A feature from the spring/summer 2022 ‘Visual Arts Journal’

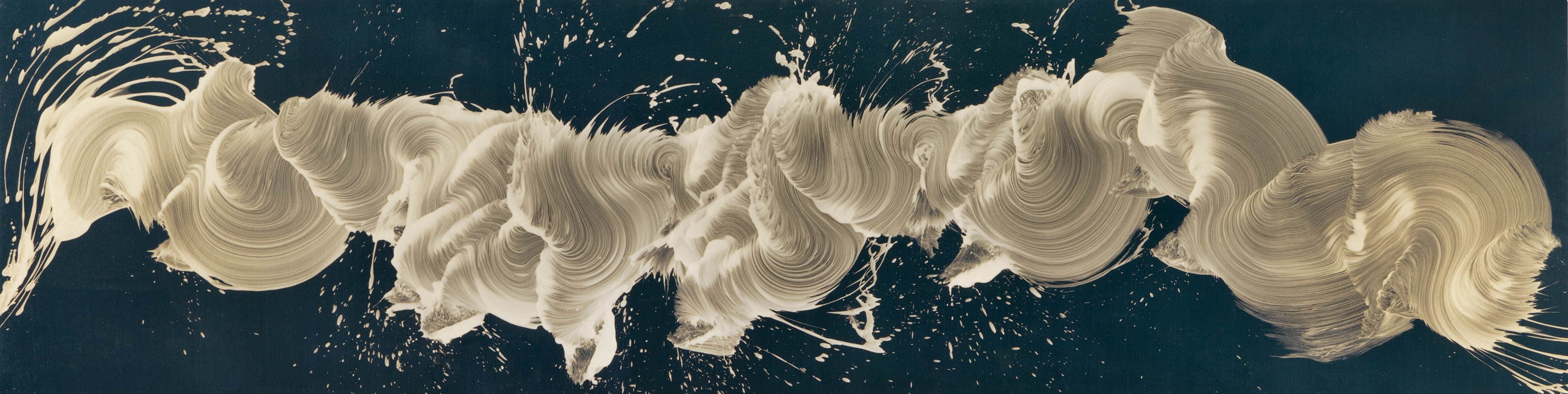

Jamie Nares, What’s Not Obvious, 2010, iridescent pigment and wax on linen, 37 x 144 in.

In 2011, the artist Jamie Nares (1975 Fine Arts), mounted an industrial high-speed camera into the back of an SUV and for the next several days rode through Manhattan, filming pedestrians doing pedestrian things—crossing avenues, sheltering themselves from the rain, hailing cabs—at 860 frames per second. The resulting footage, which was edited down, played back at 30 frames per second—about a 30-fold slowdown—and soundtracked with guitar by musician Thurston Moore, became Street, an hour-long video and arguably Nares’ best-known work to date.

Throughout her career, Nares has experimented with the ways that motion can be documented; her 2019 retrospective at the Milwaukee Art Museum was called “Nares: Moves.” Nares’ methods can be low-tech and unfussy or near-scientific in their precision and sophistication. She has presented abraded sheets of sandpaper as art, and she has created multiple-exposure photographs of pendulums swinging and dancers performing. She makes large-scale gestural paintings with homemade brushes whose filaments and feathers have been chosen for their unique mark-making qualities, and with a brutish machine that was built for laying road lines on asphalt. She has filmed a concrete ball rolling down a West Side Highway off-ramp, struggling to keep up as she runs behind it with the camera, and she has made super-slo-mo, high-definition video portraits of peers and loved ones, in which even the slightest changes of expression unfold in precise detail.

In Street, the slow-motion speed of the footage transforms seconds-long shots of New York City’s diverse street-level bustle into dreamy, dense tapestries of what Nares calls “mini-narratives,” which are subject to all kinds of interpretation. The rare people who notice the camera serve as “the Greek chorus,” she says, periodically breaking the movie’s odd spell to regard the audience as the camera passes by. The late writer Glenn O’Brien, a longtime Nares friend and admirer, described Street as “an ‘angel’s eye view’ of humanity.”

Despite this quality of reverie, the film can also be seen as a straight anthropological study of a specific time and place. “Street revealed a certain thing about how people self-choreographed in crowded streets,” says critic and SVA faculty member Amy Taubin, another longtime friend and admirer. Seen now, a scant decade later, with our brains and behavior scrambled by two years of pandemic life, “it’s become a historic artifact,” she says. “The choreography of the street is totally different now.”

Jamie Nares, Street (excerpt), 2011, HD video, 61 min.

Born and raised in England, Nares moved to New York in the early 1970s to attend the School of Visual Arts, having read that several artists she admired, like Vito Acconci, Mel Bochner and Joseph Kosuth (1967 Fine Arts), taught at the College. As it turned out, she would never study with any of them. Not realizing she needed to register for courses in advance, Nares showed up for the first day with nothing on her schedule and had to sign up for what few options were left.

This didn’t matter much, in the end. Known then as James, she arrived at SVA “pretty much knowing what I wanted to do,” she says, and already making accomplished work. One day, she and a friend surprised their sculpture class by staging Nares’ Shelf (1974), for which they laid on diagonal platforms that Nares had mounted on opposite walls of the studio and silently stared at each other. (The instructor, artist Richard Van Buren—“a real beatnik type,” Nares says—was apparently delighted.) Within a year, she would be an integral part of the thriving arts community that lived and worked in the Tribeca neighborhood of lower Manhattan.

“There was an incredible cross-pollination of disciplines happening,” Nares says, and in between odd jobs like sandblasting, plumbing (an early call was to fix composer Philip Glass’ toilet) and silk-screening fabrics, she not only pursued her own multifaceted practice but collaborated freely with others in what came to be known as the No Wave movement, so called for its “feigned indifference to just about everything,” she says. She operated the camera for no-budget films by director Eric Mitchell and artist and musician John Lurie; played an onscreen role in G Man (1978), co-directed by former classmate Beth B (faculty, BFA Fine Arts; BFA 1976 Fine Arts); and directed her own feature, the farcical Rome ’78, a No Wave touchstone and favorite of then-Village Voice critic J. Hoberman. She was an early member of the Colab artist collective and co-founded New Cinema, a theater that showed Super-8 and 16mm films that had been transferred to video for screening. And she played in two foundational No Wave bands: as the original guitarist for James Chance and the Contortions, and the drummer for the Del-Byzanteens, which also featured filmmaker Jim Jarmusch on keyboards and sound artist Phil Kline on guitar. Though the latter act was “not much more than a lark,” Nares says, they had a hard-working manager and played often enough that Nares supported herself “for a year or so” on income from their shows.

“There was a lawlessness back then,” says B, who recalls driving a car into the East River, with no fear of repercussions, for one of her films. Even in a scene crowded with underground legends-to-be, Nares, she says, stood out for her “extraordinary, ethereal” charisma and her ability to fluently channel the “insanity” of the time through conceptual films like Pendulum (1976), in which a large sphere hung from a catwalk swings with seemingly dangerous abandon on an empty city street.

“It so vividly reflected this kind of disturbance, this feeling of being unmoored from one’s beginnings in life and one’s family,” B says. “And it was also emblematic of New York City as a playground and canvas. I think Jamie was able to have real freedom. There were no rules.”

Jamie Nares, Pendulum (excerpt), 1976, Digibeta tape, 17 min.

In 1975 Nares began creating—and filming herself creating—what she calls Giotto Circles, works for which she rotates either her arm or a self-made etching tool to inscribe what looks like a precise circle on a wall. (In reality, Nares says, the shape is slightly oval, owing to the mechanics of the shoulder.) The pieces are named for the pre-Renaissance artist, who was reputed to have drawn a perfect circle freehand, and what is remarkable about Giotto Circles is less the symmetry of the produced shape, and more that something so seemingly exact could be made with the simple action of windmilling one’s arm.

As objects of formal beauty that double as records of performances, these circles would be forebears of what has become Nares’ signature artistic project: an ongoing series of works, begun in the 1990s, known as “brushstroke” paintings. Consisting of a single gesture made with one continuous movement on a grand scale, these reduce the act of painting down to its most basic building block, and ask viewers to consider the limitless possibilities for expression contained in that element alone. A Nares brushstroke can be spattering and wild like a wave; it can swirl and zigzag like a wet mop on a floor; or it can flutter like fabric in the air (a phenomenon Nares has explored in the videos Cloth (1998) and Thread (2010).

While they look like unmediated and spontaneous compositions, brushstroke paintings are more often the painstaking result of a repeatedly rehearsed movement that Nares executes as she travels the length of the canvas—which can measure up to 25 feet long—sweeping and twisting the brush as she goes. She begins each one with an intention or gesture in mind, and will make however many passes at the canvas are necessary to get it right—a process that can sometimes take a full day or more.

“The extraordinary thing about the brushstroke works is how Jamie incorporates the elements of performance art—the stamina and the acrobatics—into the paintings,” Taubin says. “It really is a physical dance extended onto the canvas.”

To make all of this possible takes considerable engineering. So that she can make quick and successive attempts at a painting without breaking focus, Nares and her assistants essentially varnish the canvas, giving it a smooth surface that can be squeegeed clean again and again. The paint is mixed with mineral spirits and liquid wax, giving it a motor oil-like consistency. To keep the paint from dripping and running, the canvas lies flat while Nares works from above. For a while, she painted on canvases laid on the floor while suspended in a harness on a pulley. These days, the canvases are placed on a large table that has a trough beneath a drain hole at the far end. This collects the paint from unsatisfactory takes, so that it can be reused.

The brushes Nares uses are their own works of art. She has built, by her estimate, hundreds of them, each with a specific scale and mark-making quality in mind. She is well acquainted with the properties of different bristles and feathers, and the pros and cons of different handle types. A section of her Long Island City studio is dedicated to brush building, with drawers full of parts, and dozens of finished models—“all characters in my drama,” she says—hang near her painting table in irregular rows.

The success of Street has encouraged Nares in recent years to “revisit my old art-making process of doing whatever came to mind,” she says. “I’d always been doing different things but not showing them, because I was concentrating on painting.”

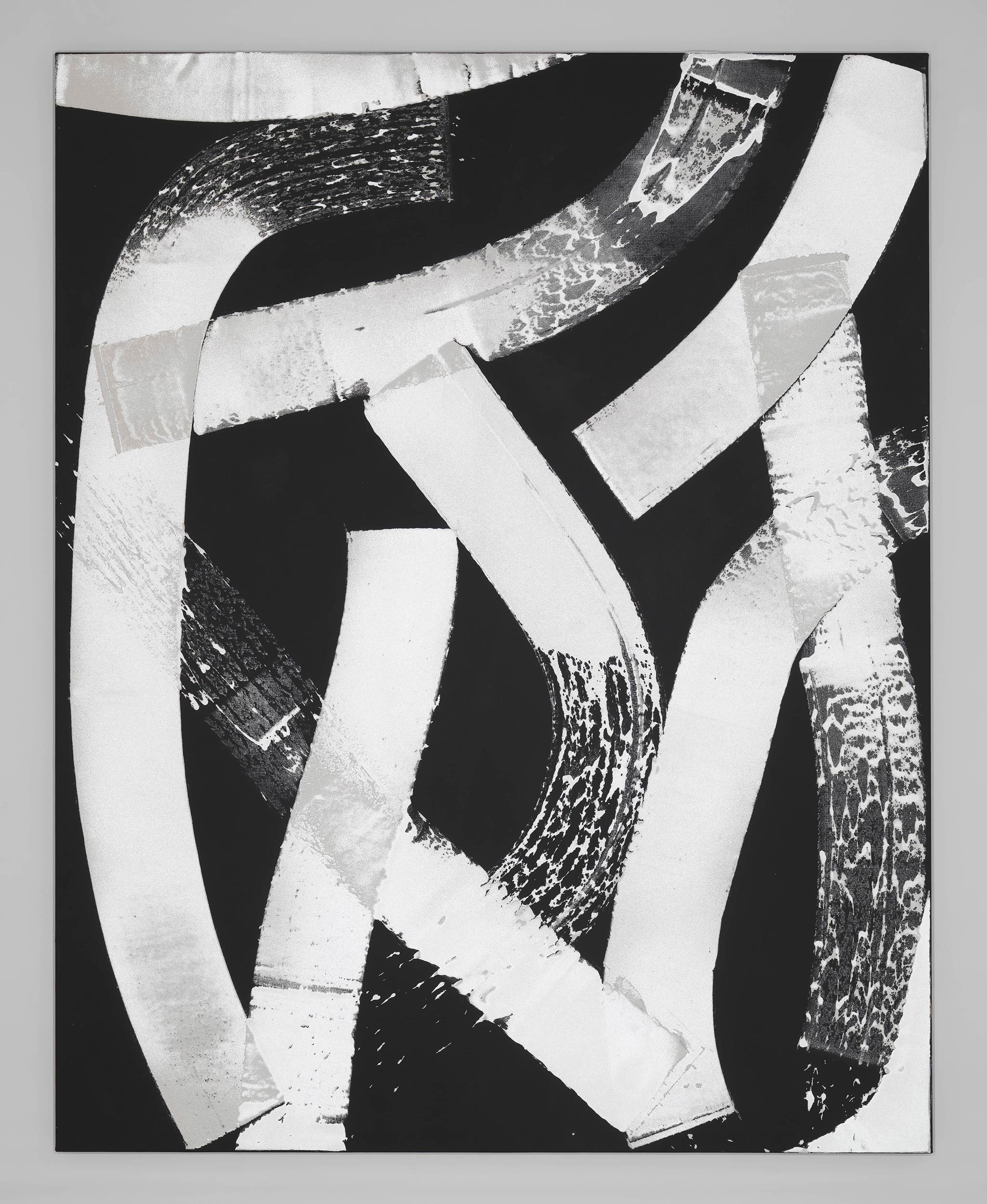

In 2013, Nares debuted her “Road Paint Paintings,” a series of black-and-white works created with a road-line painter that she found and bought online, having long been fascinated with the machines. The paint, actually a melted thermoplastic, is thick on the canvas, and dusted before it dries with tiny glass beads made to reflect headlights in the dark. From certain angles, the works glitter. “There’s a toughness to the road paintings,” Taubin says, an uncompromising solidity that provides ballast to the often weightless brushstroke works and the similarly floating Street.

Continuing in this vein, in 2019 Nares began making “Monuments,” a series of wax rubbings of 19th-century sidewalk stones in downtown Manhattan that are gilded with 22-karat gold leaf. Cut from granite, with grooves hand-chiseled into them to keep pedestrians from slipping and worn soft over time, the blocks offer a variety of alluring textures and patterns.

“Monuments” is obliquely political—a tribute to the “anonymous immigrant laborers who built the city,” Nares says, and made by an immigrant herself at a time of heightened anti-immigration actions and rhetoric. The gilded pieces (commemorating Gilded Age construction, Nares points out) recast those laborers humble work as an inscrutable, awesome achievement from a long-ago civilization. They’re another record of movement in the artist’s catalog, enshrining a form of communication, however obscure, from an increasingly distant past. In making their marks, the workers “inevitably fell into patternmaking,” Nares says, “because that’s what people do.

“There’s something very intimate about that. It’s like a little trace or something.”

A version of this article appears in the spring/summer 2022 Visual Arts Journal.

![James Nares, Laight I, 2018, 22-karat gold on Evolon, [129 x 77 x 2 1/2 inches]. Courtesy of the artist and Kasmin Gallery.](https://media.sva.edu/image/upload/c_scale,f_auto,dpr_auto,q_auto/multimediaBlock/s22-portfolio-nares-monuments-laight-i-2018-1657829878.jpg)