The musician, photographer and SVA alumnus talks about his current book projects: a commemoration of Debbie Harry’s 1981 solo debut, and a forthcoming memoir.

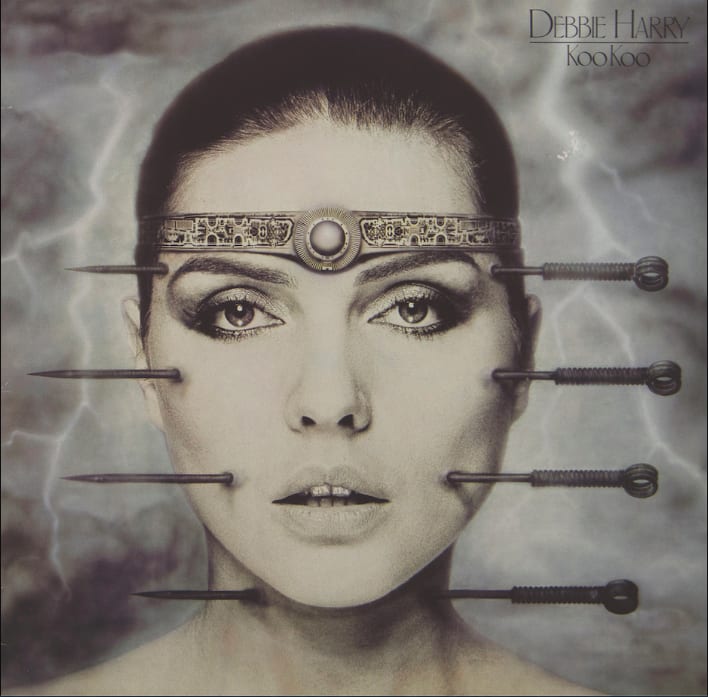

Debbie Harry on the set of the H.R. Giger-produced video for “Now I Know You Know,” from her 1981 album, KooKoo.

The School of Visual Arts has many distinguished alumni, but only one (so far) is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Chris Stein (1973 Fine Arts), who in 1974 founded the band Blondie with singer Debbie Harry, has been a major influence on popular music for nearly 50 years. Blondie has sold more than 40 million albums and continues to tour worldwide, boasting a repertoire of propulsive, catchy and cool hits—like “Heart of Glass,” “Dreaming” and “Rapture”—that endure as playlist staples and inspiration to countless musicians.

Stein is also a dedicated photographer whose work has been collected into three books to date, including Point of View: Me, New York City, and the Punk Scene (2018) and Chris Stein / Negative: Me, Blondie, and the Advent of Punk (2014), both published by Rizzoli. The latest, KooKoo (Kaleidoscope, 2021), presents photos of Harry and Stein’s 1981 collaboration with Swiss artist H.R. Giger—best known for his creature and set designs for Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979)—for Harry’s first solo album, also called KooKoo.

A departure from Blondie’s sound and image, the funk-focused KooKoo featured songwriting and production by Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of Chic and striking visuals by Giger, done in his signature “biomechanical” style. Stein is currently working on a more comprehensive book about the project, with the cooperation of the estate of the late artist, who died in 2014. It is due out from Titan in October.

“Giger is kind of overlooked,” Stein says. “He’s not represented in [MoMA], which I think is a crazy oversight. I think it has to do with his Hollywood connection or that so many people do these Giger-based, biomechanical tattoos—maybe they think he’s too fringe or ‘outsider.’ But the guy has influenced a whole generation of artists.”

Though he is sitting out the current Blondie tour, Stein expects to reunite with his bandmates this summer to start work on a new album; their last, in 2017, was the well-received Pollinator. He recently got on Zoom from his Manhattan home to talk about collaborating with Giger, his art collection (or lack thereof) and SVA stories from his forthcoming memoir, Under a Rock, which will be published next year.

When you set out to make KooKoo, was the idea to do something completely non-Blondie?

Yeah. We were enamored of Chic. And those guys were big rock fans. When we met Nile for the first time he was carrying on about how much he loved Devo, and he claims to this day that we introduced him to rap music, which is odd—“Good Times” was the foundation for a huge amount of early rap stuff.

Nile always says he was disappointed that the record wasn’t more successful. It was the first time we had worked with anybody outside of Blondie, and their first time working with a rock artist. And then Nile immediately went on to have huge successes with David Bowie [Let’s Dance (1983)] and Madonna [Like a Virgin (1984)].

How do you feel about the album now? Do you ever revisit it?

I like it, but I don’t find myself listening to a lot of our old stuff. I hear “The Tide Is High” in CVS all the time.

Is it true that “The Tide Is High” was a favorite of John Lennon’s?

Well, Ringo did a book of postcards that he got from the other Beatles, and one of them is from John Lennon saying something like, “Ringo, you need to do a song like ‘Heart of Glass.’” And Sean Lennon has said that “The Tide Is High” is the first song he remembers from his childhood.

We had brought a copy of [Blondie’s 1980 album] Autoamerican to the Dakota as soon as we’d got copies. I’d never met John but the doorman knew who we were and gave it to him, and apparently he wound up playing it all the time.

The KooKoo books document the work that Harry and you did with H.R. Giger for the project. Where did you first encounter Giger or his art, and how did the collaboration come about?

Well I had always seen Giger’s stuff, way back to the ’60s. Even before he was doing airbrushing, there were a couple of his black-and-white line images that were sold in head shops and were kind of standard in that milieu. And of course everybody loved Alien. It was a real cultural touchstone.

And Debbie and I were living up on 58th Street and we noticed that he was having a gallery showing shortly after he won the Academy Award that was down the block on 57th Street. So we just went by and by weird coincidence he was there, with the Oscar. But he knew who we were and we invited him back to our apartment and sat around with him and Mia, his wife at the time, and we became friends. And when we started working on Debbie’s solo record I was aware of the one or two album covers that he had done previously, so we reached out to him and he said, “Sure, let’s do the album cover.”

Is it true that the cover was banned?

In the UK they deemed it too severe to put in the Underground, in the subway. So there was a version that had a triangle-shaped crop over the face, cutting off the needles that are protruding through her head.

Giger was also instrumental in titling the album, which was a reference to the needles—“koo,” like a-cu-puncture—and a weird reference to Thor Heyerdahl’s book Aku-Aku. Heyerdahl was an adventurer who among other things took a reed boat across the ocean to replicate the ancient experience of sea travel.

Giger also produced two videos for the album—are there any stories behind those, like the sarcophagus with the blades going through it [for “Backfired”]?

It was all linked together [with the cover image]. Giger totally identified as a magician, he was like Alan Moore or Rosaleen Norton, so there’s that magical iconography going on in a lot of his work. And it just all came about at the same time, doing the videos to go with the album cover.

We went over to Switzerland and stayed with him for about two weeks in Zurich, and he had already made some of these things. He’d sent us Polaroids of this body suit that he designed for Debbie. He made these elaborate copper masks that he used as spray-paint stencils to paint her face with. They made a mold of her face as soon as we got there. It was very involved, and a lot of these artifacts are still around.

Outside of the KooKoo work, do you have any other Giger art?

I’ve got a throne from when he was going to do Dune with [filmmaker Alejandro] Jodorowsky. It’s the Harkonnens’ throne. And I have one of his airbrush paintings of New York City that he was doing around that time. His magical interpretation of New York City was that it was an inverted crucifix, because of the high-rise buildings and all the subway tunnels running across underneath.

Was there any reason for working with Giger on KooKoo? Did you see any affinities between his art and the music?

There’s a little disconnect between the weird, sci-fi aesthetic and the funky tone of the album. But after all this time, I think it works. It just seemed like a no-brainer to work with Giger.

In addition to your KooKoo books, you’ve got a memoir coming out soon. Is there anything in it about your time at the College?

There’s a bunch of stuff about SVA. I had a great time at the school. There were so many people on the faculty that went on and were really notable. Joseph Kosuth [1967 Fine Arts] was there and Alex Hay and Malcolm Morley, just on and on. I had some really inspirational photography teachers, too. Irene Stern was great.

It was the Wild West back then. . . . My friends and me found a little room in the basement on 21st Street and I had an enlarger we put in there and we had a darkroom going for probably like two years. We’d just go upstairs to the lab to get chemicals and come back downstairs. I did a tremendous amount of printing there. And in the room that this littler room was in was the circuit board for the phone lines, so we just brought a telephone down and connected it and my friend spent a lot of time talking to his girlfriend in California.

In your Visual Arts Journal interview with Johanna Fateman [BFA 1997 Fine Arts], you mentioned taking a course at SVA taught by experimental composer Steve Reich. What do you remember about that?

He was interesting. He tried to get everyone to make little modular synthesizers out of transistors and stuff. I don’t know if anybody did it. I couldn’t grasp some of his complicated rhythms. I remember trying to play cowbells with him and failing miserably.

You were very present in the ’80s art scene—co-hosting TV Party with writer Glenn O’Brien, working with Giger, and there are the famous Jean-Michel Basquiat, Fab 5 Freddy and Lee Quiñones cameos in the “Rapture” video. Did you have any interactions with any of the SVA-affiliated artists from that time, like Keith Haring [1979 Fine Arts] or Kenny Scharf [BFA 1981 Fine Arts]?

Oh yeah, I knew both of those guys well. I still occasionally run into Kenny. I have one of those boxing-match posters of Basquiat and Andy Warhol [by Michael Halsband (BFA 1980 Photography)]. I was sitting around in the last Factory with Andy and Keith, and Keith drew on it and they both signed it.

This story has gone around a lot, but I met Jean early on in his painting career. He was mostly painting on cardboard at that point and I said, “Do something on canvas for me.” He got this old piece of burlap—it wasn’t even stretched or anything. I liked militaria, so he did this line thing of soldiers shooting cannons at each other and stuff like that. I bought it for $200, and he went around and told everybody how much he’d ripped me off. And then we ran out of money and I sold it for 10 grand before he died. But nobody saw it coming, what was going to happen with the art market.

I could’ve bought all those Marilyns and Elvises and all that shit. I just took it for granted, because I used to see it every day and I was never very mercenary about that stuff. I had four of Warhol’s skull paintings, which I sold when I ran out of money over the years. But I have the actual skull that he painted for those works. I have held onto that.

This interview has been condensed and edited.