerns, science fiction, love stories, everything. And Stan was a great editor. He was only about 26 years old then. If he wanted to show you how to make a picture better, he’d jump on the top of his desk and go into a motion. He should’ve been an actor.

When did the business turn toward the superhero stories that we know today?

Not long after the Comics Code [a self-regulatory authority formed in 1954], we went belly up for about six months. Nobody could get any work. It was a great turning point. I remember when Stan called us back up, we worked for about three years doing monster books, horror stories like [rival publisher] EC’s. They were a lot of fun to do and sold fairly well, but it wasn’t the big trend that Stan was looking for.

And then in 1961, at the prodding of Martin Goodman, the publisher, who saw that other publishers’ superhero titles were selling well, Stan and Jack Kirby created Fantastic Four. And in three months’ time he got the report back that they sold like crazy, and that was the beginning of our superheroes.

Superhero stories are so culturally dominant right now, it’s hard to imagine an era of comics when they weren’t at the fore. But why do you think comics in general are so popular?

I think it started in the 1930s. Not only did we have [comic strip] Dick Tracy but in 1934—that was the big year—we got Terry and the Pirates. I was about eight years old, and every day to see Terry, another kid, go through all these adventures? You can’t imagine how exciting that was. Then came Flash Gordon, Barney Baxter, Tim Tyler’s Luck—all in the early, mid-1930s. Then of course what came because of those were the comic books: 1938, Action Comics [which introduced Superman]. It was just exciting stuff that had never been seen before.

I go to some of the [Comic Con] conventions—I go to Albany every year, and for the last few years I’ve been going to Providence, Rhode Island. San Diego, I went there once, in 1995. That was a madhouse. I had a kid come up to me, his name was Rufus and he was from Ireland. He says, “I want to show you something.” Takes off his shirt and pants. All on his chest, his back, his legs, was a complete copy of one of the comic books I did. It was perfect! It was like they took my book and laid it on there and printed it. I said, “Rufus! What in the world did your mother say when you walked in the door and showed her your chest?” Some of those guys are crazy [laughs].

What was Manhattan like when you were a student? I imagine cheaper?

I lived on 74th Street, between Amsterdam and Columbus Avenues, in a beautiful building—everything marble and brass, elevator operators in uniform, and it was owned by [actress] Fanny Brice. Holy Moses, it was like a mansion!

Rent was only a dollar a day and I got by on another dollar a day. Every morning I would have breakfast right around the corner—10 cents, coffee and a donut. I’d take the subway, the IRT, 10 cents, go to the school. At school I’d go to the machine, get a peanut butter cracker and a Pepsi Cola, 12 ounces, a nickel each. Suppertime, most every night we’d go down to Times Square, to Romeo’s, you could see the guy in the window mixing the spaghetti and get a plate of it for 35 cents. And if we wanted to go to a movie, it was 10 cents for a double feature. So what have I spent, 75 cents? Then I’d go back up to 74th Street and buy a copy of the night paper, the Journal American, for 2 cents. And sometimes I’d buy an ice cream cone for 10 cents.

What was SVA, or the Cartoonists and Illustrators School, like back then?

They had a couple rooms up on 89th Street. [Cofounder] Silas Rhodes, he was a good guy. He was a strong-looking guy, we used to call him Rocky. And [cofounder] Burne Hogarth, he was a character. He had the biggest ego, next to Stan Lee, that I can think of. There was nothing Hogarth liked better than to come into our classroom, go up to the easel and draw anything you asked him. He’d say, “What do you guys want?” And they’d say, “A saber-tooth tiger.” And he could do it, you know?

Our first year was nothing but foundation. We had two great models, the one guy was a student, Johnny Belcastro (G 1952)—he went on to be a comics illustrator, too, under the name Jack Bell—and the girl was named Cecily Hicks. We’d have three-, two-, five- or 10-minute poses, and the model had tights on, and you had to put them in a costume, a cowboy outfit or whatever.

For instructors I had Maurice Del Bourgo and Tom Gill. Tom was doing the Lone Ranger, and pretty soon I started working for him. Comics were very big in the 1940s, ’50s. If you were halfway decent you could find work.

Was your own childhood love of comics what got you interested in becoming an illustrator?

I just love to draw. Even when I’m not drawing for someone, I’m sketching. If I’m sitting at the dining room table or breakfast table, I draw on envelopes, anything that’s handy. Even right on my drafting table. I’ll clean it every few years. I’ve had it since 1951, I think. A lot of art has come off of here.

When I was growing up, my mother rented out two of the rooms in our house. We had seven kids in our family and with my father and mother that’s nine, and then with the two rooms booked, usually by schoolteachers, that’s 11 people, right? And we had one bathroom [laughs]. Can you imagine the line in the morning?

Anyway when I was three years old, one of the teachers gave me a box of crayons for my birthday, and I loved those crayons! I used them till they were down to nothing. I’d draw on paper bags, I’d draw on sidewalks, I’d draw on anything I could. I was always drawing, drawing, drawing. My father was very talented. I remember his black lunch box—he’d take a pen knife and scratch drawings all over it, beautiful scenes. A couple of my brothers were talented but they didn’t keep it up.

One time there was a roomer, he was a cook at one of the restaurants in town, he had been in the German submarine service in World War I. And where he worked he had to wear a white shirt, white pants and a white hat. He’d come home from work and sit on the chair in the parlor and I’d sit on the arm of his chair. I was only a little kid, five or six years old, and he’d say, “Joe, get me a pencil,” and he’d draw on his pants, cowboys and soldiers. To me, at that time, I thought he was the greatest. He could draw, you know? I always felt like he was the one who inspired me. His name was Bill Thiessen, and after a couple years he moved away and it was like missing part of the family. I wish I could’ve met him years later and showed him what I did. I think if it wasn’t for Bill, and certainly Tom Gill, I wouldn’t be drawing.

After some 70 years in the business, is there anything that’s still hard to draw? Anything you don’t like to do?

Horses aren’t easy. Wheels—I hate motorcycles, I hate spokes, I hate stagecoach wheels. Even with Spider-Man, there are a lot of street scenes where you draw cars.

There are some things you don’t like to draw, they take too long. Fire escapes are a no-no, you don’t like drawing those. I tell Stan, “Get Spider-Man out in Monument Valley [laughs]. No perspective, just rocks!”

A version of this article appears in the spring 2018 issue of the Visual Arts Journal.

For more SVA Features videos, visit SVA's YouTube channel.

SVA Features asset