Sophia Dawson

In conjunction with the ongoing exhibition “Correspondence: The Installation,” I recently conducted an interview with artist and activist Sophia Dawson about the show. In the interview, Dawson discusses the origins and inspiration for the “To be Free” painting series that’s featured in the exhibition, her accompanying book Correspondence (Maria Editions, 2021), and some of the things she hopes viewers will take away from an encounter with her work. (The following transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity.)

Jeff Edwards: You’ve been working on the “To Be Free” series for over a decade, and you’re drawing from a history of Black activism in the U.S. that goes back more than four decades, but it feels like this show couldn’t be more timely. What are your thoughts on how this work relates to what’s going on in the U.S. right now?

Sophia Dawson: I guess when I first started making this work, there was not really room for dialogue for it. It felt like some of it was me just making things up. Or not just making things up; essentially there was no audience that was ready to hear the narratives of the political prisoners, of the people I talked about in my work. I felt like it wasn't being received well.

Once Donald Trump became president, that was the first time that I saw a huge population of people who normally didn't care about the issues that I care about as an artist really start to take a stance and notice things that were going on in the world around them that weren’t right. Fast forward the last year: there were so many doors that seemed open, A lot of people were seeking to talk about.things that were done years ago—like a decade ago, seven years ago—and though the work was relevant when I created it, because of the season and the time that we're in as a country, it's become a lot more relevant, a lot more well-received, and a lot more spoken of, and that's been a very exciting process to watch. I do hope that my work serves as a voice to movement.

I should backtrack and say that I don't take credit for my gift. It's a God-given gift. It's all inspired by the Holy Spirit, and I do think that there is such a thing as divine intervention, and I believe that there’s a lot that the Lord wants to step in and do; since biblical days, he was always looking for a vessel that he could use. And so my work is twofold. It's a form of activism and it’s a form of ministry. It's meant to inspire and uplift people who do care about the narratives talked about in my work, but it's also meant to kind of pose a threat to all the opposing forces, everyone who does not understand the work that needs to be done, or who doesn't agree.

JE: So when you were starting to make the work, did you feel like there wasn't a lot of other stuff out there like that?

SD: Yeah. I mean, if I feel like I've done any groundwork, it’s less about the paintings, and more about the process in which I work with individuals that are featured in my work, actually writing letters, actually going to visit people in prison, actually meeting with family members who have lost someone to police brutality, who have someone who was incarcerated for political reasons, and then moving from there to create the work—as opposed to just following what's trending: the most popular hashtags, what's in the news—building a practice that's rooted in serving God's people. I do feel like there is a bit of a foundation being laid in that area.

JE: In the series, you’re taking historical moments that are often treated as part of the grand sweep of history and narrowing the focus to the lives and experiences of the activists at the center of these moments. I’d love to know more about that: how you decided on that approach, and what it how that relates to your own interests as an artist and a storyteller.

SD: Like I mentioned before, my work is led by the Holy Spirit and so I’ve kind of just moved as I'm directed. Ten years ago I was in an African American history class [at SVA] and I got pulled in. I basically learned about a part of my history for the first time, specifically the narratives of political prisoners, and so there was a freaking in my heart which I know now was the Holy Spirit, that said, "OK, now do something," and I went from making paintings to meeting family members of political prisoners, to them suggesting that I start writing letters, and then the letters turned into everything else.

My goal is just for me to be extremely sensitive to the Holy Spirit. And whatever He directs me to do, I do it. But I know now that a lot of what I'm called to do is aligned with serving people. So whether I'm writing a letter, serving our church, or serving my community, as long as there's a soul attached, that's usually how I know what process to take.

Portrait of Jalil Muntaqim, by Sophia Dawson.

JE: Your book Correspondence deals with your own story as creator of the works in “To Be Free,” and this exhibition deals with both the series and the book. How do you see these works relating to one another in this exhibition and in the future?

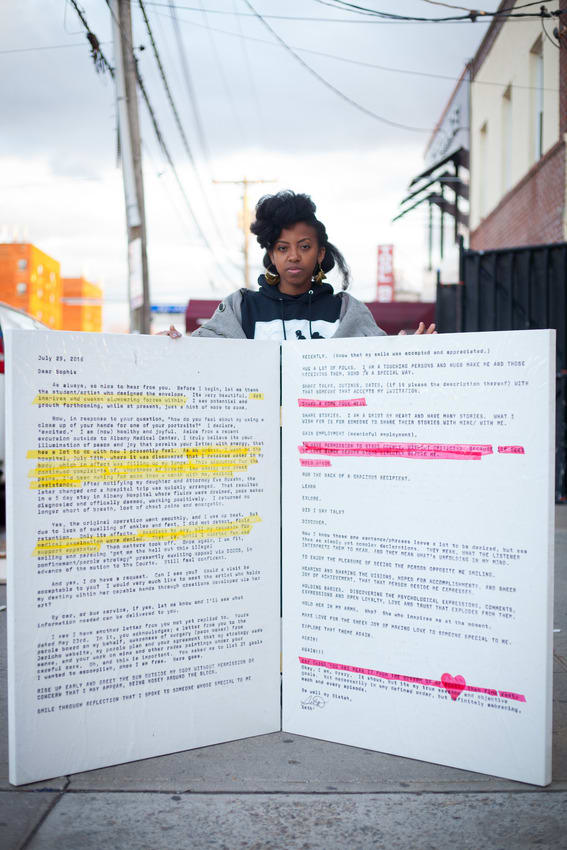

SD: Correspondence is essentially the hidden part of my practice that I never showed. I would incorporate some of the letters and correspondence into the paintings, but I didn't really expose that to the public that much until recently. I think there's even a painting in this show that's just a letter that was turned into a piece of artwork. But when it came down to it, the stories behind every painting, the reason why the paintings even came to be, a lot of that’s in the letters, and so Correspondence shows eight out of the eleven years of correspondence with political prisoners.

It’s also served as a fundraising tool, because as the work was being done, people actually started coming home. So there are about eleven people from the project that are now home and free by the grace of God. They’re elders with felonies on their record, which prevents them from getting basic basic things that they need to live comfortably. I'm talking about people like 80 years old, 70 years old. And so the book is a fundraising tool to help support them post-release as well.

JE: That speaks to something else I’m interested in with your work. You’re both an artist and an activist, and those two roles have often overlapped—for example, you’ve also used proceeds from the sale of paintings from “To Be Free” to help fund advocacy efforts on behalf of the subjects you’ve painted. How do you view the interrelationship of these two aspects of your life, and what are your thoughts on the role of your art as a catalyst for activism?

SD: Well, I can honestly say that I try not to separate anything. So ministry, activism, my art, my life, it really does mesh well and it becomes just a part of who I am. And so my practice is essentially my lifestyle. I don't really separate the two at all. It's intertwined. My son has come with me on prison visits. My son has letters that get sent to him from political prisoners. My students who come out of Rikers Island come to my church. It's all connected. I try not to separate anything.

JE: Before we finish up, is there anything else you wanted to say in relation to the show or your work? Anything you want to leave people with when they're done reading this?

SD: Yes; I would start with the fact that God is definitely a God of justice, and when I started the work eleven years ago, I did not know that people would actually come home. I didn't know that anything would come from it, but He has been so faithful, to have eleven elders who on paper were supposed to die in prison come home by his grace and his mercy. I would also add that folks who care about the cause can definitely support it by buying the book. If we don't do what we need to do now, we'll be talking about history and not living history, and so I guess that that's all that I would say.

And also lastly, that you know this stemmed from a freaking of the heart eleven years ago, and I believe that everybody has that moment with a certain issue. We all have something that's going on in the world that bothers us enough to keep us up at night, but not everyone takes the time to pay attention to it or figure out how they can do something, so I would encourage the audience to figure out what that is for them and how they can contribute to that thing, because this is what it was for me. And there's no contribution that's too small. It doesn’t have to be financial; I started with paintings and now I'm able to have a monetary thing attached to those paintings, so people shouldn't be discouraged. They should look at what they have in their hand and start from there.

Sophia Dawson

“Correspondence: The Installation” is on display through September 10, 2021 in the Flatiron Project Space. To learn more about the exhibition and schedule an appointment to view it in person, visit this page on our events calendar.