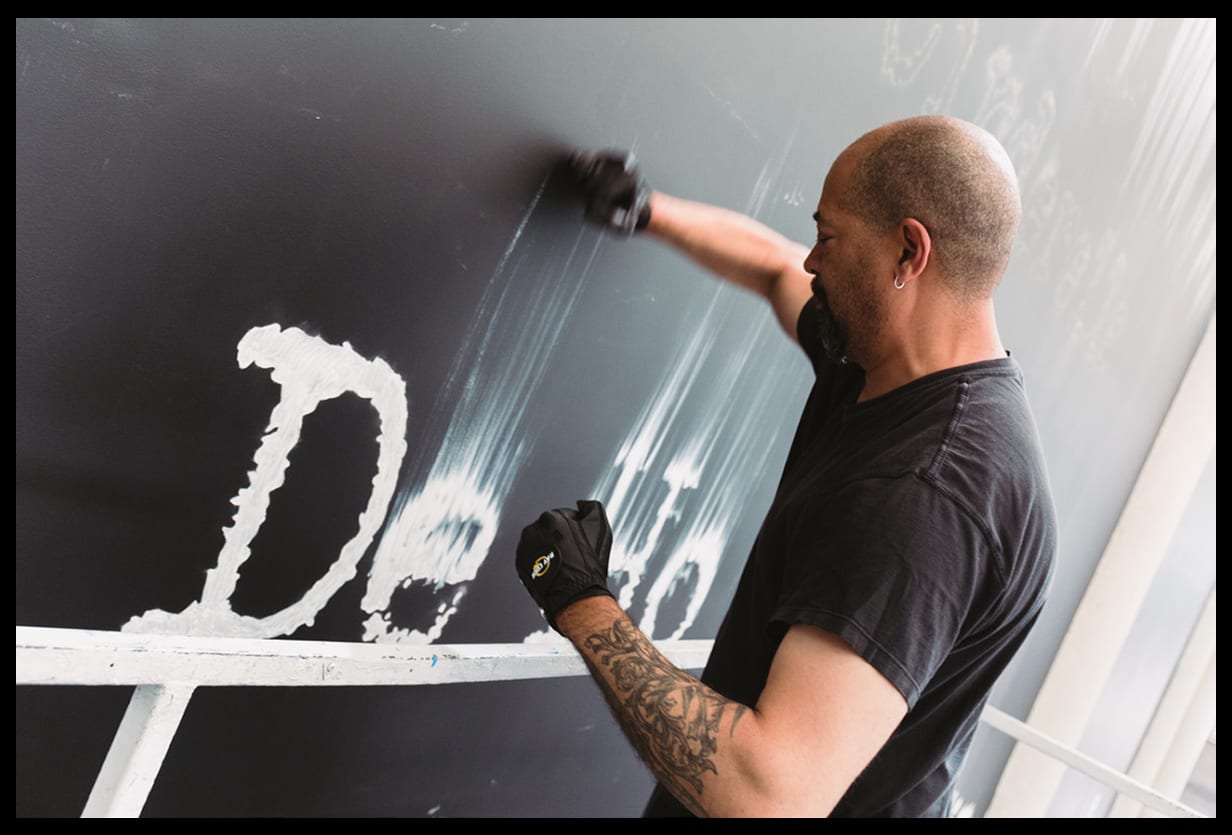

Gary Simmons works on "Fade to Black," his 2017 – 2018 installation at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. Photo: Tito Molina/ HRDWRKER. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Not long ago, Gary Simmons (BFA 1988 Fine Arts) went to see his daughter in a children's theater-group play. Partway into the production, one of the actors forgot her line. Everyone on stage froze, unsure of how to continue. The audience froze, too. "The whole room is this pregnant pause," Simmons says. "We're all sitting there going, 'How's this going to end?'" Finally, another performer made a silly gesture. "Everybody started laughing, and the scene closed right there," he says. "That kid saved that scene. Not by saying something, but by doing something. It was the most honest moment of the play. And it's those kinds of things, in art, that you're after." It’s late May and we are sitting in Simmons' studio, a large and simple space in a nondescript section of Los Angeles. Canvases destined for upcoming exhibitions at the Baldwin Gallery, in Aspen, Colorado, and the Simon Lee Gallery, in London, are on the walls. Each has been painted to look like something between a dusty blackboard and a flickering black-and-white film. The compositions are layered: Racist cartoon characters from early animations appear as though they have been traced in chalk dust, while bold white texts—naming old, largely forgotten movies and African American actors—are stamped in the foreground, in big typewriter-style letters. The bleary quality of these works is a signature element of Simmons' practice, known as his "erasure" technique. Simmons has been making erasure drawings and paintings for so long, he says, that he can now reference himself when he makes new ones. These latest paintings tie together some of his earliest and most recent experiments with the method. The texts are a continuation of newer works like "Fade to Black," a 2017 – 2018 installation at the California African American Museum that celebrated little-known figures and films in early black cinema. And the cartoons call back to his first erasure drawings, from the early '90s, when Simmons was just out of graduate school. Done in chalk on blackboard or surfaces prepared with slate paint, they isolated characters, objects, even lone physical features from 1930s and '40s animation, to expose the ways that even something as seemingly innocent as children's entertainment can employ and inculcate bigotry. Black Chalkboards (Two Grinning Faces with Cookie Bag) (1993), for example, shows two floating smiley faces, leering at a bag of cookies. The works were widely acclaimed, but Simmons soon moved on to more enigmatic subjects.

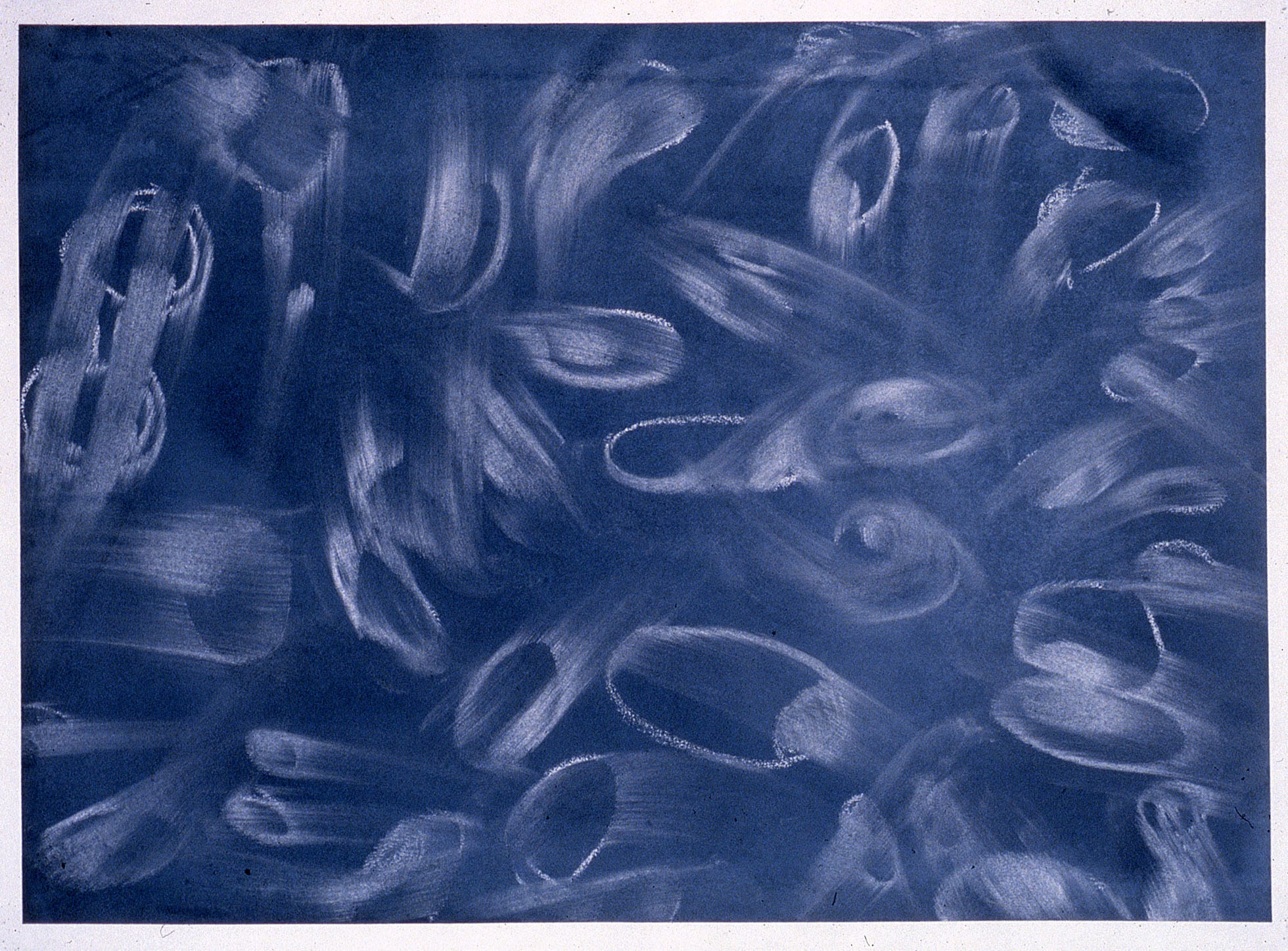

Gary Simmons, Study for Wall of Eyes (Cartoon Bosco), 1993, chalk on paint. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

"When you're young, you kind of bounce from thing to thing and you never totally get done," he says. "And I was working on this film-based stuff and thought, 'I don't think I'm done with these cartoons yet.' … I've always loved them, they've always been attached to me, so I started to sheepishly bring them back, little by little. Now they're back, and it's like an old friend."Simmons has been a working artist for nearly 30 years, making sculptures, installations, drawings and paintings that investigate the capacity of symbols, make totems of everyday architectural objects, reveal the ways racism is knitted into culture and evoke the haunting and imperfect nature of memory. The bulk of that time has been divided between New York City and Los Angeles; he swears this last move, which happened about two years ago, is permanent. ("We were in New York," he says, "and one day I was like, 'You know what? I'm done here, man. Let’s move to L.A.' My wife was like, 'Are you insane?'") He has taught at Yale, SVA, the University of Southern California and the California Institute of the Arts, also known as CalArts, and is represented by galleries in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and London. His work is the subject of three monographs and countless articles and reviews, and in the collections of more than 20 institutions, including the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, The Museum of Modern Art in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Born in New York City, he grew up there and just north of it, in suburban Rockland County, as the son of West Indian immigrants. He was a skilled baseball player in his teens, and his father, a fine-art photography printer and devoted Dodgers fan, encouraged him to pursue it as a career. But then his knees started to go, and he turned his attention to what he really loved, which he calls "making stuff." High school was an unhappy time for Simmons, who was bored and subjected to the racism of classmates and teachers. After graduation, he moved back to the city and, at the suggestion of a former art teacher, enrolled at SVA. After graduating, he did a residency at the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture, in Maine, then drove across country for the MFA program at CalArts. Like New York, Los Angeles was a different city then. Before GPS, Amazon and Uber, something as basic as buying materials could take a full day of driving. Simmons says he could spot his fellow out-of-towners by seeing who else was pulled over on the shoulder, paging through a road atlas.

Gary Simmons, The Stadium, 2013, enamel on panel. © Gary Simmons, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Simmons is full of praise for the teachers and mentors he found as a young artist: at SVA, Douglas Crimp, Joseph Kosuth (1967 Fine Arts), Jack Whitten and Jackie Winsor, among others; at CalArts, Michael Asher, John Baldessari, Catherine Lord and Mike Kelley ("probably the smartest artist I ever met in my life"). His undergraduate and graduate experiences were complementary, he says. Where the prevailing approach at SVA was "make stuff, and then think about it," at CalArts students were taught to "think about stuff, think some more, then think it through again, and then make it.""It was pretty cool to have both," he says. "I think that really made me who I am." (It also gave him an appreciation for the importance of serving as a mentor to less-established artists. "He has followed the unspoken contract of his responsibilities to his assistants above and beyond," says Angela Conant, MFA 2013 Art Practice, who worked in Simmons' studio for several years before enrolling at SVA.)Post-MFA, he returned to New York and began his career in earnest, supporting himself by assisting other artists, hanging art in galleries and museums, and working the odd renovation job, often with a crew of fellow up-and-comers, including painters John Currin, Sean Landers and John Zinsser. Simmons started out as "an object maker," creating austere, immaculate-looking sculptures and installations for which everything "had to have a reason for being there." He credits this rigor in part to advice he once got from Jackie Winsor: "She once said, 'Gary, we should be able to roll this sculpture down the hill, and anything that falls off is completely meaningless. The sculpture is the object at the bottom of the hill.'"Much of his early work attacked the ways that educational institutions can perpetuate inequality and enforce control. Pieces like Disinformation Paragraph and Eraser Chair (both 1989) cast common classroom objects like blackboards and erasers as tools that could as easily be used to confuse and subjugate as to teach. Others, like Six-X (1989), for which he hung six child-sized Ku Klux Klan outfits from a schoolhouse coatrack, were more explicit in their indictment.

Gary Simmons, Six-X, 1989, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

If Simmons drew at all then, it was as a way to think through his concepts. The turning point came with Pollywanna?, a piece that he first put together for a 1990 exhibition at the White Columns gallery in New York, then reproduced the following year for a gallery in Santa Monica. Pollywanna? consisted of a blank chalkboard background, a podium with a microphone, and a live cockatoo, which perched at the lectern and screeched whatever phrases it had been taught, just as educators might unthinkingly pass on lessons that they learned by rote. "It was hilarious," he says, but he was distracted by an unplanned aspect of the piece: The bird's flapping white wings, set against the matte black of the board, left illusory traces in their wake. "It was this kind of cinematic effect," he says, "these weird trails. I thought, 'Wow, that's incredible. I've got to get that in my work.'" At that time, his studio was in a former vocational school in Manhattan, in a room filled with old blackboards. He began experimenting with racist caricatures from old children's cartoons that he had drawn on the boards in chalk—preparatory sketches done for a never-completed film project with a friend. "I realized if you made a mark, there was no real way to erase that mark," he says. "Any attempt to erase this stereotype left a ghostly trail behind it," similar to the traces left by the cockatoo's wings. This partial erasure combined with the unsettling subject matter to make a work that illustrated how early, formative impressions may become clouded over time, but are never unlearned. Moreover, depending on how he moved his hands across the chalk—or, with later pieces, the charcoal, pastel, wax or paint—the images could be made to perform, in a way: spinning, burning, falling down, radiating, dissolving, flying."It's amazing to watch him do it—there's something bravura about him," says Simon Watson, a curator, dealer and consultant who mounted an early exhibition of erasure works in Manhattan. "Gary is a master of site-specific drawings and paintings. They connect with everything from Sol LeWitt [1953 Illustration] to phantom projections of cinema. They're stunning works." "The drawings are so well made, but they're almost the antithesis of what we think of as a good drawing, because they're willfully unfinished," says Amada Cruz, director of the Phoenix Art Museum, in Arizona. "They're a metaphor for how memory works, and they're also very evocative. As you look at them, you start to recall your own history with the subject matter. They're about serious things, but they're playful at the same time." In 1994, Cruz, who was then at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, in Washington, D.C., organized Simmons' first solo museum show as part of the Hirshhorn's "Directions" series.

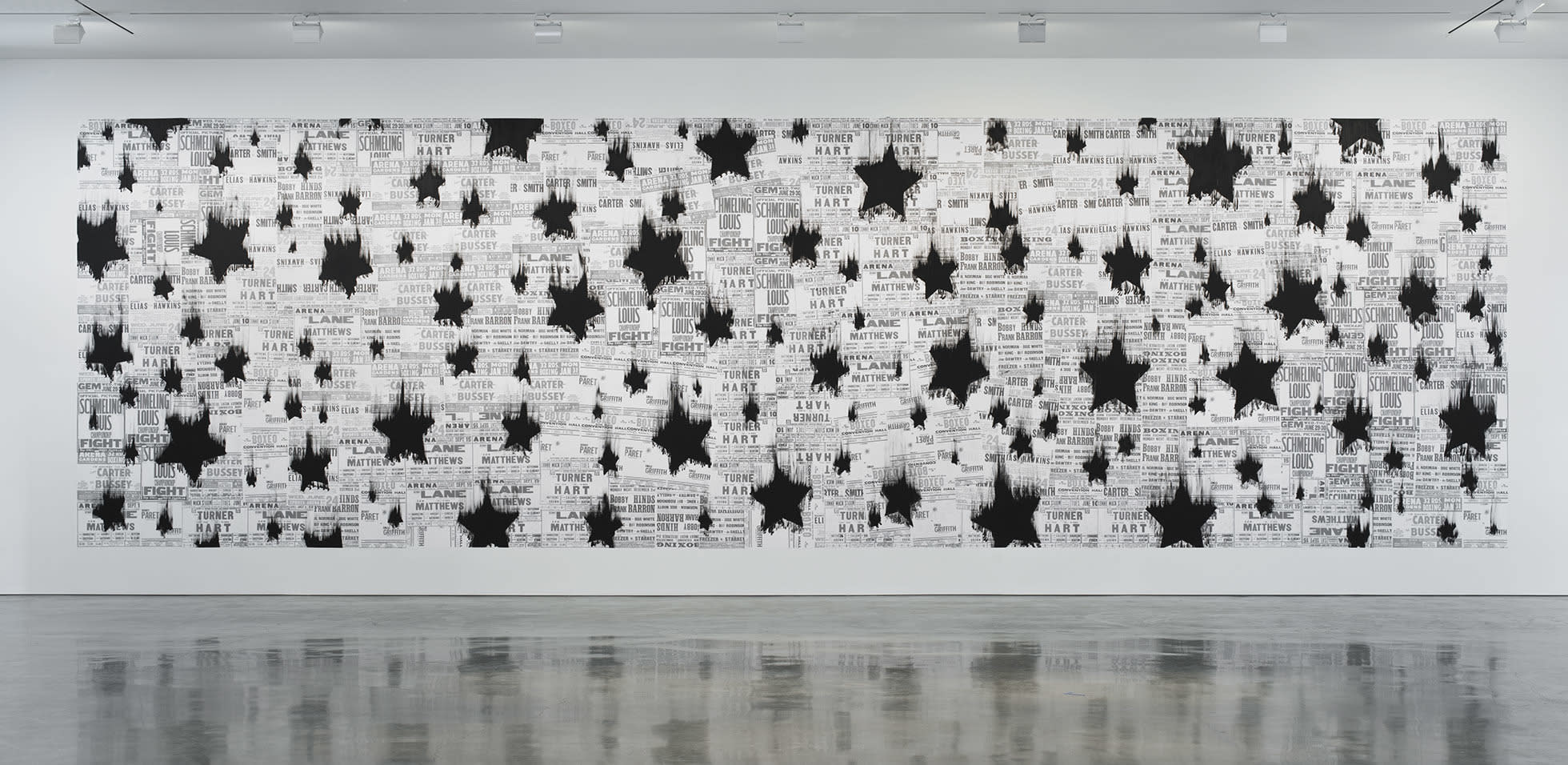

Gary Simmons, Black Star Shower, 2013, oil on paper applied to the wall. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

Wall of Eyes, made for the 1993 biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art—regarded now as a pivotal moment in recent art history—is arguably the most significant of Simmons' early erasure drawings. A constellation of blurred cartoon eyes on a slate-painted wall, it debuted at the exhibition along with Lineup, a sculpture in which several pairs of gilded sneakers were set in front of a police backdrop. Both works took advantage of a common motif in Simmons' work, the absence of figures, daring the viewers to fill in the blanks and, by doing so, confront their own prejudice and complicity.By the mid-'90s Simmons began to depict widely recognizable things that have multiple, dreamlike meanings: roller-coasters, grand ballrooms, gazebos, clock towers, 19th-century ships, speeding trains, swaying pines. For a 1996 group exhibition that Cruz put together at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Simmons worked with a skywriter to draw giant, ephemeral stars in the city's sky—erasure works on an enormous scale. Reflection of a Future Past (2009), a permanent work for New York-Presbyterian Hospital, is a doubled image of the skeletal remains of the New York State Pavilion, an architectural leftover from the 1964 World's Fair, in Queens. Blue Field Explosions (2009), installed in the Dallas Cowboys' oddly art-filled stadium (the building also houses a work by former faculty member Mel Bochner), shows a pair of comic-book-like combustions. This shift in focus, he says, was motivated in part by his overseas audience's narrow interpretation of his earlier work. "I started to realize that maybe the imagery was anchored to an American experience, and if I opened up this notion of erasure to architectural things, or vacant spaces that people were familiar with, it would create an avenue for people to access on their own terms, with their own cultural references. ... Everybody has a relationship to a gazebo. There is a class component to what a gazebo represents, from culture to culture."

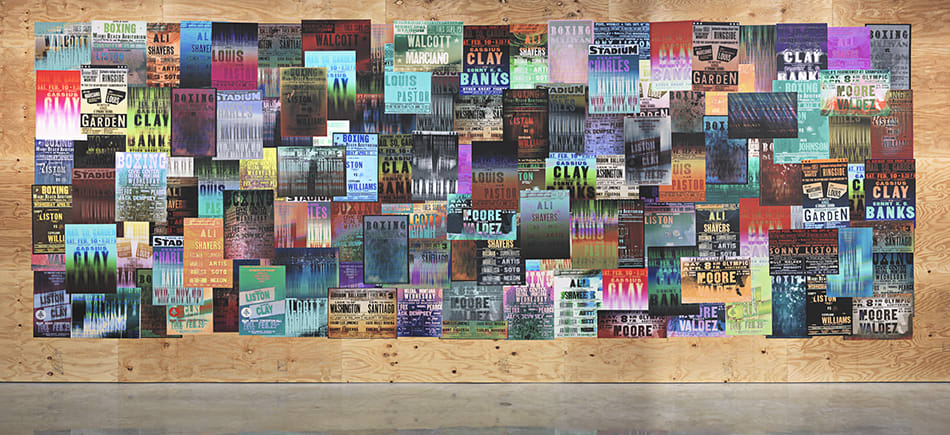

Gary Simmons,

Untitled

, 2014, ink jet posters on CDX plywood. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

In interviews, Simmons, a devoted music fan, has compared his working method to that of a DJ: Take preexisting things, drop them into new contexts and manipulate their form. References to music—and in particular its politically charged, DIY subcultures—can be found throughout his work, but he has recently been paying direct homage to his inspirations. In 2016 he created rooms wallpapered with altered reproductions of dub, hip-hop and punk concert posters for installations at the Anthony Meier Fine Arts gallery, in San Francisco, and for Detroit's annual Culture Lab event. Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark, a stack of speakers housed in scavenged wood and named after legendary producer Lee "Scratch" Perry's similarly homemade Black Ark recording studio, served as both a sculpture and the sound system for performances in New Orleans in 2014 and in San Francisco in 2017.Another touchstone influence is his time as an athlete, which he says conditioned him for the exertion and resolve that his art requires. Even today, no matter how large the size of an erasure work, he does all of the image manipulation alone and in one go. In this way, the pieces double as vivid records of the labor that went into making them. "He is very connected with his process and materials—a sculptor at heart," Angela Conant says. "After larger paintings or wall drawings, he would be exhausted."But if there is any one major inspiration for Simmons, it is film. An avid moviegoer—"I'm one of those guys that sits through the credits," he says—he has cited a childhood viewing of The Wizard of Oz (1939) as the reason he became an artist. He has made sculptures based on the hillbilly caricatures of Deliverance (1972) and paintings referencing the science-fiction feature Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972). He is voluble on his fellow artists' forays into directing: Among other things, he is a booster of Johnny Mnemonic, his friend Robert Longo's largely unloved 1995 feature, starring Keanu Reeves. And though he is wary of dilettantism, he has lately been considering using the medium itself in his work."Using film as part of what I do makes sense to me," he says. "Early on I was so locked into these specific pockets: I never used color. I never used figures. Everything had to have a significance and a meaning. It all had to have a reason for being there. That's limiting, in a way. I think you have to loosen the reins up."

Gary Simmons, Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark, 2014, wood stage, PA speakers, monitor. Installation view, "Prospect.3: Notes for Now," 2014, Treme Market Branch, New Orleans. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

For more information on SVA's BFA Fine Arts program, click here.

A version of this article appears in the fall 2018 issue of the Visual Arts Journal.