The SVA alumni of the synth-pop band The Book Of Love look back.

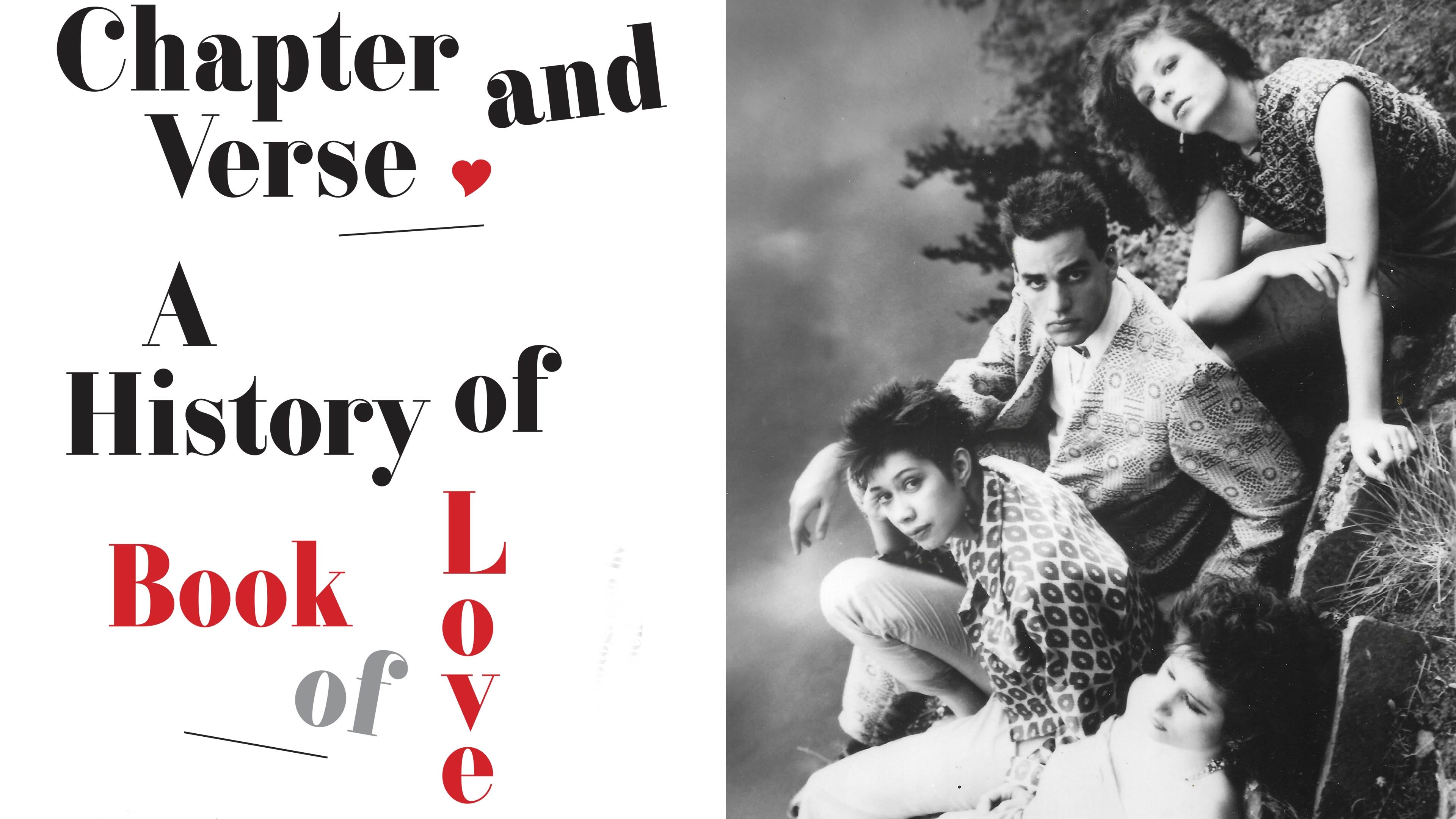

The Book of Love band, featuring SVA BFA Photography alumni Ted Ottaviano and Lauren Roselli Johnson.

In the early days, Book of Love members Ted Ottaviano, Lauren Roselli Johnson (both BFA 1983 Photography), Jade Lee and Susan Ottaviano (no relation to Ted) would have a regular Sunday rehearsal, after which Johnson and Ted would go out clubbing. The band—a synth-pop quartet whose propulsive, romantic songs would make them a dance-floor mainstay in the late 1980s—was still unknown, and New York City nightlife was at one of its storied zeniths. Legendary spots like Danceteria and Area were playgrounds for self-expression, and the post-punk and new wave scenes radiated with the energy of the new.

The music industry is famously capricious; even the most well-deserved success stories hinge on moments of good fortune or fate. Book of Love, by its members’ own account, has had several, and a big one happened on a Sunday night out at the Pyramid Club, a favorite haunt of theirs. Johnson had brought with her a demo of one of the band’s latest songs, “Boy,” a driving, minimalist number in which Susan, Book of Love’s frontwoman, sings about being denied entry to a men’s-only bar and, more universally and arrestingly, the fictions associated with gender. ”It’s not my fault that I’m not a boy,” she protests.

Johnson gave the tape to the club’s DJ, Ivan Ivan, who had just begun scouting talent for music executive Seymour Stein, co-founder of the Warner Music Group label Sire Records, home to such acts as The Cure, Madonna, The Pretenders and Talking Heads. When Ivan played “Boy” for Stein, the story goes, the executive agreed to release the song before it even got to the chorus. The single took off on the dance charts, and the band was signed to a deal and soon joined label mates Depeche Mode on tour. In little more than a year, Book of Love had gone from begging friends to come see them at a small club to opening for one of the era’s biggest bands in front of 20,000 people at the Palais Omnisport in Paris.

A photograph taken from the cover of the 2001 album I Touch Roses: The Best of Book of Love.

The early 1980s were “such a fertile time for New York,” Ted says. “I felt like I was a student by day and this creature of the night in these clubs. People wax poetic about that period because it really was unparalleled in many ways.”

Ted and Susan grew up in Stamford, Connecticut, where both of their families were part of the city’s large Italian American community. “It wasn’t clear whether we were related and how we were related,” Ted says. “It was always this weird thing”—an early bit of kismet. The two were high-school friends and connected through a shared love of music, occasionally jamming together on the Farfisa organ at Susan’s house. Ted’s big album, then and now, was David Bowie’s Low (1977), the first release in the star’s so-called Berlin trilogy and a radical departure from his earlier, more traditional pop and rock songwriting and instrumentation. At first, he found Low’s strangeness off-putting—“I used to separate it and keep it in a different place than my other records,” he recalls—but in time, it became his creative lodestar. “All roads lead to David Bowie,” he says.

After high school, Susan enrolled at the Philadelphia College of Art, while Ted joined another hometown friend, John Dugdale (BFA 1983 Photography), in applying to SVA, but the two Ottavianos’ musical collaboration continued long-distance: When Susan formed a post-punk band with classmate Jade Lee, Ted contributed songwriting and the group’s “intentionally raunchy” name, Head Cheese. (“My father owned a deli,” he explains.)

Ted also wrote music on his own, occasionally bringing his musical efforts into his photo and art classes for critiques, where he found a receptive audience.

“They understood, in a weird way,” he says of his instructors and classmates. “Even though you had a major you were concentrating on, if you were going to exist in the current fabric, you had to be open to being ‘multimedia.’”

After graduating from PCA, Susan and Jade moved to New York City, starting Book of Love—named for the 1957 song by doo-wop group The Monotones—with Ted. He would become the group’s primary songwriter; he and Lee would play keyboards; Susan would sing. “I had this idea for a new sound,” he says—a more synth-based music, built with “simple and naïve” parts and lyrics that were “like nursery rhymes.” But it was not until Johnson was added as a third keyboardist a few months later that the band fully gelled.

“We were looking for a fourth member and I remember saying, ‘Lauren’s perfect for the band,’” Ted says. He and Johnson had gotten friendly through seeing each other in class and the clubs, and she was always interested in hearing about his music. “I think we just hit it off,” he recalls. “Lauren just radiates, and we just had so much in common in so many different ways.” But he didn’t know if she even played an instrument when he asked her to join. As it turned out, she didn’t.

Johnson grew up in northern New Jersey, an artistic child in a supportive, academically inclined family. As a teenager she loved music—mainly classic rock and singer-songwriters like Jackson Browne, due to her older siblings’ influence and the prevailing local radio formats—but “never thought it was a possibility” that she would be a musician herself, she says. “Music held such a special and sacred place in my life.”

After enrolling at SVA and eventually moving to New York City, Johnson immersed herself in the local scene, digging through East Village record stores and going out dancing. “I was on my own for the first time with no curfew,” she says. “As long as I made it to my class in the morning, there was nothing to keep me from staying out until two in the morning.”

For her early parts in Book of Love, “I was assigned easy-to-play parts, like bell lines and chord-pad parts,” she says, and the Casios the band played were “toy-like and fun to play with.” She also sang backing vocals—that’s her whispering the song’s title on “Boy”—and in time would become skilled with the early Akai S900 sampler, which she would use to record sounds, like a toy cash register or xylophone, that the band would then incorporate into their music.

Book of Love rehearsed in a former morgue on Mott Street, a “scary, dark and dank” location with “strangely good acoustics,” Johnson says, that was popular with underground acts at the time—pop-rock group Wygals, the thrashers in Helmet, and psychedelic noise outfit Butthole Surfers all made appearances in the space. (The building now houses luxury condominiums.)

“You could go down there at, like, two or three in the morning and just work,” Ted says. “Nobody knew where you were or could hear you because you were in this sub-basement.”

After about a year of diligent woodshedding, Book of Love recorded their demo for “Boy” at Noise New York, a rundown studio in midtown Manhattan. There, in another piece of good fortune, Ted unearthed a dusty old set of tubular bells, or chimes, an instrument that had long intrigued him both for its appearance in “I Could Be Happy,” a 1981 single by Scottish band Altered Images, and how the sound recalled the church music of his Catholic upbringing. Inspired, he played the chimes for the song’s hook, and their anachronistic, vaguely religious quality thereafter became integral to Book of Love’s work—the group would even go on to record a cover of Mike Oldham’s “Tubular Bells,” made famous as the theme for the seminal horror film The Exorcist.

“Those bells are as responsible for our career as our whole play with gender,” Ted says.

“We all grew up with church hymns and Christmas carols,” Johnson says. “I think that has always been manifest in Ted’s songwriting and informs his way of hearing.”

Book of Love’s self-titled debut, released in 1986, was a “classic first album situation,” Ted says, “where we ended up having a few years to write and write.” The album sleeve features band portraits by Michael Halsband (BFA 1980 Photography), whom Johnson had come to know through the late SVA faculty member Walt Silver. Book of Love’s songs showcase Ted’s knack for folding evocative lyrics into danceable, melodic arrangements, and the production, by Ivan Ivan, has a quintessentially 1980s sound—all echoing synth, pulsating beats and low, breathy vocals, ideal for sweating among strangers in a dark disco.

“I Touch Roses,” the album’s centerpiece and a gnomic ode to self-empowerment, has come to be the band’s trademark song and remains Ted’s proudest moment as a songwriter. “It’s our mini-masterpiece,” he says. (Johnson, though she has other favorites, too, agrees.) The springy “You Make Me Feel So Good” became a surprise hit on Texas radio, earning the group a sizable following in the state. And “Modigliani (Lost in Your Eyes)”—a hopeless-love song that later featured on the soundtracks of the zeitgeisty TV series Miami Vice and the John Candy–Steve Martin comedy Planes, Trains and Automobiles—started another Book of Love motif of working art-school references into the band’s music and visual presentation.

“We ended up utilizing our art school influences like crazy and [Amedeo] Modigliani was an artist that we all loved,” Ted says. “Patti Smith, who we just idolized, wrote ‘Dancing Barefoot,’ which was inspired by Modigliani’s mistress, Jeanne Hébuterne. So we thought it would be great to write our own song about Modigliani, and the difference was it would be kind of a dance song.”

After another stretch of touring, Book of Love released their second album, Lullaby (1988), which they made with the British producer Flood, recording in New York and mixing at Berlin’s Hansa Studios, where David Bowie had finished Low two decades prior. Flood, who had worked with Depeche Mode, New Order and U2, brought a new level of technological sophistication to the band’s process—particularly, Ted says, in his understanding of how to best integrate their combination of digital and analog sounds. “I’d arrived in the studio feeling like all of the songs were fully realized, but he was able to open them up and take them into this technicolor place.”

The cover of Lullaby features a sepia-toned image of a cherubic child with white dove wings, created by Victorian-era photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. “I was basically going through my own personal exorcism in my first few years in New York,” Ted says, “so that album had a lot of religious themes.” The record opens with “Tubular Bells”; immortality and amulets abound on the rap-sung oddball track “Witchcraft”; for “With a Little Bit of Love,” the band recorded a part on the organ at Manhattan’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

The album’s most enduring song, however, is the jittery “Pretty Boys and Pretty Girls,” in which Susan sings of forbidden, gender-agnostic desire and alludes to the AIDS crisis at a time when the disease was still heavily stigmatized:

Strangers in the night

Exchanging glances

But sex is dangerous

I don't take my chances

The track was catchy enough to be chosen as a single, but the band, who had experienced the loss of many friends and loved ones to the disease, refused to sideline or soft-pedal its message. They declined an opportunity to license it for a soft-drink commercial and filmed a video for the song that ends on a screen reading “FIND A CURE.” While doing the promotional rounds, they made an appearance on Club MTV, an American Bandstand–type series. The production taped the guests for several days’ episodes in one block; Book of Love’s turn immediately followed one by The Ramones, who were heroes of theirs. (Lee and Ted got to meet frontman Joey Ramone, who was “such a sweetheart,” Ted says.) In a post-performance interview, Susan fields a question about the song’s meaning.

“We wanted to deal with the issue of AIDS,” she answers, earnest and halting. “We wanted to do what we could to show that we care.”

The Book Of Love.

The group’s third album, Candy Carol (1991), was suffused with a growing sense of loss as the AIDS epidemic raged on, though superficially it was their brightest-sounding record yet, a collection of songs that paid homage to their shared love of 1960s pop, the sound of their childhoods. After what had been a rushed process to write Lullaby, Ted again took his time honing the material, and songs like “Alice Everyday” and the title track signaled a sonic turning point for Book of Love. But the times were changing as was, inevitably, the state of popular music. After a fourth album, 1993’s Lovebubble—an adventurous, eclectic range of material that includes a cover of Low’s “Sound and Vision” and the chilly, electronic “Salve My Soul”—Book of Love decided to go on an indefinite hiatus.

“We didn’t realize how we were going to be identified with the ’80s until the ’90s hit,” Ted says. “The way music trends go is you need to push away the previous trends in order to forge forward.

“It wasn't until the millennium that there was a new appreciation for what we had done.”

Book of Love performing in San Francisco in 2013.

Book of Love performing in San Francisco in 2017.

Sometime after Lullaby, Johnson was working a side job in the Metropolitan Museum of Art when she ran into acquaintances of hers, film director Jonathan Demme and his wife, artist Joanne Howard. The couple were new parents, and Johnson offered to babysit sometime, to give them an occasional night out. They took her up on the offer, and soon Demme—an avid music fan with a habit of putting friends and favorite artists in his projects—cast her in a small role in his next movie, The Silence of the Lambs, playing the friend of a serial killer’s victim who is interviewed by Jodie Foster’s character, FBI trainee Clarice Starling. (The film also features “Sunny Day,” one of the rare Ted-fronted Book of Love songs, on its soundtrack.) Strange good fortune had struck again.

In the waning days of Book of Love and after the band’s initial retirement, Johnson would go on to appear in Demme’s Philadelphia (1993), Beloved (1998) and 2004 remake of The Manchurian Candidate. She married, worked for fashion designer Daryl K and became a mother. Lee pursued graphic design. Susan went to culinary school and found work as a food stylist, recipe developer and visual artist. Ted continued in music, remixing songs by artists like Hole (“Malibu”), David Byrne (“Wicked Little Doll”) and Fleetwood Mac (“Landslide,” for which the arduous process of getting access to the original tracks was “like having the Ten Commandments sent to my house,” he says). He also taught and lectured on production at such institutions as Case Western Reserve University (in collaboration with the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame), New York University and Long Island University. The four remained close, all staying in or around New York City.

In the early aughts, Book of Love released a best-of compilation, featuring three new tracks and new band photos by Ted and Johnson’s former classmate Frank Ockenfels 3 (BFA 1983 Photography), and its warm reception—Spin called it “crafty twee keyboard punk”; Time Out called it “irresistible”—heralded a revival of interest in their music. The group played some shows together, and a few years later Ted and Johnson began writing and recording together again as The Myrmidons, a side project created for a new era of synth and electronic pop.

“Lauren was good friends with Lori Lindsay, who was in this group The Prissteens, so she ended up being our vocalist for these tracks,” Ted says. As with Book of Love, The Myrmidons developed something of a cult following. They released a handful of singles, the covers of which, as with Book of Love’s discography, were designed with particular care—a testament, Ted and Johnson say, to their experiences at SVA.

“You really had to know what you were trying to do, and how well you were reaching your goals,” Ted says of his years at the College. “I felt like all those skills that we learned, we were utilizing in the music business. It sounds strange, but we really were.”

By the turn of the last decade, Book of Love was performing live again with some frequency, though usually as either a duo, comprising Ted and Susan, or a trio, with Johnson joining in—Lee, though still involved in the band, was disinclined to resume steady touring. In 2016 the entire quartet embarked on a 30th-anniversary tour and released MMXVI, another greatest-hits compilation, with two new tracks; an EP single, All Girl Band, followed in 2017.

Since then, Ted and Susan have continued to perform, with the entire group getting together for occasional reunion shows. A more comprehensive career survey, The Sire Years: 1985 – 1993, came out in 2018. Live appearances have been on hold since the onset of the pandemic but Ted hopes to get out on the road once more when the situation allows. “Our audience is so loyal to us,” he says. “The music has really been this sort of soundtrack for them.” And while the band’s present-day efforts are mostly toward tending to their unique legacy, he hints that Book of Love still has another chapter to write.

“We’re all still in touch and talk a lot, and I think we all agree that we’ve got one more big project left in us. But what that is or what shape that will take, I can’t say just yet.”

A version of this article appears in the spring/summer 2022 Visual Arts Journal.