SVACE Illustration and Comics faculty member Stephen Byram shares best practices and trial-by-error tips for navigating copyright law as an artist in the music industry and advertising world.

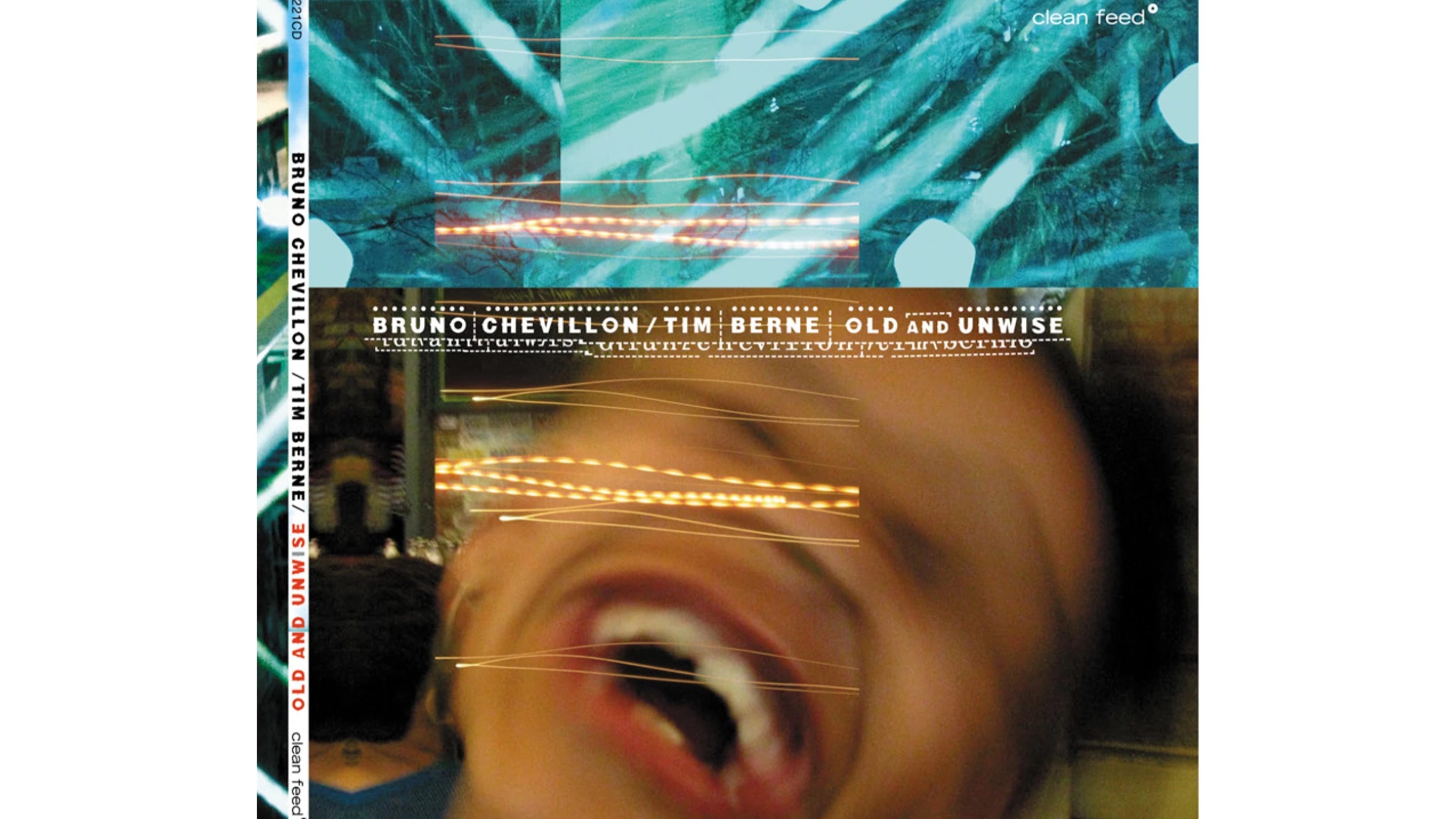

Stephen Byram, no title, 1995, digital collage utilizing the photography of Tim Berne, 5.625" X 5.062", Cover image for Bruno Chevillion/Tim Berne “Old and Unwise” CD package, Clean Feed Records - CF 221CD, 2011

When not designing album covers for major record labels, Stephen Byram teaches Collage Improv (Course Number: ILC-3422-OL), a class where continuing education students are tasked with minimal planning—strictly no rough sketches or layouts beforehand. Each week students come ready to create a full piece in three hours with an assortment of collage materials provided by Stephen. Might sound like a fun challenge, but collaging using other people's illustrations and photos could get you into some deep financial and social trouble, especially if you plan on selling your work or you're being commissioned for what you're making. The SVACE Illustration and Comics faculty member sat down with us to discuss his best practices for avoiding copyright infringement when collaging.

How did you learn to navigate copyright law as an artist?

SB: I’ve spent my career as a designer exclusively in the music industry. Early on I worked for major labels, CBS Records, RCA Records and Sony Music. Each company had large legal departments that kept a sharp eye on images, design and music to make sure there was no exposure to copyright suits. My work as a designer and art director was considered “work for hire” and thus the property of the label. Illustrators, photographers and designers that I engaged for projects were bound by contracts that assigned copyright and usage terms. This informed how I view the world and gave me a deep respect for the work of others and a sensitivity to the hot water one can get into when you rip something off.

I’ve also worked as an illustrator and fine artist, with collage being my chosen medium. I never appropriate photography to use in my work without permission of the photographer. I have sampled imagery from a variety of sources in order to create textures and compositions. I always process this material to the point where it is unrecognizable. I never lift anything straight up without written permission of the image creator. On occasion, I might take something from the public domain, an engraving or vintage photograph, but will always add to or subtract from it to alter its meaning.

Can you speak to a time when copyright infringement posed an issue for you?

SB: It never really has, I’ve always stayed on the ask-before-you-take side of the line. But please allow me to go off on a few tangents.

This is not really a copyright issue per se, but when I was a young AD [art director] I commissioned a piece from an illustrator. What he turned in I felt lacked impact. Without asking him, I hammered a large nail through the center of the piece, which I thought was quite cool and resolved the illustration. The artist was NOT pleased with my move, however, and let me know in no uncertain terms what an ass he thought I was. For other reasons, the piece was not published. He was paid in full and the piece returned. I maintain that the piece was improved, but what I did was wrong and I regret my youthful butt-headedness.

I came up as a designer pre-computer/Internet. Back then, if you didn’t make the art or take the photograph yourself you either had to commission it or buy the rights to use an existing piece. There was no easy place to go to lift something, it was a more straightforward process, or so it looked at the time.

With the digitization of everything there was all this stuff at your service ready to use. Before the computer, when you had an idea for something you sketched it, scribbled it or explained what it would be and the client/boss/whomever would try to imagine it. If you were successful in your storytelling and they bought it, you then executed the piece. There was a good amount of wiggle room from mind’s eye to in front of you and that allowed for things to evolve and improve. In the digital era it’s easier to simulate how your idea will look by adapting and modifying images that already exist or by appropriating imagery you didn’t create or own. Unfortunately, clients would rather not have to try to imagine something or take your word for it. This coupled with the belief that anything you find online is free causes problems.

On the other hand, there is fine art where appropriation is an established strategy ... ́as long as you create something new with it or expand its meaning.

When was the last major time that you or an artist you’ve worked with had trouble navigating copyright law? Can you share a bit about that experience?

SB: I was doing a record package for a guitar player a few years back. It was a retrospective compilation of his work. He had a number of photos he had acquired over the years, taken by various photographers. I really had to lean on him to get usage permissions for their inclusion in the package. That takes time to do and he wasn’t keen on spending that time. At the end of the day, spending time is cheaper than a copyright suit. I also told him that I refused to include any image in the design he didn’t get cleared for usage.

If you are inspired by an artist and want to create similar work, how do you differentiate theft from inspiration? Where do we draw the line?

SB: Well if you copy something straight up, not as an exercise, that might be theft (or forgery). Inspiration does not mean copying. I would never intentionally make a work that’s similar to the work of another.

After spending years looking at and studying art, certain influences will present themselves and be absorbed. We are all blenders of a sort, I believe, and after you work your craft for a long while it all collides and combines with whatever you bring to the mix and becomes your own.

If whatever I’m doing does remind me of something I’ve seen, I try to seek it out to make sure that I’m not plagiarizing anything—if I am I burn it down and start over.

How do you recommend gathering copyright-free material to use for collage projects or other artistic endeavors?

SB: Make sure that it truly is copyright free or in the public domain. Transform whatever you take into something different that reflects your unique vision. Collage is all about deconstruction, rebuilding and alchemy.

Stephen Byram, capitolismos, 2008, digital collage utilizing vintage postcards, 12" X 10.75", Proposal for cover image (unused used) for the Brian Wilson record “That Lucky Old Sun” Capitol Records 2008

If you are interested in collage work and further instruction from Stephen Byram, check out Collage Improv by searching for the course number ILC-3422-OL at sva.edu/ce.