The bestselling memoirist and illustrator publishes her latest book, on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this summer.

Writer, illustrator and SVA alumnus Nora Krug (MFA 2004 Illustration as Visual Essay).

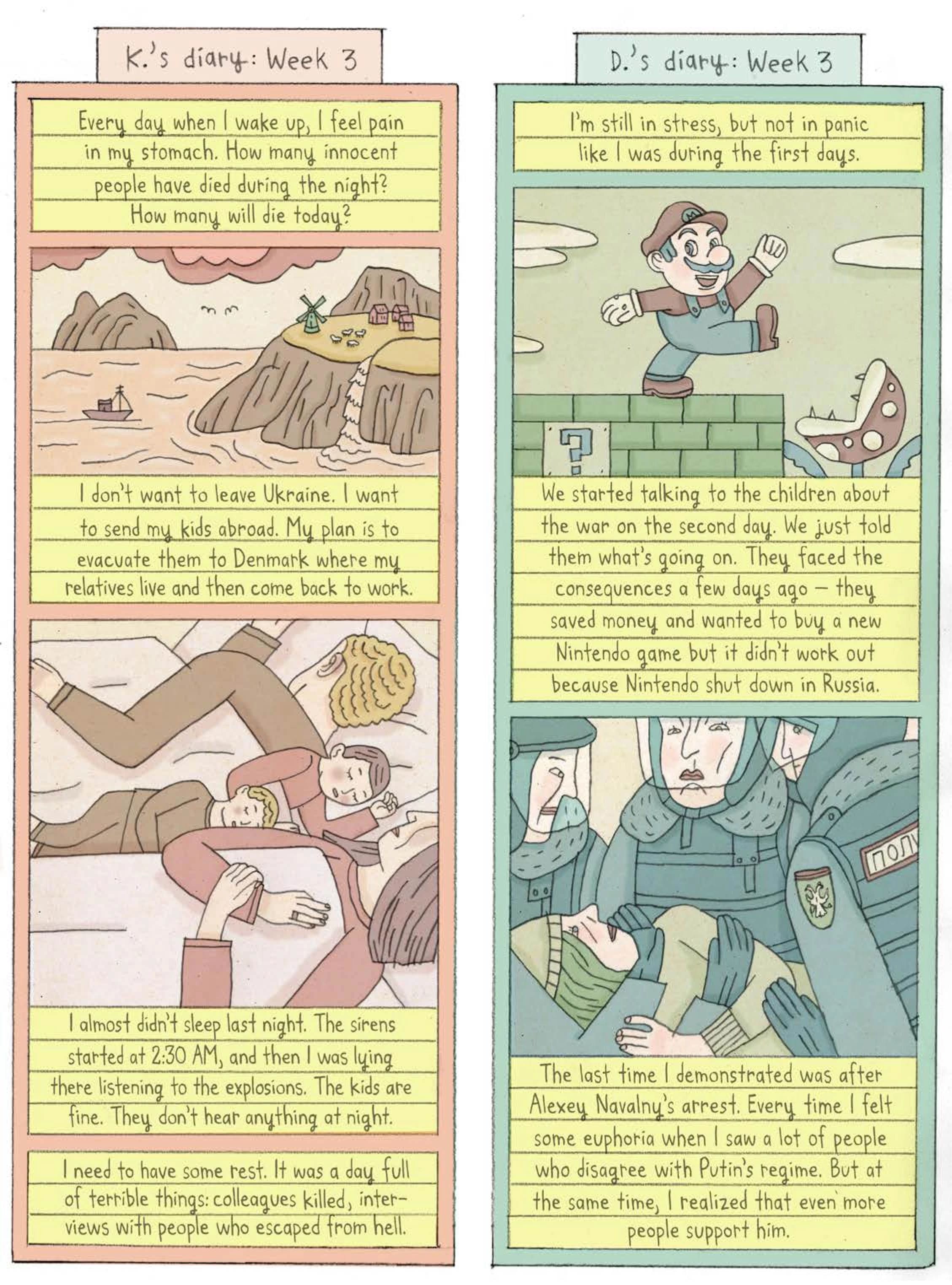

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in February of last year, an unusual series of nonfiction comics by Nora Krug (MFA 2004 Illustration as Visual Essay), a German-born, Brooklyn-based writer and illustrator, began appearing in American and European newspapers.

Each installment consisted of two short columns that presented brief, diary-like accounts of everyday life during wartime. The left column, colored with a warm palette, told the story of a Ukrainian journalist, who is identified only as K. The right column, rendered mostly in blues and greens, told the story of a Russian artist, identified as D.

The two correspondents, both distant acquaintances of Krug’s, each relay grim stories, though the point of the work, she says, is not to draw an equivalence. To the contrary: D.’s experiences pale next to those of K., who separates from her children, mourns the deaths of friends and colleagues, and witnesses the merciless destruction of her homeland. In one early strip, K. plots to evacuate her kids while laying awake at night listening to bombs explode; D., meanwhile, is explaining to his children why Nintendo has stopped doing business in Russia. Still, war also poisons an aggressor nation’s citizens, regardless of their degree of complicity. D., fearing conscription and his government’s crackdown on dissent, eventually separates from his family, too, fleeing the country.

Krug’s series ran, either in its entirety or excerpted, in the Los Angeles Times, in the U.S.; El País, in Spain; L’Espresso, in Italy; Süddeutsche Zeitung, in Germany; and De Volkskrant, in Holland, until its conclusion earlier this year. In August, it will be collected and published as a book, Diaries of War: Two Visual Accounts From Ukraine and Russia, by Ten Speed Press.

“Diaries of War has a clear political standpoint,” she says. “Ukraine is suffering an unprovoked attack, Russia is the perpetrator, and what’s happening in Ukraine and Russia cannot be blamed on a single, despotic leader and his propaganda alone.”

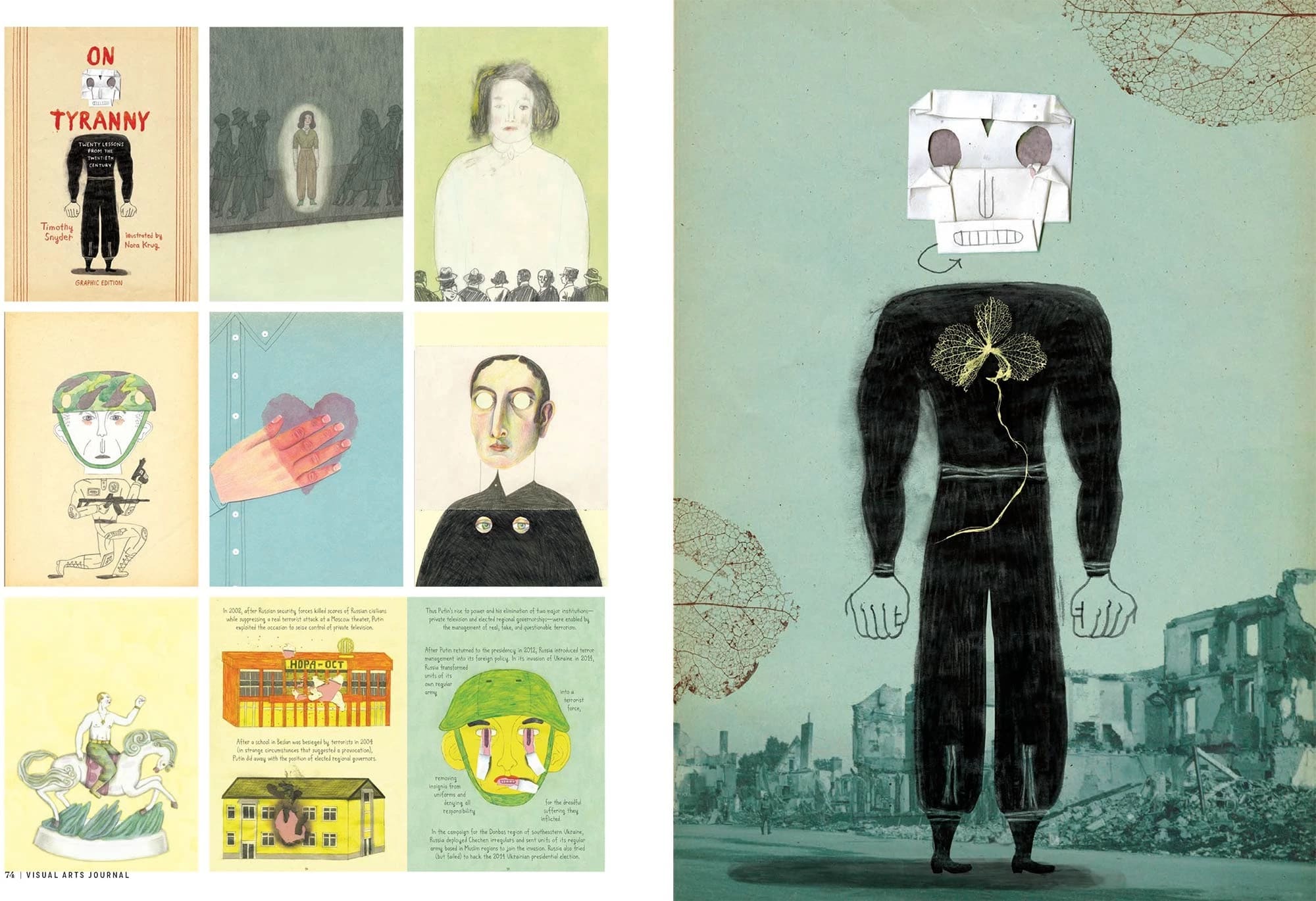

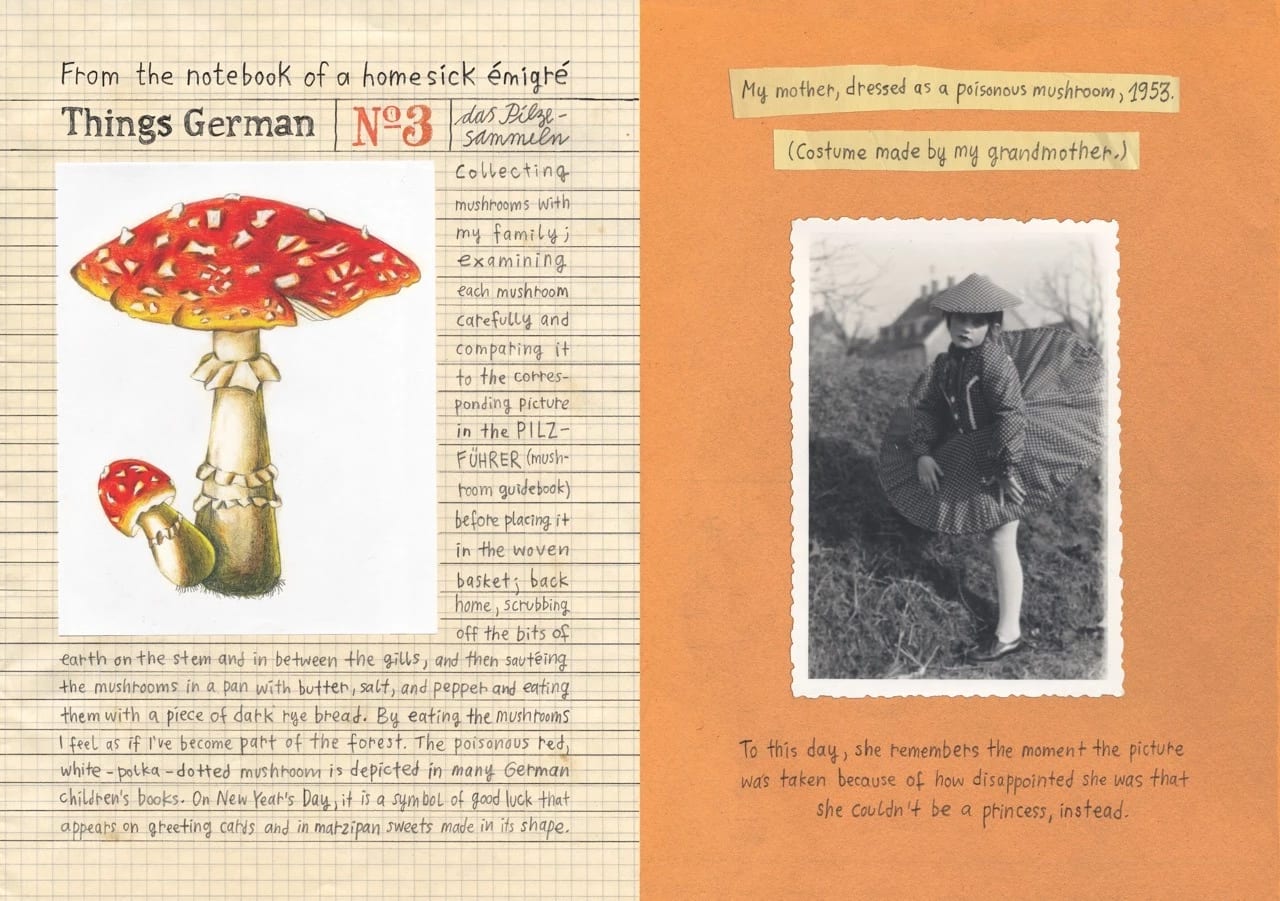

Since the publication of Belonging, her graphic-novel memoir, in 2018, Krug has been widely acclaimed for her dexterous, visually inventive meditations on everything from cherished cultural and folkloric traditions to the horrors of totalitarianism, bigotry and war. In Belonging, Krug investigates her family’s involvement in and experience of Nazi Germany, and her own feelings of shame and responsibility for her country’s dark, not-so-distant past; the book won a National Book Critics Circle Award, a silver medal from the Society of Illustrators and was named a “best book of the year” by The New York Times, among other publications. In 2021, she created the art for an illustrated edition of On Tyranny, historian Timothy Snyder’s book on how democracies can devolve into authoritarian governments, which won a gold medal from the Society of Illustrators, along with other honors. Both Belonging and On Tyranny are international bestsellers, each having been translated into more than a dozen languages.

In March, “Nora Krug: Belonging,” an exhibition of art from the two books, opened at the Norman Rockwell Museum, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where it will be on view through Tuesday, June 13. This comes on the heels of the exhibitions “Illustrator as Witness,” held in 2022 at the Society of Illustrators in Manhattan, and “On Tyranny,” which was on view from late 2021 through last year at the Munich Documentation Centre for the History of National Socialism, in Germany.

At a talk held as part of the Munich exhibition, Snyder spoke about how, after deciding to produce an illustrated edition of On Tyranny, he chose to work with Krug. “When I read Belonging, I thought, ‘It has to be her,’” he said, going on to call their combined effort “a much better book than what it was before. . . . When I now re-read my own book, I see aspects and dimensions that weren’t there before. It was a collaboration, in that sense, and Nora added so many new things.”

Krug grew up in Karlsruhe, a city in southwest Germany near France’s Alsace region, where some towns keep old World War II tanks on display, their cannons pointed toward Germany. “I remember my father explaining this to me when biking through Alsace as a child,” she says. “A political lesson learned early!” As a teenager, she focused her creative energies on classical music and the violin. She always drew and painted, but “didn’t realize at the time that it could be a ‘real profession,’” she says. “I didn’t personally know any illustrators.”

After high school Krug moved to England to attend the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, founded by Paul McCartney in 1996. While there, her interest shifted to the visual arts. She studied set, costume and lighting design in class and designed album covers for friends’ bands on the side.

She also developed an interest in nonfiction narrative. For her final project, she traveled to Sarajevo to film a documentary about the city’s precarious state in the wake of the Bosnian War, “after all the international media had left and when the rest of the world didn’t seem to care anymore,” she says. She visited an abandoned zoo, a psychiatric hospital and the city’s disused stadium, built for the 1984 Winter Olympic games.

After graduating from LIPA, Krug returned to Germany and studied at The Berlin University of Arts. “I had abandoned documentary film, but realized I’m really a nonfiction person, and I didn’t want to let go of that side of myself,” she says. One instructor in particular, artist Henning Wagenbreth, encouraged her to think of illustration as a tool for active engagement with the wider world. Inspired, she applied to the MFA illustration program at SVA and moved once more, this time to New York City, where she continues to live, work and teach—in addition to her professional practice, she has been an associate professor at Parsons School of Design for 16 years. “The field in America is just so much broader,” she says. “I think that there is a stronger awareness here of what illustration can do—of all the ways that it can be applied—and a greater openness toward experimentation.”

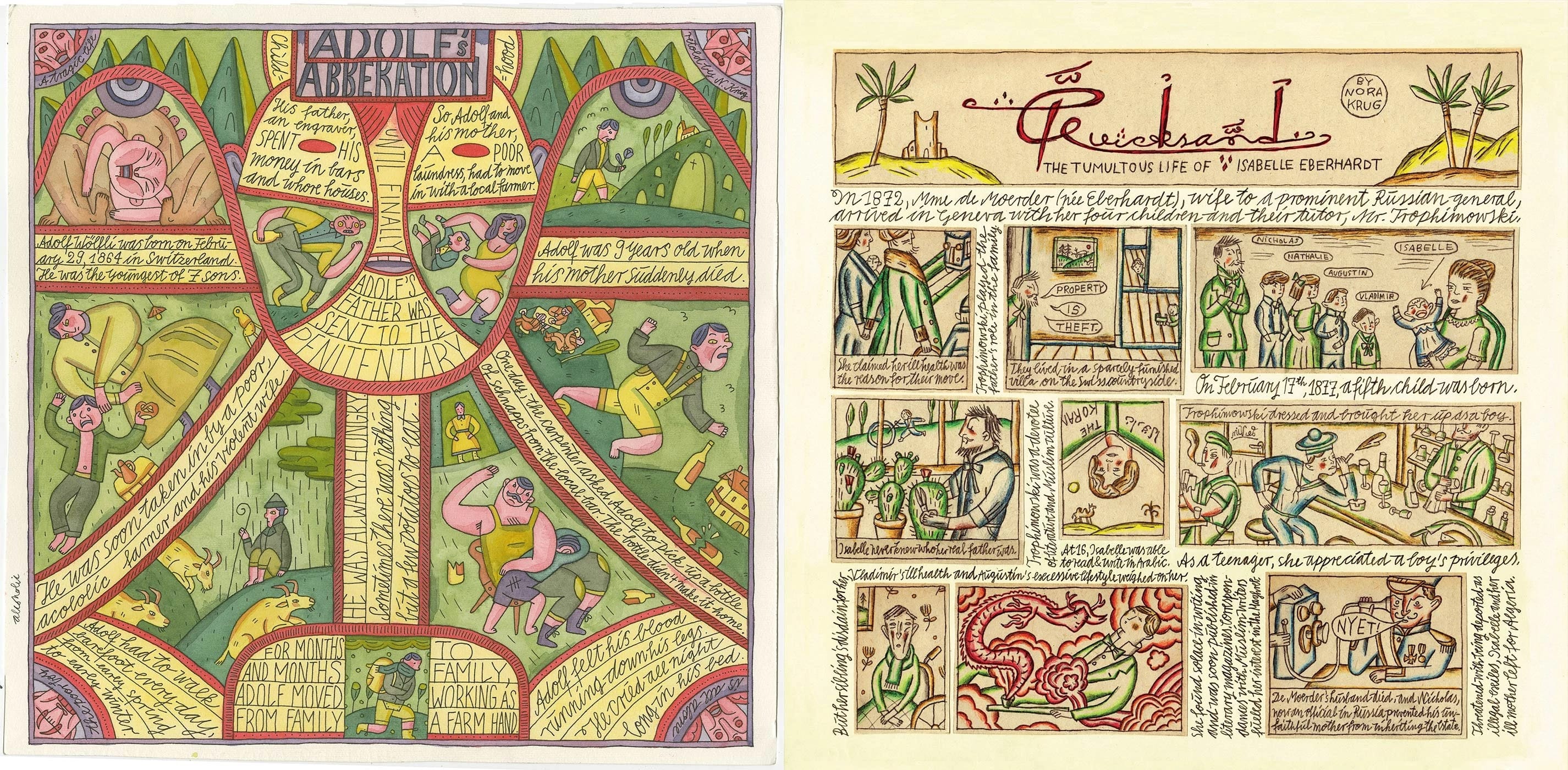

From left: Adolf’s Aberration, a comic by author, illustrator and SVA alumnus Nora Krug about the troubled 19th-century Swiss “outsider” artist and composer Adolf Wölfli; Quicksand: The Tumultuous Life Of Isabelle Eberhardt, Krug's comic about a Swiss-Russian writer and expatriate who passed as a man in late 19th- and early 20th-century Algeria.

For her thesis at SVA, Krug chose to reinterpret the Little Red Riding Hood fairy tale, creating four mini-books that each focused on a different main character from the story. This gave rise, several years later, to her first professionally published book project, Red Riding Hood Redux (2009), a set of five volumes presenting wordless, synchronized narratives from the perspectives of Red Riding Hood, her mother, the hunter, the grandmother and the wolf. (A set of the books is in the collection of the U.S. Library of Congress, as is a copy of Krug’s limited-edition 2014 book, Shadow Atlas, which catalogs legendary ghosts and spirits from various cultures around the world.)

Not long after completing her MFA, Krug met the art director and designer Monte Beauchamp, who invited her to contribute to BLAB! (later known as BLAB WORLD), the comics, art and illustration anthology that he had founded in 1986 and published more or less annually, under various imprints, through 2012. (A new incarnation, Comics and Stories That Will Make You BLAB!, debuted in April from comics publisher Dark Horse.) BLAB!’s roster of artists includes fellow alumnus Drew Friedman (BFA 1981 Media Arts), and former and current SVA cartooning and illustration faculty Bill Griffith, Peter Kuper and Gary Panter.

“BLAB! reminded me of the kind of underground comics anthologies that I was familiar with from Germany and Switzerland,” she says. “Monte’s early support, for which I’m still very grateful, really allowed me to explore my most personal ideas and made me realize that not only the most commercial work is publishable.”

Krug’s three nonfiction comics for the anthology told the stories of former U.S. Army Sergeant Charles Robert Jenkins, who defected to North Korea during the Korean War; Swiss-Russian writer Isabelle Eberhardt, a convert to Islam who traveled through North Africa and dressed as a man; and the troubled Swiss “outsider” artist and composer Adolf Wölfli. The works bear many of the narrative and visual hallmarks for which she is now well known: a line evocative of European folk art, as well suited for humor as it is for tragedy; storytelling informed by historical research; and inventive panel and page construction.

“All of Nora’s work for BLAB! has been exceptional,” Beauchamp says, “but graphically, her take on the life of Wölfli is a tour de force in the genre of comic art, and I think it’s her sensibilities as an illustrator and designer that make it so. Her line work is experimental and captivating, as is her color palette and ability to spin a yarn, and her characters are emotionally charged in a stylistic abstract manner that is uniquely her own. She’s a gem of a creator.”

Krug’s three most recent books have each offered a new challenge. Belonging required unflinching personal honesty. On Tyranny, a work devoted to ideas, not narratives, was an opportunity to work in a more conceptual mode—“attempting to add a poetic layer to Snyder’s political texts,” she says. Freed from the obligation to maintain continuity, she tried to devise a new illustrative approach for each spread.

For Diaries of War, says Kimmy Tejasindhu, Krug’s editor at Ten Speed, Krug has chosen, for the first time in her career, to tell a still-unfolding story. “She’s taken on the responsibility of reporting heartbreaking events in real time,” she says, “serving as a kind of human filter through which these personal stories flow.”

Regardless of the project, Krug likens her process to that of a sculptor’s or editor’s—time consuming, exploratory and self-critical. “I never know what I’m going to draw when I start,” she says. “It’s like a negotiation with the blank page. I’ll add elements and then take them off and try something else. I erase a lot. The work isn’t always enjoyable. I’m very critical throughout.”

Sometimes, the composition incorporates historical artifacts and found objects to simultaneously zoom out while adding a tactile quality. “Found objects reflect both a personal and collective narrative,” she says. “They can communicate stories and emotions in a different way, and give the reader a different insight or access into a particuar period of time.”

Ultimately, every decision is made in service to Krug’s overarching artistic mission.

“I want to convey that we don’t exist in a vacuum,” she says. “It’s our responsibility to face our histories.”

A version of this article appears in the spring/summer 2023 issue of the Visual Arts Journal.