This week, the final installment of March—the three-volume graphic-novel memoir of civil rights hero and U.S. Congressman John Lewis, co-written with Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell (BFA 2000 Cartooning)—received the National Book Award for Young People's Literature. To celebrate the occasion, we are republishing an interview with Congressman Lewis, Aydin and Powell from the fall 2014 issue of Visual Arts Journal, SVA's magazine.

Nate Powell, Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Selma, Alabama.

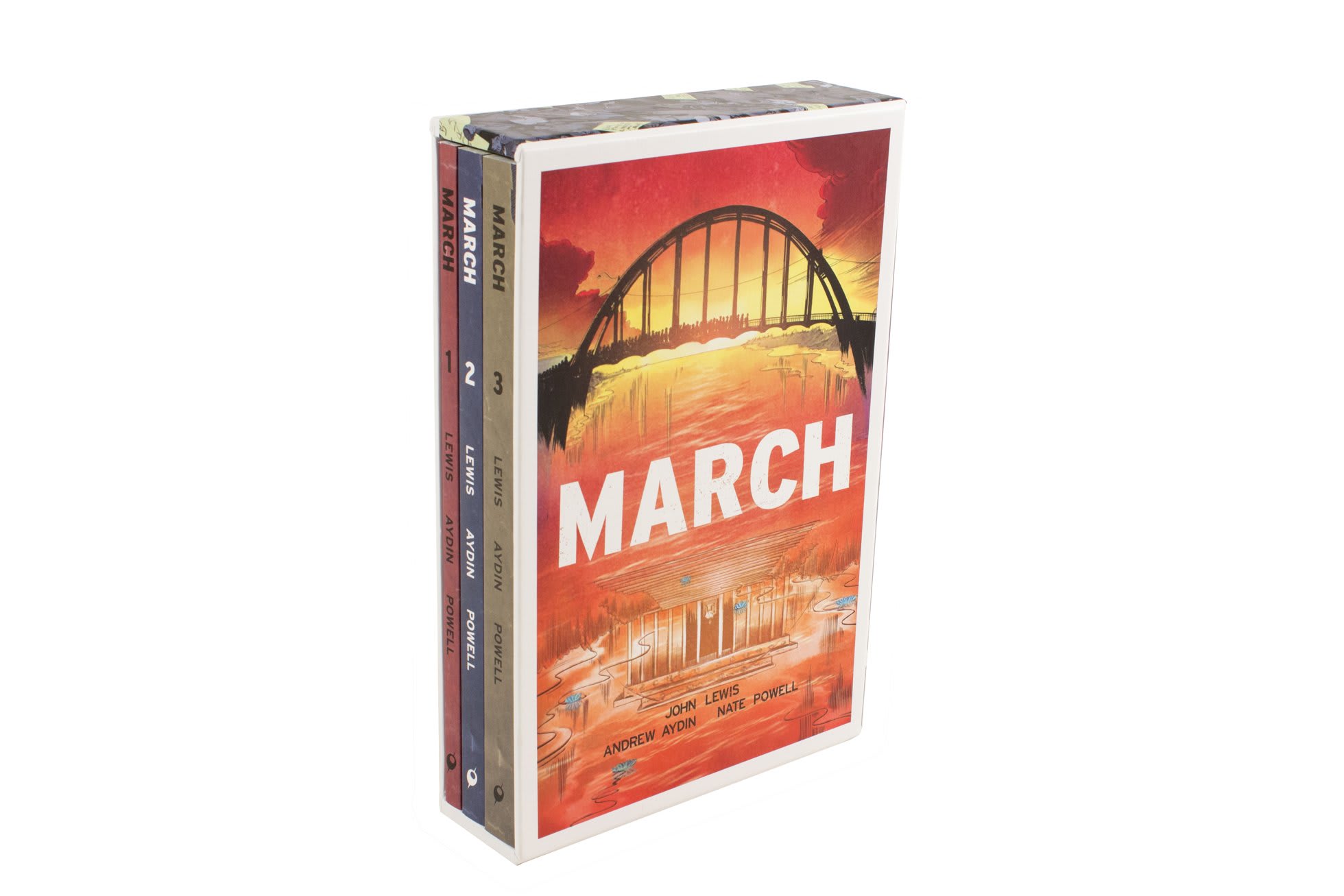

In 2013, comics publisher Top Shelf Productions released March: Book One, the first installment of a three-volume graphic-novel memoir by civil rights hero and U.S. Congressman John Lewis. Co-written with Andrew Aydin, who also works in Lewis’ congressional office, and drawn by Nate Powell (BFA 2000 Cartooning), a graphic novelist and illustrator, March is both a work of history and inspirational text, dedicated to “the past and future children of the movement.” The idea for the project, Lewis says, came from his memories of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, the 1957 comic book about the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott; the publication became a tool for teaching nonviolent activism to Lewis' generation. A New York Times #1 bestseller, March has received universal acclaim and numerous honors. To date, it has been added to public school curricula in 29 states. The second volume will be released in January 2015 and the third in the summer of 2016.

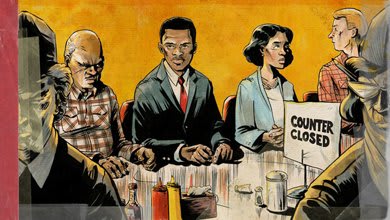

Only 23 when he became chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he also spoke, John Lewis was one of the youngest, and most esteemed, civil-rights leaders. For his unyielding commitment to acts of peaceful, nonviolent disobedience—including lunch-counter sit-ins, to protest whites-only service; “Freedom Rides” on buses, to desegregate seating; and voter registration drives, to combat disfranchisement of black citizens—he was harassed, arrested, jailed and assaulted. In 1965, on a march in support of equal voting rights, he and some 600 fellow activists were beaten and gassed by state troopers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, an event widely credited with spurring passage of the federal Voting Rights Act later that year. Lewis, though badly injured, went on to continue a life devoted to public service. In 2010, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

In May 2014, Lewis delivered the address at SVA’s commencement exercises, urging the graduates to use their talents to fight injustice. “You have a mandate,” he said, “to get out and disturb the order of things.” Shortly after, Visual Arts Journal spoke with Powell and Aydin by phone, and Congressman Lewis graciously agreed to answer some questions over email.

NATE POWELL

How did you get involved with March?

I’d worked with Top Shelf since 2005, but our relationship started several years before that: In my junior and senior years at SVA, I would send them a copy of every book that I made. [Top Shelf founders] Chris [Staros] and Brett [Warnock] were really good about giving feedback, so we developed a wonderful relationship, and they went on to publish my graphic novels Swallow Me Whole [2008] and Any Empire [2011].

A few years ago, I read the release announcing that Top Shelf would be publishing March, and that they were looking for an illustrator for it. I didn’t think about myself for the job—I had other projects lined up. Then, a couple of weeks later, Chris gave me a call and strongly suggested I try out to be the artist. So I got the script and whipped up some demo pages and sent them to Andrew and Mr. Lewis. They gave me their comments and I redrew them and sent them again, and we realized pretty quickly that something was clicking between us.

Since this story is autobiographical and the script had already been written, did you approach the project strictly as an illustrator?

It’s very much been a collaboration. Originally, March was a single, 150-page graphic novel. But within a day or two of my breaking that down according to my storytelling sensibilities, I realized we were dealing with a 500- or 600-page story. So within a few months, we all decided to break it up into its natural divisions and take our time with it. And through the process of working out Book One, I think our sense of teamwork has grown and evolved, so it’s even more collaborative now.

As a visual storyteller, I have a different kind of attention. With Book One, the major thing I brought to the narrative was changing the flow of time on the page, and extending the sections of silent narration. One example of that is the first “present-day” scene, with Congressman Lewis waking up on the morning of President Obama’s first inauguration, and just taking the time to show him getting ready for the day. That was expanded from two pages to five. Another example was John Lewis, as a child, hiding underneath his house, trying to ditch his farm work in order to go to school. Or the trip he took from Alabama to Buffalo with his uncle, driving through the segregated South—that went from two pages to five or six. Whenever there’s a moment of anxiety or dread or excitement, I like to extend it as long as possible.

Before March, had you ever drawn living or historical figures?

Well, Silence of Our Friends [a 2012 graphic novel, which Powell illustrated] is more or less a true-to-life tale. But I don’t think I’d actually depicted any historical figures until March, so this has been a real trial by fire. I think by the time the trilogy is done, I’ll have drawn 300 real, historical characters.

The first page I ever drew for March was the scene where John Lewis meets Dr. King for the first time, which was nerve-wracking to do, but sort of helped me get over that speed bump pretty quickly. With Dr. King, whose face is so recognizable, it made me realize that one stray line makes you lose the likeness. Now, every time a new person comes along in the script, I sit down and tackle them a couple of times instead of blindly charging ahead. Once I’ve figured out my visual shorthand, I try not to look at photos as much, and instead use my master drawing as reference, to keep things from looking too stale or photo-derived. For the most part, it’s just getting down the person’s skull structure. I was really lazy for a long time, particularly about cheekbones and noses.

Another thing that I’d been lazy about was accuracy with era-appropriate fashion, cars, technology. ... For March, I’ve used a couple of lifestyle and illustration books from the ’50s and ’60s, I spend a lot of time doing Google image searches, and I have a bunch of photography books of the civil-rights movement, as well as every single mug shot of a Freedom Rider.

Are you including depictions of lesser-known activists in the story?

Yes. It’s very important to me and the congressman also that this not only be a story of his life, but a story of his role within a much larger movement of people. So the fact that this is a highly visible book that covers the Freedom Rides, and there were 289 Freedom Riders who ended up getting arrested total—there’s a certain amount of responsibility to honor everyone involved. I draw the actual people whenever I’m given the chance.

ANDREW AYDIN

How did the idea to turn Congressman Lewis' story into a graphic novel come about?

When I was working on Congressman Lewis’ 2008 reelection campaign, he told me about the Martin Luther King comic, and how incredibly influential it was at the time. Being 24 and not knowing any better, I asked, “Why don’t you write a comic book?” Eventually, after asking him many more times, he said, “Let’s do it—but only if you write it with me.” That moment changed my life. Suddenly I was co-authoring a book with John Lewis—while simultaneously writing my master’s thesis on Montgomery Story, and how it had helped inspire protest movements not just in America but around the world. This medium I’d treasured for so long was now a major part of my professional life.

What was the writing process like?

Most of it was just listening to the congressman and getting his storytelling voice down on the page. I’ve heard him tell these stories to kids and parents, people visiting his office. We talked on the phone after work and got together on the weekends and recorded hours and hours worth of tapes. So much of the material is coming from anecdotes the congressman has been telling for 50 or 55 years, so there’s sanctity to the words he uses. For me, one of the highest compliments we’ve gotten for March was when one of Mr. Lewis’ oldest friends told me his favorite part was where Mr. Lewis apologizes to visitors for his desk looking “junky.” He said that was exactly something that he could imagine John Lewis saying.

Are you a comics fan?

Oh, I’ve been a fan-boy since I was a little kid. I got my first comic when I was 8 years old— Uncanny X-Men #317. My grandmother bought it off the spinner rack at Piggly Wiggly. My favorite series right now is Scott Snyder’s The Wake. I could go toe to toe with a lot of comics nerds. ...

After we sent out review copies of March, one reporter called me and said he’d given the book to his 9-year-old son to see how he’d react to it, and after he’d read it, his son put on his suit and started marching around the house demanding equality for everyone. That’s something I always knew comics could do, and it’s wonderful seeing it happen again now. Like any art form, comics can move and inspire people in profound ways.

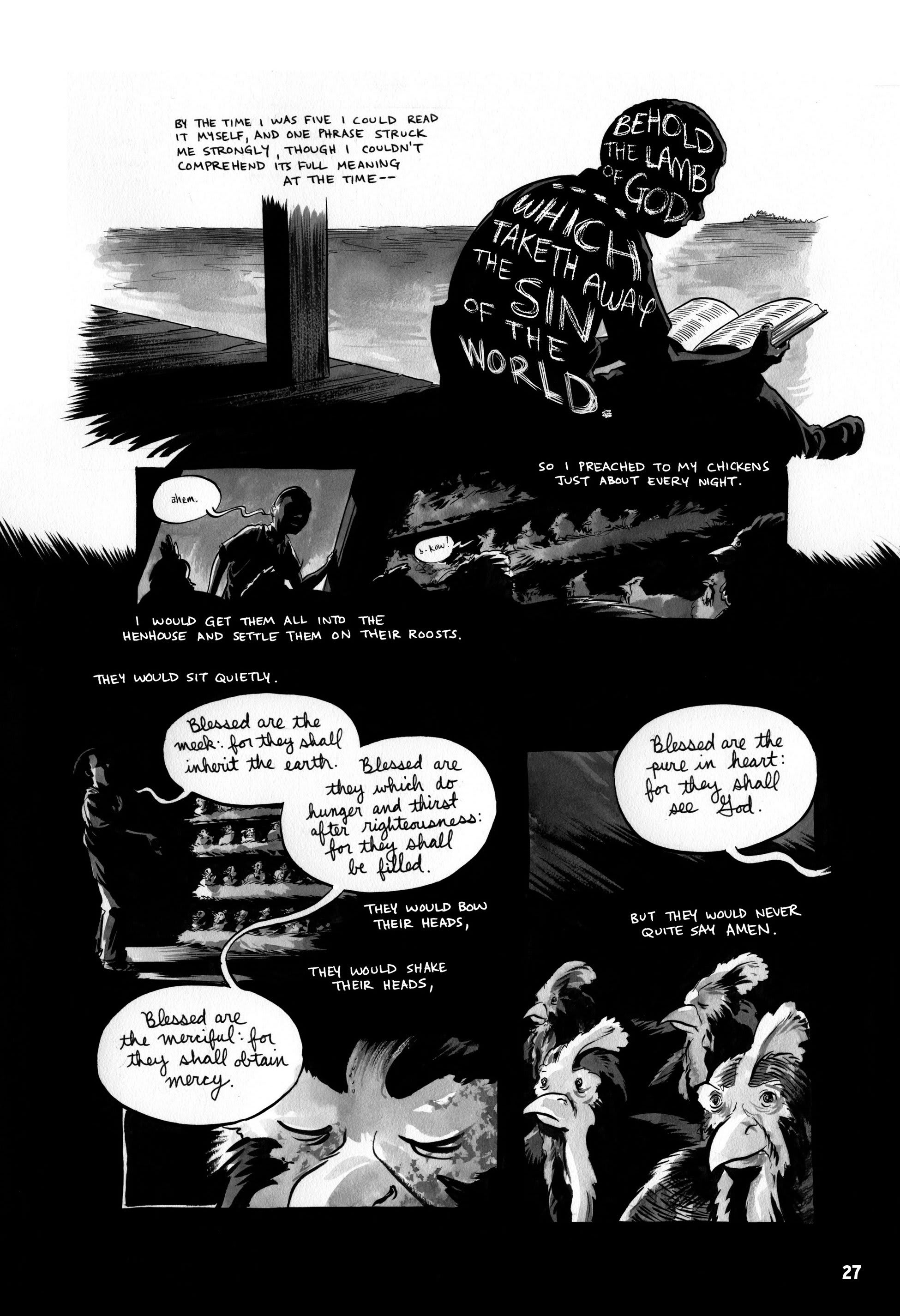

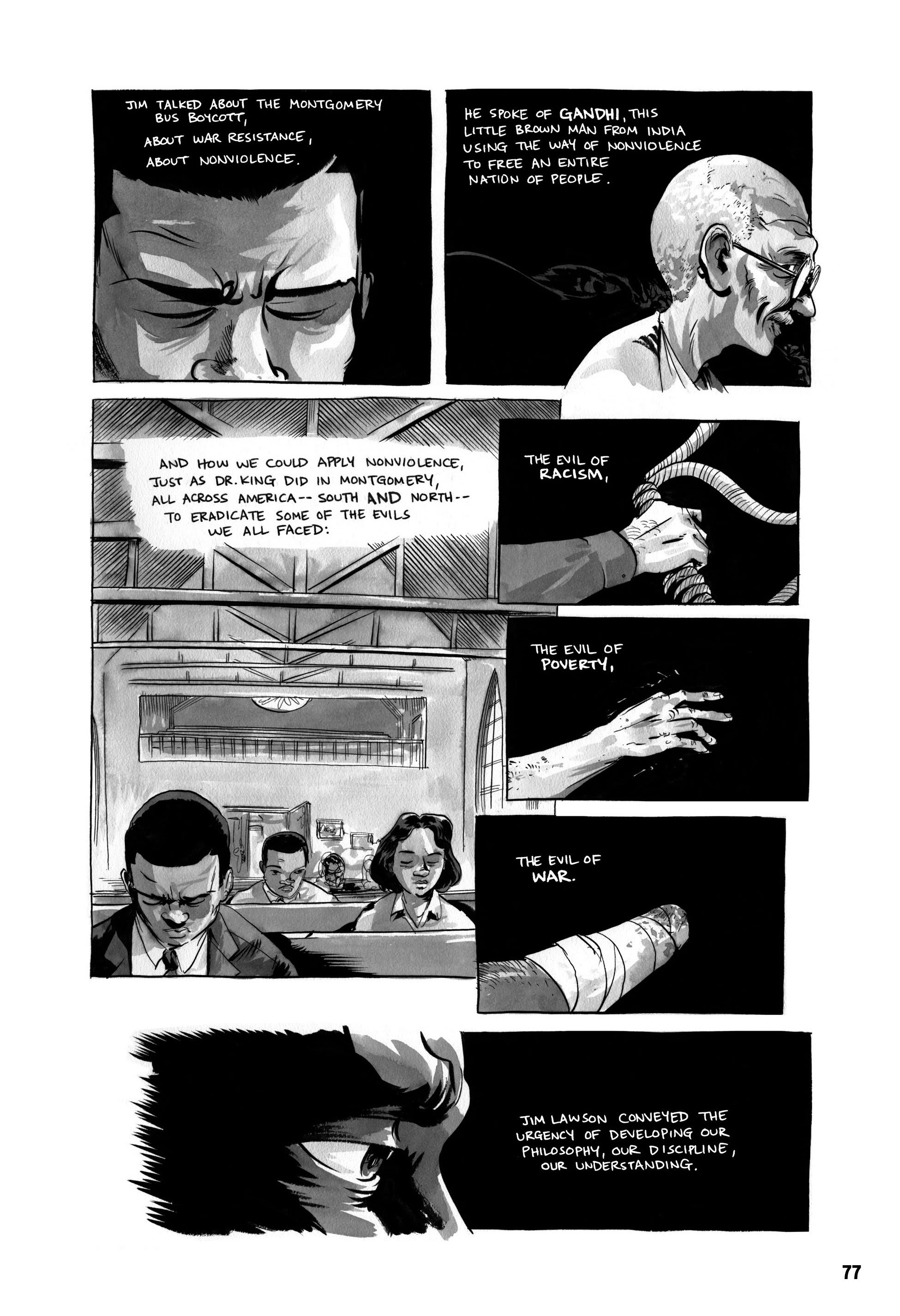

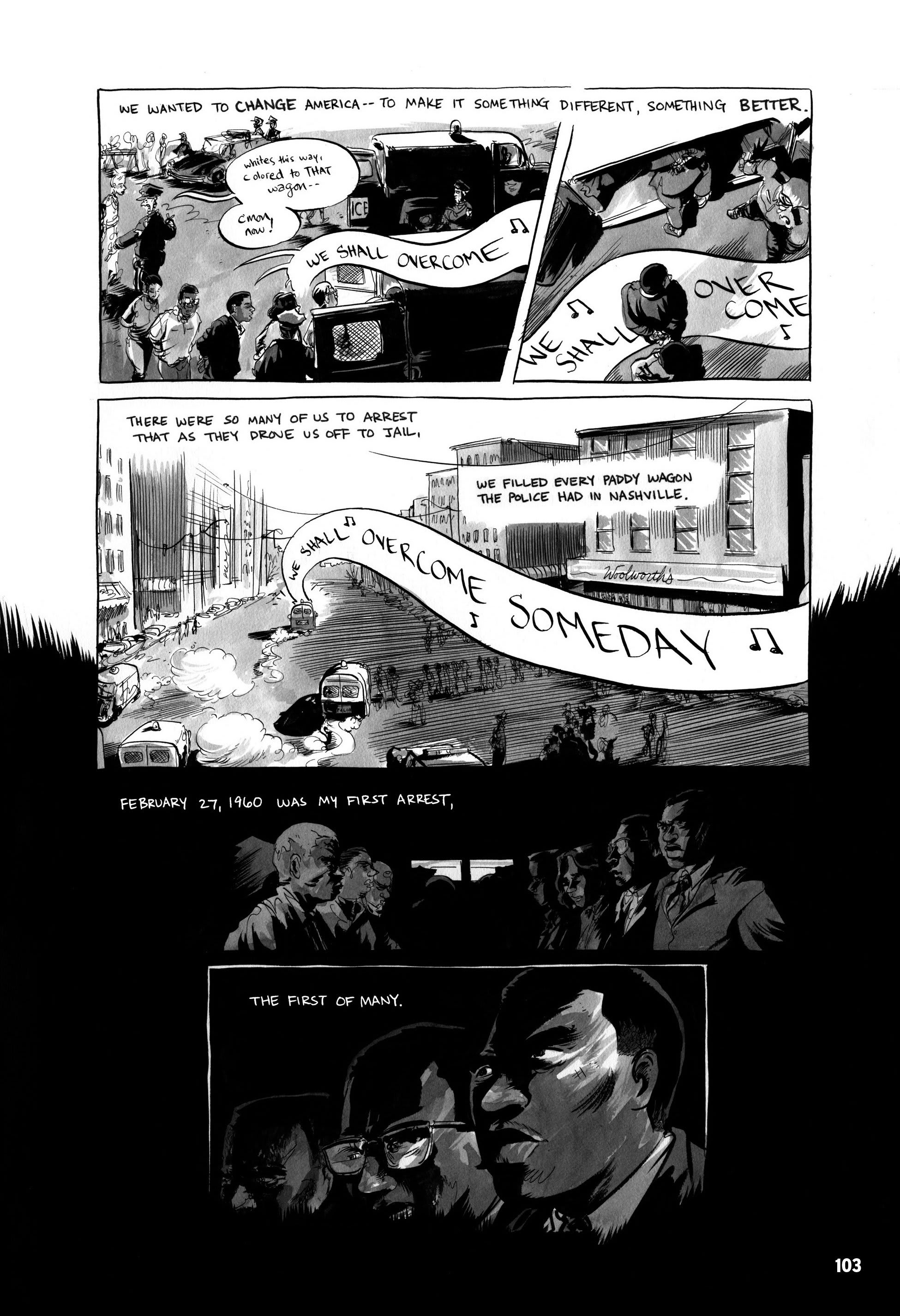

Excerpt from March: Book One.

CONGRESSMAN JOHN LEWIS

You've written about your life before, but this is the first time it's been given a graphic-novel treatment. What was it like seeing an artist's recreation of, for example, memories of your childhood?

It was very moving. I shared with Nate and with Andrew my early growing up with my brothers and sisters, my mother and father, in rural Alabama. There were never that many photographs—very few, if any, people had cameras when I was growing up. It was simple, and at times bleak, but at times very hopeful that we would be able to improve our lot. Especially when my father bought 110 acres of land in 1944 and we moved. But it was very difficult, still, for many, many years.

Early on in March, there's a section about the importance of your relationship with your Uncle Otis, who you wrote "saw something in me that I hadn't yet seen." Can you tell me more about his role in your life?

I believe my Uncle Otis did see something very special about me and in me. He encouraged me to stay in school and get an education, and he did everything to support me, including taking me on a trip to Buffalo with another uncle and my aunt and cousins. When I first went off to college, he gave me a footlocker and also a $100 bill—more money than I ever had. And he stayed in touch. His encouragement and support meant a great deal. He was very proud when I got involved in the civil rights movement, but he worried, like my mother and father and other relatives, that something could happen to me.

In your SVA commencement speech you urged the graduates to get into "necessary trouble," as you did at their age. What cause or causes would you dedicate yourself to if you were a college student or young graduate today?

I would get involved with helping to do something about comprehensive immigration reform, helping to dramatize the need to fix the Voting Rights Act, and doing something about climate change, protecting the environment—urging people to come together and plan and work together to leave this little piece of real estate we call Earth a little greener and a little cleaner and a little more peaceful.

In March, you mention drawing strength from the Bible. What other works have inspired or influenced you?

In addition to the Bible, I was moved by reading about what Gandhi attempted to do, and what he accomplished. He was going up against the British Empire, and he succeeded. He never gave up or gave in. He never used violence. He helped change India and inspired men and women all around the world. And his life and work still inspire people today.

I also remember, as a young student, being in school at Fisk University, and seeing the work of Aaron Douglas. He was one of my teachers—he taught me art appreciation. But his work inspired me, and many, many other young people. His art described life as it was during those days, and when you look at those paintings, those drawings, they are itching. They said, in effect, that it doesn’t have to be this way. They gave us hope to dream for a better day and for a better world.