A Conversation on Spirituality, Cultural Tradition, and Ritual Art

Honoring loved ones through ritual is a cultural and spiritual practice for many on Día de Muertos, including artist and SVA MFA alum Paulina Mendoza Valdez. To kick off the construction of a community altar in the Flatiron district celebrating Día de Muertos, we talked with Mendoza-Valdez about creating altars for public and private practice.

Attendees were invited to leave mementos and ofrendas at Mendoza-Valdez's altar for the deceased on the final day of the holiday, November 2, in Flatiron North Plaza. For more information about the event in partnership with Flatiron Nomad and contributions from Materials for the Arts, visit Eventbrite.

What inspired you to take on this project?

PMV: I have been working on setting altars on Día de Muertos in different public spaces for the last couple of years. Being someone who has moved a few times, the altars have been a way to introduce myself to others while inviting them to participate in a tradition bigger than me. The big difference is that my past installations are personal reinterpretations of Día de Muertos, whereas this altar is meant to be presented in the most authentic way possible.

How do you begin to create a ritual altar, be it for Día De Muertos or another occasion? How does knowing that an audience will be viewing your altar affect how you create it, as opposed to creating a personal altar?

PMV: Día de Muertos is celebrated worldwide and was officially declared part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2008. A modern-day Día de Muertos altar serves as a way to commemorate the dearly departed and invites them to the “land of the living” for a night. Altars can be viewed as a bridge that connects the past to the present as they are often rooted in rituals rich in historical and cultural context but can also include an individual’s familial traditions. Each personalized altar is typically set up every November 1st and 2nd and may include photographs of the deceased, along with their favorite food, drink, toys, and any other earthly delight they’d probably enjoy having again for a night. These delights are called ofrendas–things we offer them for visiting us.

The physical space that an altar occupies also impacts how it is dressed and approached. An altar placed in a public space such as this one will hopefully serve as an invitation for people of all backgrounds and beliefs to participate in this celebration and learn about the uniqueness of each altar and its purposeful components. Furthermore, it may spark curiosity to learn more about Mexican history beyond how it is depicted and celebrated in the United States.

To build a personal altar, I’d begin by examining one's intimate history and how that connects to certain tools. I believe in seeking out other resources to connect to if the religious practices you grew up with are not enough for you. Nevertheless, it is important to do your own research and be knowledgeable of the practices you’d like to tap into and make sure that you’re learning from the sources. There are some closed practices that need to be respected or approached in a much more specific way.

Día de Los Muertos altar by Paulina Mendoza Valdez.

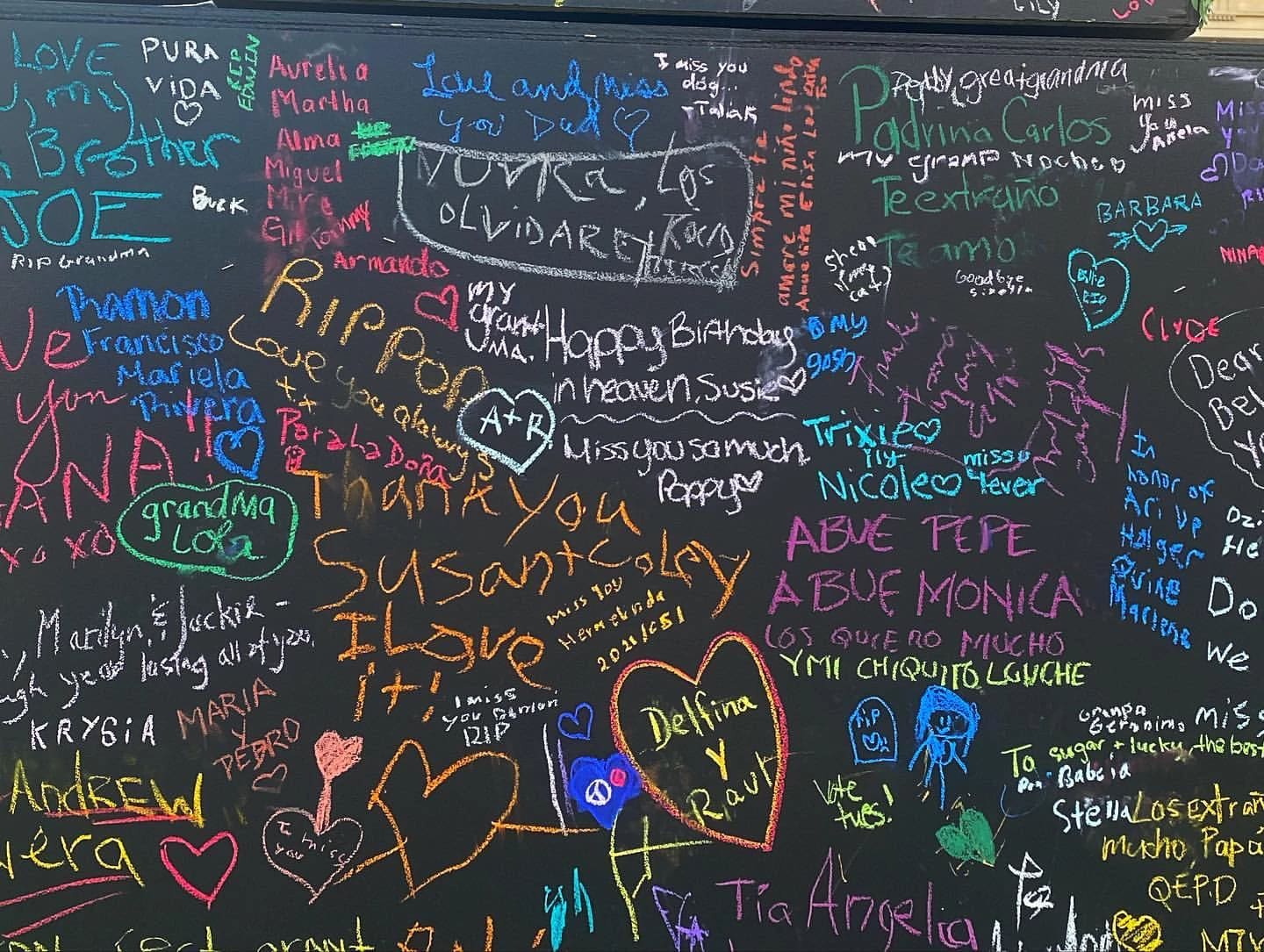

Community contributions to the Día de Los Muertos altar in the Flatiron District.

Community contributions to the Día de Los Muertos altar in the Flatiron District.

On Instagram, you mentioned that one of your interests during your SVA MFA program was in exploring blending your spiritual upbringing with building self-preserving and healing communities through art. Can you share a little more with us about how your spirituality and culture intentionally inform your art practice?

PMV: For the past two years, I’ve been using altars on an art platform to re-reinterpret a centuries-old tradition. As much as Catholicism was embedded in my upbringing, it never fully took over my own personal moral code. After a series of events, I started to intentionally seek something bigger than me. Right before coming to SVA, I audited a class with Dorota Biczel, “Global Modernisms”, where she talked about the colonial movement and the takeover of “Art” over cultural aesthetics. It was around the same time when I was intentionally seeking something bigger than me, so that class pushed me to research the colonial history of my own traditions, look into my family’s practices, and locate my own position between these two. My work has always been about questioning intimacy and what it’s like to relate to each other on a personal level; now I get to ask questions about how we relate as different communities in the same space.