Little, Brown

When Americans are finally released from the clutches of COVID-19, will they return to the deluxe department stores, boutique shops, emporiums, megamalls, shopping centers, outlets, big-box stores, and discount chains to continue where they had left off in their consumerist frenzy? While it is true that many tend to do their shopping online, there are still squadrons of suburbanites and urban dwellers eager to flood the mezzanines and return to what filmmaker George Romero called, in his horror classic Dawn of the Dead (1978) “an important place in their lives,” referring not just to addled consumers but the gaga zombies for whom the mall was the ultimate destination when they were alive.

Romero’s barb was particularly sharp, and still retains its sting. Shopping has long been a national pastime in the United States, equivalent to baseball and buddy action movies. The buying of feel-good goods fills a cavernous pit of need. It’s a peculiar satisfaction that can only be derived from useless pleasures. For just what do those consumers take home with them? Whirring buzzing soon-to-be-obsolete machines that slice, dice, mash, sliver, julienne and score, which are used once or twice before being retired into a dusty, forgotten corner. This is a phenomenon that didn’t slip past the acerbic gaze of comedian George Carlin: “People spending money they don’t have on things they don’t need.” But that never stopped anyone from calling the QVC hotline at three in the morning and ordering the do-it-yourself hot-waxing kit to melt the insignificant sprout of hair on their toes.

These items can run anyone a pretty penny. Barely make enough to cover the month’s expenses? That’s A OK, you can fork over your credit card or a post-dated check—never mind paying that gas and electric bill (who needs heat when you have the sun?). Nothing screams “American!” more than the idea of troweling on healthy debt (which makes me wonder, what’s unhealthy debt? paying down your liver transplant procedure using your Wells Fargo Platinum Card?). For the majority of Americans, it is impossible to purchase a house, let alone a car, without taking on the added financial burden of money owed, because that is the fast track to building credit. Expediency in the 21st century has been retrofitted into the American DNA. But in actuality it’s Hobson’s Choice and Sophie’s Choice rolled into one.

The U.S. Consumer Debt Crisis, which sounds like a classification in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, has risen to 14.3 trillion dollars according to the recent numbers disclosed by Forbes, and that is not solely due to the damage wrought by COVID-19. Consumer debt has been on a collision course ever since the first universal credit card was stamped in 1950. The story of how Americans have been bamboozled for more than seventy years is one that is possibly found in the Museum of American Finance, complete with ultra-boring animatronics and PowerPoint presentations more soul-killing than those famously delivered by former Speaker of the House and world-champion snoozefest Paul Ryan.

Let’s face it: money rules over our society, as Saturn rules over Capricorn. Nothing could stanch the swift circulation of cash money money money flowing on a green river. Whether it’s the writer of popular fiction who receives a two million dollar advance (while her fellow scribblers gnash their teeth in envy), the hedge-fund guru out of Greenwich, Connecticut who nets an astonishing sixty million dollar bonus, or the multinational corporation that generates one hundred and ten billion dollars in annual revenue, the broadcasts concerning the reaping of a cash harvest is served up for us nightly via the panting media, each numerical digit and each erotically placed decimal pointing to our own failure to earn such powerful sums. This is all part of the game played daily in the national arena. To have great wealth means that you’ve won the Olympic gold; to have none pegs you as an unqualified loser. This is undoubtedly a blinkered view of the world, but one that many captains of capitalism generally espouse; and it is a view that the novelist Stephen Wright, in his blow-your-mind satire, Processed Cheese, clearly despises.

This prodigiously imaginative author of four novels (which include the freakout masterpieces Going Native & M31: A Family Romance) takes as his subject in his fifth major work the same superpower in decline that he has diagrammed under x-ray for nearly four decades: the United States of America. Wright sees the U.S. as battered and seriously ill and in need of emergency surgery, so he straps it into a gurney and sends it right through the crash doors and into the operating theatre. Income inequality, unfair wages, rampant greed: Wright knows that things are just as messed up in roll-coal country as they are in the urban metropolis. Too many communities are socially fractured and divided along the electoral map. E pluribus my fucking unum!

In Processed Cheese, our (sorta) hero, Graveyard, is one of those scrappy unfortunates who is barely hanging on. Pounding the pavement in a fruitless search for employment, he is stopped short when a bag of money virtually lands at his feet, tossed from a high-rise building. Once he opens the bag and discovers boodles of cash, his life, and that of Ambience, his tough and feisty wife, becomes a fuel-injected fantasia. They are led to such prodigals of orgiastic shopping that they barely have the time to unbox all of their purchases. The newfound money, which never diminishes no matter how frantically the couple spends, bewitches them into a new modus vivendi. Their accidental wealth alters not only their conception of time—“We’re off the clock. We’re not in time anymore. We’re flying above it.”—but their perception of the world. “From now on our lives are gonna be exploding with all sorts of spooky flavors.” In other words, money is like crack-smack-and-cocaine whacked up and distributed into a pile of crushed lab-grade uppers and sucked one-shot up the nostrils using a six-cylinder blowpipe. Whew! They now live on “the far side of the money moon,” and have no intention of returning to the real world of unpaid bills and canned soup dinners. “Numbers plus or minus tend to achieve the kind of hazy delirium in which everything blends with everything else to produce a pleasing rush,” Graveyard says to his friend, Herringbone. “You know, the way it should be.”

Graveyard and Ambience, though cash-besotted, do not develop defective brains. While it is true that they begin to echo the language of the top 1 percent—“Those who deserve the money get the money”—they also grow more self-aware, even philosophical, the more money they spend. Yet, they can’t bear to part with their riches. As Graveyard points out, “the bag abides.” When we first meet Ambience, the world was bringing her down, though she couldn’t articulate why. “She just wasn’t feeling good about herself. She’d been feeling this way for a long time.” But later, supercharged by spending sprees, she arrives at this startling realization while visiting a Reptile House with a friend. “They watched live mice being dropped into cages . . . The spectacle left Ambience feeling raw and unfinished. Everything stuffing everything else into its big collective mouth. Gobble, gobble, gobble.” This is the novel’s great theme in a nutshell. The more you have the more you will want to devour—and you won’t stop gorging yourself until you drop through the bottom of the world. Why else would Jeff Bezos relentlessly pursue trillionaire status (all the while barring his thousands of “fulfillment center” workers from joining the union, which would help grant them more equitable working hours and better warehouse conditions)?

Graveyard and Ambience’s reckless spending will soon attract attention. Enter MisterMenu: “founder, president, and CEO of NationalProcedures, a division of GlobularSystems, which was an affiliate of TheConsternationGroup, a branch of ProjectileStrategies, which was a wholly owned subsidiary of Divinicon, which owned everything.” As unsavory a tycoon as your run-of-the-mill parking garage king, MisterMenu is also the husband of MissusMenu, who in a fit of rage hurls the bag of money over their balcony. And now MisterMenu, a powerful man who really has no need of the lost cash, wants it back. For that he will enlist the assistance of his most deadly operatives, BlisterPac and DelicateSear, to retrieve the cash at all costs.

From this simple set-up Wright has managed to create a subversive work (how many novels put America square in their gunsights and pulls the trigger?) without bursting a blood vessel. The narrative does not advance in a frenetic pace, and the tone never reaches a high pitch. In fact, all is cast in a consistently mellow vibe, as if to narcotize the readers and toss them into the same groovy boat as the characters. Through them Wright nails many a contemporary malaise. We can understand how Ambience, experiencing a bad case of the hurries, feels as if “a secret sender hack[ed] into her system an endless stream of malware to make her sick.” How many of us suffered a grief of mind after being overwhelmed by the rapid pulse of information pumped through our eyeballs daily? And what about our relationship to money, which has become so debased that when Graveyard wallpapers his penis in Founding Fathers, perhaps we’re not too surprised to find him entering such an excited state? (This bit of hilarity is followed by a single page in which the word MONEY is blazoned on every line, the chapteral equivalent of Faulkner’s famous “My mother is a fish” in As I Lay Dying)

In the person of MisterMenu, we see the emptiness and queasy grandiosity of a man glutted with too much wealth, striding about as if he had accomplished the equal of Washington crossing the Delaware. This is a man to whom the Stoic doctrine of the World Soul or the Kantian notion of a designed universe means absolutely nothing, for ex officio he sees himself as The Creator, all earth beginningless until his birth. As Christopher Moltisanti says of the boss of his family, Tony Soprano, in The Sopranos: “He thinks everything belongs to him.” This explains why MisterMenu would wish to retrieve a mere bag of money when he already has all that he needs and then some.

Is this arrogance familiar? It may be too pat to say that he is reminiscent of Trump, who has no true beliefs, allegiances, or morals, except when it pertains to himself. But Trump, like MisterMenu, maintains a bulletproof heart, one that has been calcified to one purpose and one purpose only: the preservation of power. This is what makes both men dangerous. (Trump himself is like the hands of a clock untethered from the bolt, who will turn in whichever direction the winds of time blows most favorably, even if this spells the destruction of the republic he is sworn to protect. Every time I snatch even the merest glance at him on a television I could feel my inner Fahrenheit drop).

Additionally, MisterMenu’s perversity knows no bounds, judging from the suis generis chapter wherein he seduces a young woman into playing a black-hearted game which I will only say involves a shitload of money, a bucket, and a strong digestive system. The young woman finds herself in an original house of bondage, which serves as a nifty metaphor for the workaday world. The question asked in this set piece is an important one: how much are you willing to cram down your throat in order to earn your pay? The answer left me with a desolate feeling, as on the morning of a funeral, when all the house lights are on but within you it is total flailing darkness.

It is fascinating to note that there are no recognizable brand names in this novel, and I think the purpose is twofold. Wright does not want to serve as a promotional shill for any corporations (a thought which would surely gladden the heart of Naomi Klein, author of the immortal book No Logo and arch-enemy to brand consultants worldwide), which is understandable, since this novel is a scathing critique of consumerism and an examination of money rot. But another reason lies in the tired quality of the famous products themselves, which are given wraparound names that attenuate the power of the very thing from which they are derived (Nike, for instance, is the winged goddess from Greek mythology who personifies victory, though I’d bet that most of us can only think “sneaker” when the brand is mentioned). Huxley, in A Brave New World, gave us Soma; Orwell, in 1984, had Victory as his brand of choice; but in Wright’s zany world the products blaring from the shelves are as multifarious and overwhelming as they are in reality. Ladies wear Loubotomy fuck-me stilettos. A bottle of water is GlacialEuphoriaReserve. People sit in the shade of popcorn trees and sip goosenut water while admiring paintings by Wisenheimer and Mucilage. Consumerism for the well-heeled is conducted in The TooGoodForYou District (Wright is very funny), where there are “shops, not stores”—in other words, nothing could be bought on layaway and nothing is half-off the selling price.

Naturally, in keeping with satire, Wright’s wholly invented world is meant to mirror our own. The characters in his novel are recognizably human and thoroughly contemporary. Graveyard’s father, Roulette, is a lifelong member of “the Frightened White Man’s Flying Freedom Freedom Party,” which is no different than the GOP. Farrago, Graveyard’s sister, attends a Consumer Heroes class in a school that was founded by “Old White Guy.” Her boyfriend is Loophole, who engages in a convincingly rendered and steamy affair with the brother of Farrago and Graveyard, SideEffects. Sex and drugs are prevalent, as are the wild and woolly trips.

Every character, as you will have noticed, is unusually named, and this is in keeping with Wright’s ravenously consumerist world. As corporations wish for us to embody the spirit of their products and abide by their messaging (I’m casting back to a Gap campaign, where subway commuters were told to “Mind the Gap” via the PA system, and they were so grateful not to be dragged under the wheels of a moving train that they developed a sudden hankering for pegged jeans), the characters in the novel have been branded, and their names, much like logos, express their personal identities in this world. Consider MisterMenu, whose name implies a wide variety of choices. His vast wealth affords him an untold amount of privileges, and it is he who sets the order of the day at his leisure. But if we were to consider our own lives, and the daunting amount of selections at our fingertips when we contemplate, say, our Netflix queue, can this not put the pause on our activity, and essentially paralyze us because of our wealth of choices? This is disconcerting to contemplate, because there is truly a too-muchness in our lives that induces anxiety.

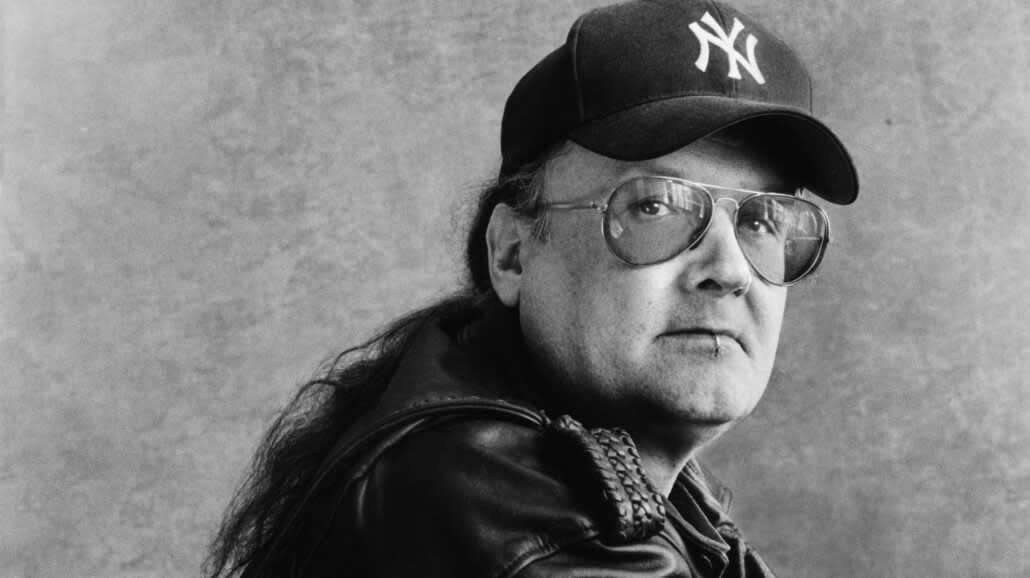

Stephen Wright

There is no writer quite like Stephen Wright. He has been compared to those po-mo stalwarts, Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo. Yet, even though Stephen Wright can pen a sharp comedic line, he doesn’t indulge in extended scenes of burlesque or scatological humor, like the great Pynchon; and though his characters are often paranoid and his narratives front-loaded with irony, his writing is distinct from DeLillo’s brilliant, deadpan surrealism. Wright’s style is far more mordant, the prose expansive, the language often hallucinatory, and the characters more believable as human beings as opposed to just being vehicles for ideas. The tone of his characters’ dialogue, when veering from the naturalistic, can take on philosophical heft (the characters sometimes seem surprised at their own reserves of intelligence, as we are sometimes surprised by our own). There’s nothing of the cookie-cutter plotting, and the lines hammered to flat perfection, that I find in many younger novelists. It’s as if they send their works out into the world with their faces washed and their ties knotted and their shirts tucked in. That’s why so much of it bores me. It’s like one of those persistent and familiar songs you hear when you’re shopping for avocados, you know, the ones that seemingly take the peak-seat on the list of the Supermarket Top 20 and spend hours colonizing your brain.

Though the writing in Processed Cheese is often as spare as his created world demands, this is a departure for the novelist, who is capable of prodigies of prose. Take this neo-mythical and surreal description of a new bride from Going Native: “The miraculous budding of her face, renewed cheeks bright as the flesh of raw petals, ritual’s signet pressed into living tissue for all to mark and know once again the vivifying power of ceremony, the repetition of right word and gesture opening a circuit in the aisle of time, eternity’s proof in the turgor of the heart.” “Turgor,” an amazing word, is the risky marker of a writer who lives comfortably at the outer edges. This is why Wright is often dubbed “a writer’s writer.” Measure his prose on a gold weight scale and the amount in grams would confound all calculations. There aren’t many writers today who would even hazard such prose, for fear of declining sales. But as Cormac McCarthy wrote in his chilling Southern Gothic, Child of God: “More’s the fool.”

Edwin Rivera is the Editor of The Match Factory and a Writing Instructor at the School of Visual Arts. His first play, In the Palace of the Planet King, was produced at the Wild Project theatre on May 9th, 2019, as part of the Downtown Urban Arts Festival.