The art of Peter Svarzbein (MFA 2011 Photography, Video and Related Media) imitated life to such a degree that his life now imitates his art. As a city councilmember in El Paso, Texas, Svarzbein is overseeing the reintroduction of an electric trolley line that ran through the city and across the border into Juarez, Mexico, from 1902 to 1974. In 2018, the old track—complete with the original streetcars, restored with modern amenities—will reopen for public use on the U.S. side of the border. The $97 million endeavor, funded by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT), is a result, in part, of Svarzbein’s 2011 MFA thesis project at SVA.

Svarzbein had wanted to do a project that blurred the lines of conceptual, fine and performance art. He also wanted to express his identity as a border resident. The light went on in 2010, when a Google search yielded an image of the defunct streetcars. Svarzbein, an El Paso native, had never heard about them before and was intrigued. Employing his skills as an editorial and commercial photographer, he created an advertising campaign to promote a fictional El Paso-Juarez streetcar line, with collateral featuring a character named Alex, the trolley’s conductor and “the border’s newest hero.”

On trips to El Paso during his thesis year, Svarzbein wheat-pasted his trolley posters onto walls and hosted pop-up events to build faux awareness. After graduation, he moved back to El Paso to turn make-believe into reality. He began collecting signatures to add a real trolley initiative on a 2012 bond measure. Though unsuccessful, his efforts caught the attention of TxDOT, which included the project in a $2.2 billion multimodal transportation package.

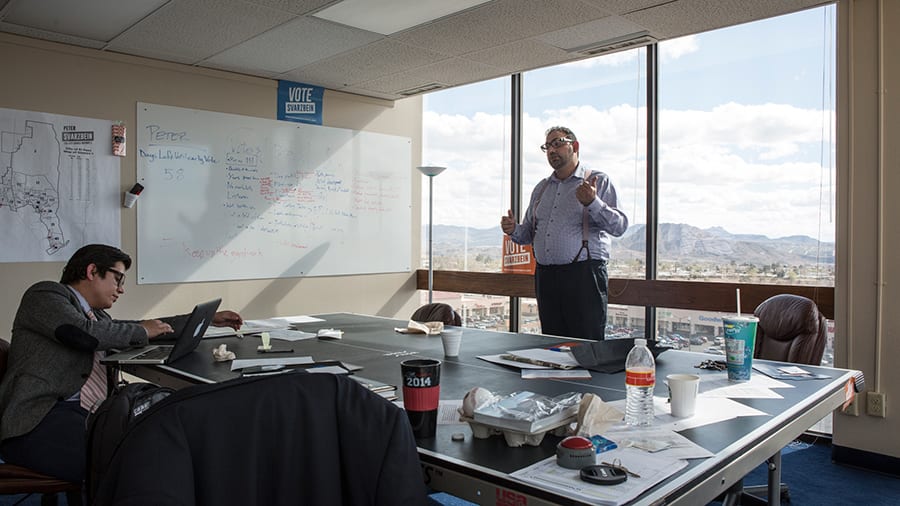

Svarzbein continued to invest his creative equity in El Paso. He served on a board to reimagine the city’s historic San Jacinto Plaza and he began teaching at the local outpost of the Texas Tech University College of Architecture. Inspired by his community, Svarzbein ran for and won a city council seat in 2015. He is learning how to navigate bureaucracy and plans to run again in 2019. After all, he has business to finish: reconnecting the line all the way to Juarez and destigmatizing the act of border crossing.

Why were you inspired by the old streetcar image you found online?

The trolley is a beautiful metaphor for what it means to be from El Paso and the region. Border crossing defines us, from the richest of the rich to the poorest of the poor. We have 80,000 people a day who cross the border. And we have 80,000 people who cross back at the end of the day. This is not illegal immigration, it’s not people going off into the distance. It’s people who are waking up every day to work in El Paso, or who live in El Paso and have a series of veterinary clinics and they drive over every single day to work in Juarez, and then they come back to El Paso. That’s the reality. And that’s what’s not understood within this larger conversation we’re having about border security. Border security for us here is being able to have goods and people—human capital, with their ideas and their investments—cross the border in a safe and efficient manner. That’s our challenge and opportunity.

What was the scope of your thesis project?

I recorded a series of video ads that imagined this bored guy and girl in El Paso. And they’re like, “There’s nothing to do. . . . Oh, let’s go take the trolley [to Juarez].” And all of a sudden the conductor magically appears. And then I created these posters of over-the-top, militantly positive ideas, concepts and sayings—“Let Us Take You Home on Either Side of the Border,” “The Future Is Arriving on Time on the Border Again”—as a way to imagine something better. And that was kind of it: if we’re going to have something better for the border, we have to imagine what that can look like. It’s sort of utilizing the framework of an ad campaign to talk about these real issues. And it confused people because this was, like, 2010, 2011. In 2010, more people were killed in Juarez than were killed in all of Afghanistan. So there were a lot of puzzled faces like, what are you talking about, going to Mexico?

How was the thesis received by SVA?

I had one instructor who could not understand the concept. She could not understand why you would want to have a border that people would want to cross because for her, borders are there to keep people out. They’re not things to play with. They’re not things to cross. They’re not places that create a third way, where you’re neither here nor there. And I think one of the most fascinating things about El Paso is that it is that third space. The entire U.S.-Mexico border is that. But when I presented at the review committee, my instructor started clapping. She said, “I really had my doubts. I thought you were biting off a lot more than you could do. All I can say is dream as big as you want to because you’ll figure out a way to make it happen.”

Donald Trump says he’s building a wall between Mexico and the United States. Is it realistic to think the trolley will ever reconnect to Juarez?

To me that’s the biggest opportunity. I’ve placed legislation already to look into doing a feasibility study for a passenger-oriented, multimodal transportation system. The question becomes, what makes most sense? Is it a vintage streetcar line? Is it a new pedestrian-only bridge that has a shuttle light rail in between it? When we talk about how you go and make the most for a 21st-century economy, you have to be able to have people cross the border in an effective way. If Trump is a businessman, he should understand that there is value in this region from an economic point of view, and that if you want to talk about security, border security is tied into economic security and opportunity. If you want to cut down on the influence of cartels, the best way to do it is by providing good jobs and creating more infrastructure and more economic drivers. If I could get five minutes alone with him, that’s what I would discuss.

Do you miss being an artist?

I’m still struggling that I have to give up one for the other. I never thought that at 36, I’d be running for this and at 40, I’m running for this. I don’t know what exactly the next steps are. I would continue teaching if I could, but the city charter does not allow employment through two public institutions. But I still have a gallery downtown, Purple, which I own and run. I still photograph. I have a 10-year project I’ve been working on: Latino families who believe they’re descendants of Spanish Jews who had converted to Catholicism under King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. Have you ever heard the term “crypto-Jews” before? I photographed religious conversions back to Judaism in Santo Marta, Colombia; in Mexicali, Mexico; in Santa Fe, New Mexico; and in El Paso and Odessa, Texas.

How did being an artist equip you for politics?

The thing that was serendipitous for me, politically, was that I . . . had people who knew my family or knew me. And also I had been a big advocate for civic engagement and the arts through different downtown initiatives, as well as the trolley, since I got back. I think having that combination helped me.

But at the end of the day, I think that an artist is able to see the world not as it is, but what it can be. Politics is a medium the same way painting, sculpture or photography is one. There is a certain set of rules that apply within that medium. Rules are meant to be broken, too, but there are certain ways that a medium works that you need to understand and sort of work within.

Michael Hoinski is a regular contributor to Texas Monthly and The New York Times. He lives in Austin.

A version of this article appears in the spring 2017 issue of the Visual Arts Journal.