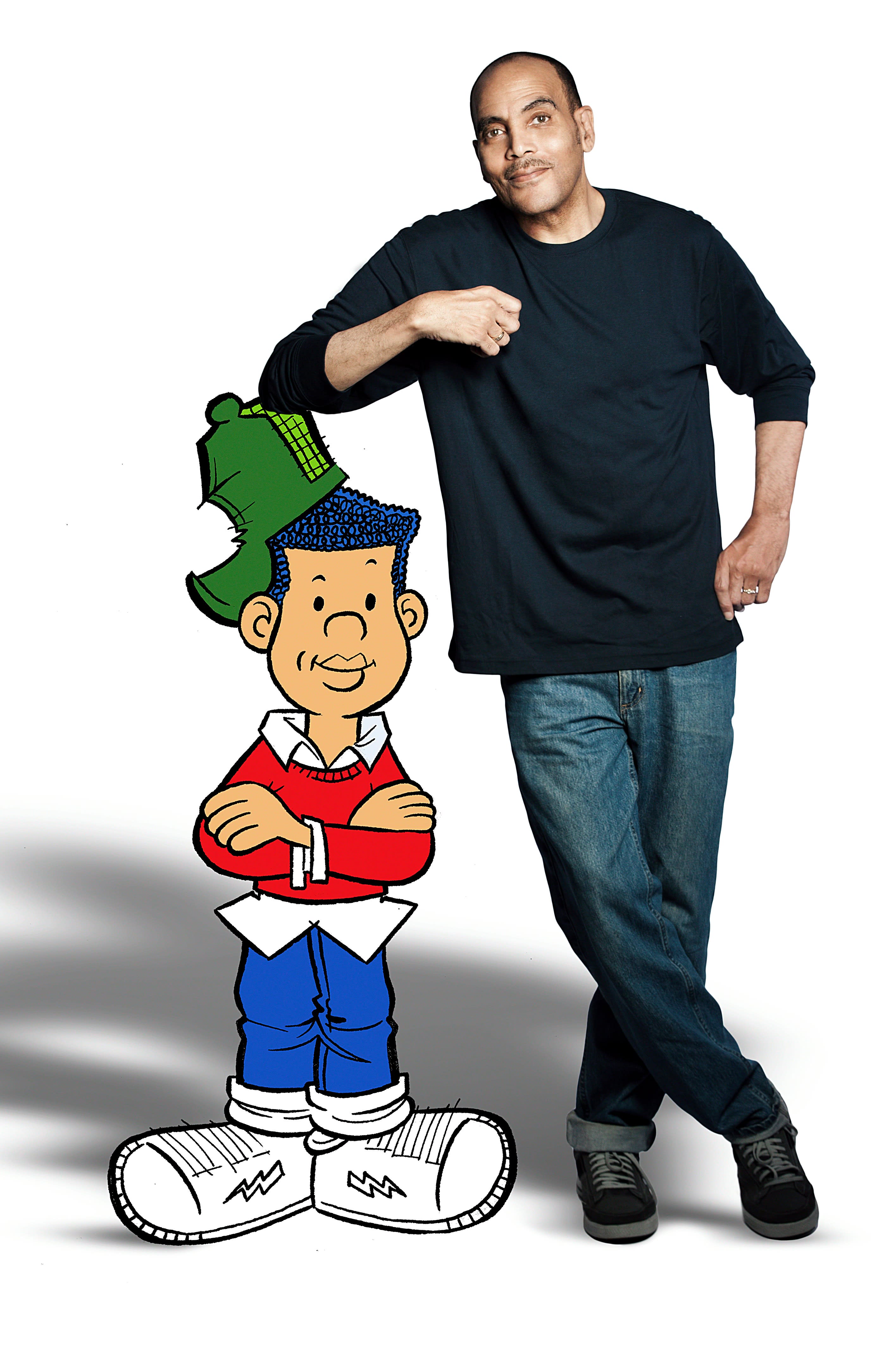

Cartoonist and SVA alumnus Ray Billingsley with the title character of Curtis, his syndicated daily comic strip.

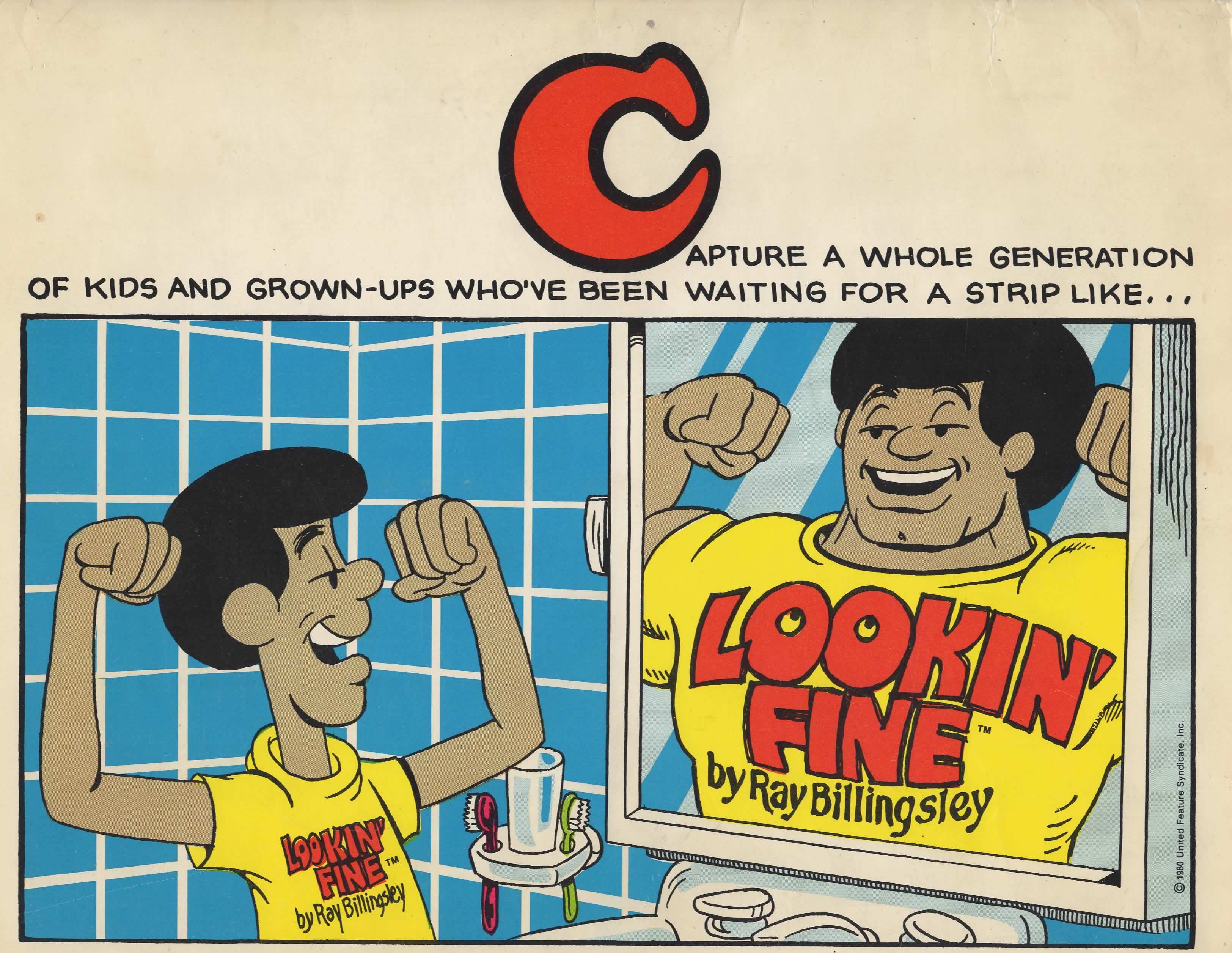

Raised in Harlem, Ray Billingsley (BFA 1979 Cartooning) was still a kid himself when he started drawing for the magazine Kids at the age of 12. He attended SVA on a full four-year scholarship and, following an internship at Walt Disney Studios, began drawing the short-lived strip Lookin’ Fine, a shrewd and funny comic centering on young African American adults.

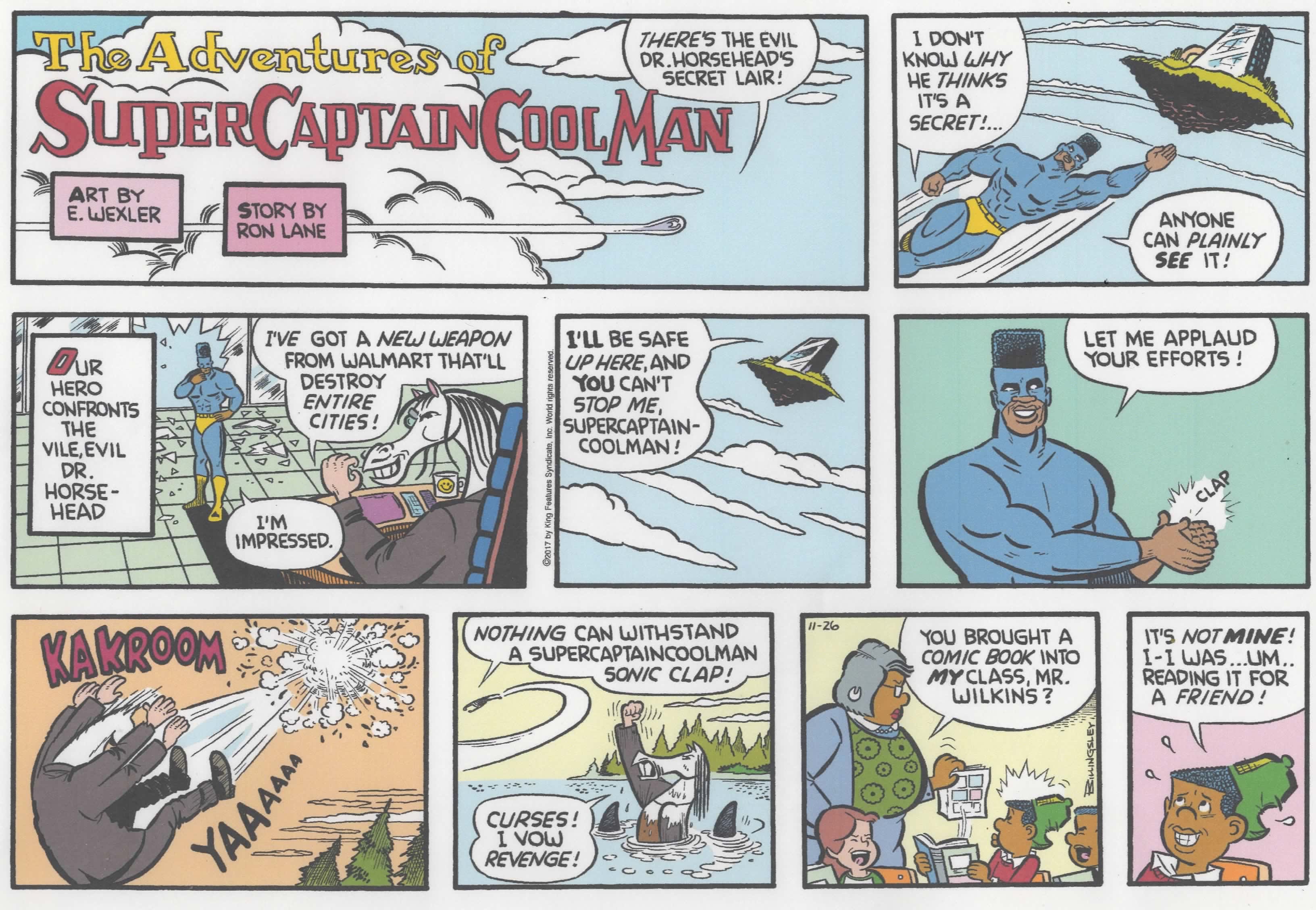

He debuted Curtis in 1988. Distributed by King Features, Curtis—a multilayered tale of an urban African American family of four and their wider community—has been a remarkable success, appearing in more than 250 newspapers in an age when print journalism is increasingly threatened, with an estimated daily readership of 43 million. In it, Billingsley blends charming domestic humor with sometimes startling commentary on topics such as racism, guns in schools and tobacco use. Curtis’ efforts to get his father to stop smoking earned Billingsley recognition from the American Lung Association; last year, Billingsley also became one of the first cartoonists to create a storyline addressing the COVID-19 pandemic when Curtis learned that his teacher was in the hospital with the illness.

These days, Billingsley is living and working out of his home in Stamford, Connecticut. We caught up with him several months ago to discuss his career, his time at SVA, and underrepresentation in comics.

Last summer, you went into New York City to join Black Lives Matter protests in the streets. Did you also find yourself thinking about what you might do in Curtis to respond to this moment?

It’s actually always on my mind. Things like this, they affect me personally. So it always translates down into my work.

When you started with Curtis, was it your intention to have a strip that would allow you to comment on topical events?

When I was first thinking of Curtis back in the 1980s, it wasn’t that sort of platform. But I sort of started drifting into those sort of stories, and the audience accepted. I knew just doing gags wouldn’t be enough for me. I cannot do a Beetle Bailey, where Beetle gets smashed by Sarge and is back the next day. I can’t have talking cats and dogs and ducks and things like that.

Instead, you have a strip with Curtis’ teacher, Mrs. Nelson, coming down with COVID-19. It was heartbreaking. That storyline really revealed her relationship with Curtis.

It is personal to me because she’s a real person. Mrs. Nelson was actually my third-grade teacher. One time she called my mother, and I thought I was in big trouble for something, and she just wanted to tell her about this artistic talent that she saw budding, and she encouraged my mother to push me along.

So in the Mrs. Nelson–Curtis relationship, you’re Curtis?

In many ways I was just like Curtis. If something bad happened, everyone in the room would just turn and look at me, because they’d know I did it. I think that actually helped me get through the early days of freelancing. I was a bold young person who didn’t really see boundaries, and that includes all the way up to the School of Visual Arts.

Did you have any “Mrs. Nelsons” at SVA?

There was Howard Beckerman, Harvey Kurtzman and of course my number one instructor was Will Eisner. And Will Eisner pushed me hard. He knew that I had been published, and when I showed him samples of work, he basically shrugged his shoulders and said, “So what else is there to you?” Then he started teaching me the value of learning different styles and being able to really carry a storyline.

Now, Will Eisner always came late. Students were always there before him. So we’d be sitting around, and we’re talking and chatting, and all of a sudden he’d enter the room and there’d be a great hush. If somebody stepped on a marshmallow, you’d have heard it.

Will was so strict on us that by the time half of the semester was over, half of the students had transferred out. They just couldn’t take it. Just imagine, you work all night on a project, and the teacher goes, “Eh. Do better.” A lot of people, their egos were a little too big, so they couldn’t take it. But I found it helpful. All experimentation I credit to Will Eisner. He challenged me to step up my game, stretch beyond what he saw as limitations.

What did you learn from Kurtzman?

Harvey Kurtzman, he was just crazy. He was eternally making jokes and doing these really funny drawings and he just encouraged humor all the time. His class was really a joy to go to. From the time he came in, he was smiling and laughing.

The journalist Richard Prince once wrote that one reason why Black comic strips are usually about children is that strips with Black adults are seen to be threatening.

I found that out the hard way, when I was drawing Lookin’ Fine. I had a chat with Morrie Turner of Wee Pals—he warned me right away, he said, “You’re going to be in trouble.” I spoke about drug use and inequalities in schools and stuff like that. And when you have adults talking about it on a comics page, if you’re next to Ziggy or Nancy or Marmaduke, it’s discomforting. But if a child says the same thing, he can get away with it.

All of us were basically learning on our own. We had to learn what worked and what didn’t, and take chances. Morrie Turner doing the first integrated strip, he took a lot of chances. But you can’t please everyone, so you don’t even try. I’m at the point where I’m basically drawing the strip for me, first. This is my world, if you want to come into it, fine. If you don’t, that’s fine, too.

In one story line in Curtis, we meet an older Black cartoonist named Quincy Shearer, who tells Curtis about the old days. He’s clearly modeled after Ted Shearer, who created the comic strip Quincy. Did you ever meet Shearer?

I never met Ted Shearer and that was unfortunate. I loved the guy’s artwork, his framing, and he was just a master of line. He had a strip where the composition, the panel construction, just drew your eye to it.

Usually when a Black artist met another one, we were immediate friends because on some level we know what the other one went through. When I first met Morrie Turner, we went and hugged each other, and he started crying. I said, “What’s the matter?” and he just said, “Congratulations.” And then we just sat and talked.

Another older cartoonist was Samuel Joyner. He told me a lot of the stories about cartooning during the time of blackface cartoons. Joyner told me he had to have a white friend bring his work to the editor to try to sell it. There were a lot of startling revelations to this man's experiences.

What was the main lesson that Joyner taught you?

Creativity at any cost. It’s not the money. It’s the need to express yourself and hope that people will like it. He did not seem to be bitter about anything.

Do you ever hear from readers who are unhappy about something in Curtis?

Sometimes it’s the smallest thing you can think of. If I mention a lot of rap music, somebody will complain. I had Curtis eating Rapper Puffs, a cereal, and some people didn’t like that. If someone gets upset at a box called Rapper Puffs, there’s a low threshold out there.

Did you feel a pressure, from yourself or others, to represent a certain kind of Black life in Curtis?

Yes, there is definitely a pressure but moreover a pressure to maintain a good standard. I have to have more hits than misses.

One of the things that was important was a strong Black family unit. In my strip, Curtis is the only one who enjoys a two-parent house. One of the characters lives with his grandmother; he doesn’t even know where his parents are. A couple times I’ve even had Curtis’ father say, “Curtis, this isn’t one of those strips where the kid outthinks the parent.”

How did you decide Curtis’ personality, what kind of kid he would be?

Charles Schulz was a friend. He was like a father figure to me. I was sort of messing with him at one point, I said, “Lucy is the loudmouth, Schroeder plays the piano, what does Franklin do? He doesn’t even get angry at anyone. He’s just a good guy.” And Schulz didn’t really have an answer. I knew what Schulz was trying to do. We had the marches, we had the assassination of Malcolm X, and he decided to bring along a very nice character.

But that’s what I tried to get away from. Curtis can be mischievous. It even goes to the way he’s dressed. Curtis made his debut in ’88, and in ’88 you were considered to be a little troublesome if you wore your hat backwards, if you let your shirt come out under your sweater. Curtis did all that way back then when it meant something. And unlike other characters, he had no problems when talking to girls.

What are the challenges for Black cartoonists starting out today?

A lot about the industry isn’t really that inspiring. I don’t have a book deal. I have one company that actually told me that Blacks really don’t read, and they insinuated that whites wouldn’t buy it. So we’re still at that. No merchandise nor animation deals—nothing. Despite my decades-old success I still feel overlooked, like I have to continually prove myself. it really bothers me.

One thing I hear from Black cartoonists is they are trying to sell something and the paper will say, “We already have Curtis.” It’s not fair. I’m not the voice. Every voice is different and every voice is welcome. When Baby Blues was coming out, nobody said we already have Hi and Lois. It doesn’t work that way. But it’s the hardest thing to break.

I’m really nobody’s role model. Robb Armstrong, he has a very good strip, his main character is a policeman, very different. Keith Knight has a strip out that’s very different. Barbara Brandon-Croft. had a syndicated strip, Where I’m Coming From, written from an African American point of view. There is also Darrin Bell, who won a Pulitzer for editorial cartoons. We need people like that. Throughout the web, we see a lot of Black voices, women and men, they can’t sell it. But with the Internet they can at least express it. They can have their individual stories told, their own voices and creative experiences.

What do you see as the future for Curtis?

As long as there is some sort of craziness going on in society, I can bring that into the strip. Which is why the strip has survived for so long.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Michael Tisserand is the author of Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White (HarperCollins).

A version of this article appears in the fall/winter 2020 edition of the Visual Arts Journal.