Read about the artist and SVA alumnus who creates “the way nature does” in this article from the fall/winter 2024–25 “Visual Arts Journal.”

In his heart of hearts, artist Willie Cole (BFA 1976 Media Arts)—whose illustrious career spans decades—says that he is a painter. But it is his sculptural work and printmaking, which often employ unexpected, usually upcycled objects, repetition, and a spirit of play, that have largely fueled his public acclaim, and led to a number of recent high-profile collaborations with avant-garde fashion house Comme des Garçons, Italian luxury brand Tod’s and Yamaha.

Cole’s process, rooted in a serendipitous yet associative relationship to the materials he uses, is open and receptive to change. “I don’t really look for objects, the objects come to me,” he says. “I let the materials do their own thing. If I do have a concept, I don’t know immediately what medium it will be in. I just play and accept the results that come from that.”

“I don’t feel like I’m part of any kind of -ism,” he says. “I believe that I can access creative energy from the universe. And I proceed that way every day.”

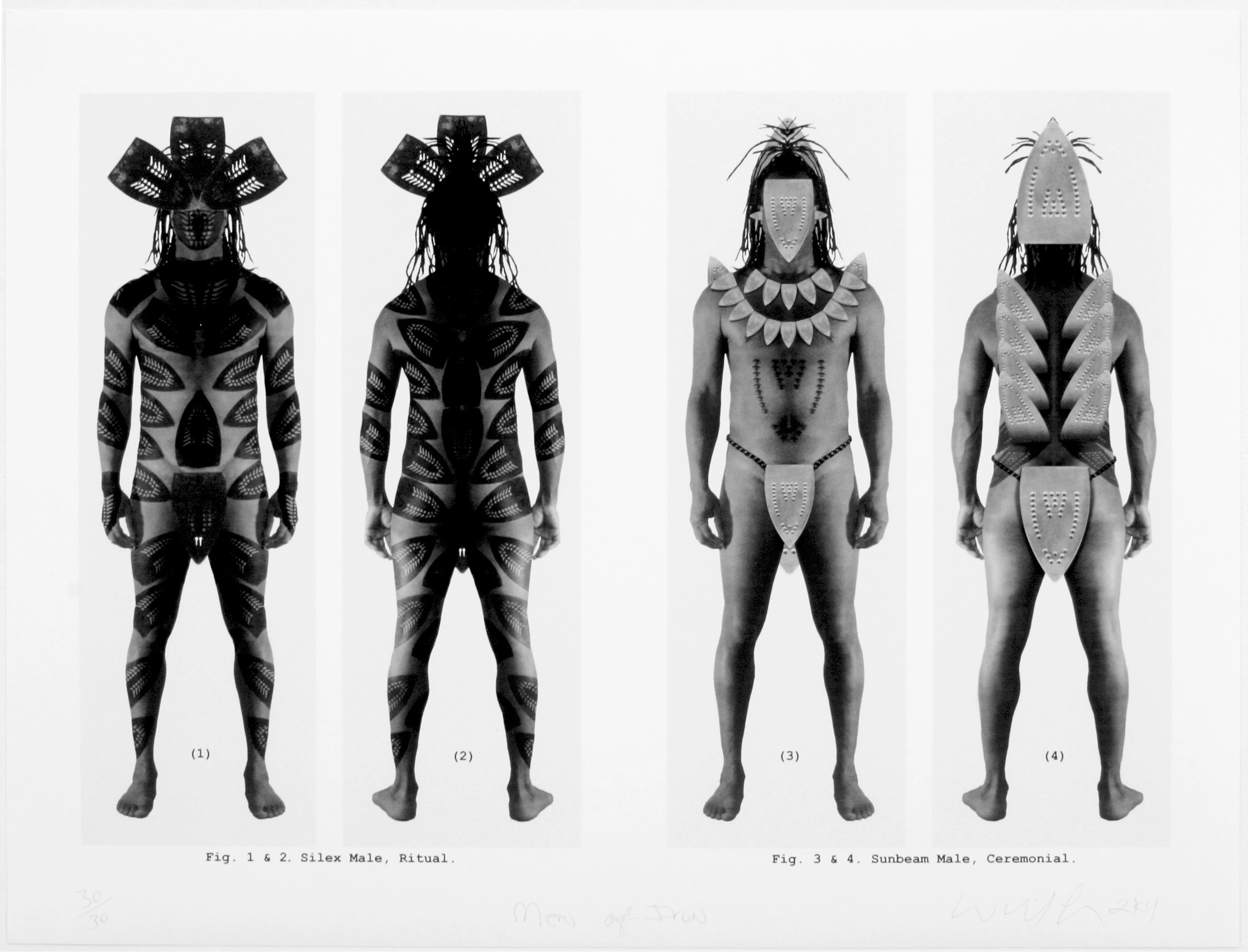

Cole often works with “single objects multiplied”—shoes, plastic bottles, steam irons, musical instruments, and more—reimagining and reconfiguring their potential to create new visions and fields of interpretation. “I see each object as a building block or cell,” he says. “I create the same way nature does: by multiplying single cells against themselves until they become something new.”

Cole’s material acts of arrangement and composition are often prefigured by a spontaneous unfurling of psychological referencing. “People process all they see through their own individual filters,” he says, and while he is aware of the many filters he has accumulated throughout his life, he is not tied to any one perspective: his coming of age in an era of Black consciousness in the ’60s, an interest in Buddhism in his 20s, artists like Carl Andre, Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Arman, Katsushika Hokusai and Pointallist and Impressionist painters; or the many women in his family. (“I grew up with all women,” he says. “My grandmother and my great-grandmother, aunts and sisters and female cousins.”)

Early in his career, as he was expanding into sculpture, he landed the now-coveted Studio Museum in Harlem artist-in-residency program. He was selected based on his paintings and woven-steel sculptures, made from 10-foot-by-1-inch strips of scrap metal from a business next to his apartment in New Jersey. The opportunity proved to be pivotal.

“I lived in New Jersey and caught the train to Harlem everyday,” Cole says. “On the way to the train station, I saw an iron in the street that had been run over by cars and trucks. I lived near the highway. It was completely flat. At that time, my best friend was a dealer of African art. So when I saw this iron in the street, I immediately saw it as looking very African. I saw it through my filters. So I brought it back to my studio in New Jersey and I began to photograph it. After a while, it just began to say so many things. It became a part of my life.”

The iron would come to define the next stage of his practice—his “scorch work.” Cole began to make a list of what the iron meant to him symbolically, spiritually, physically, and functionally.

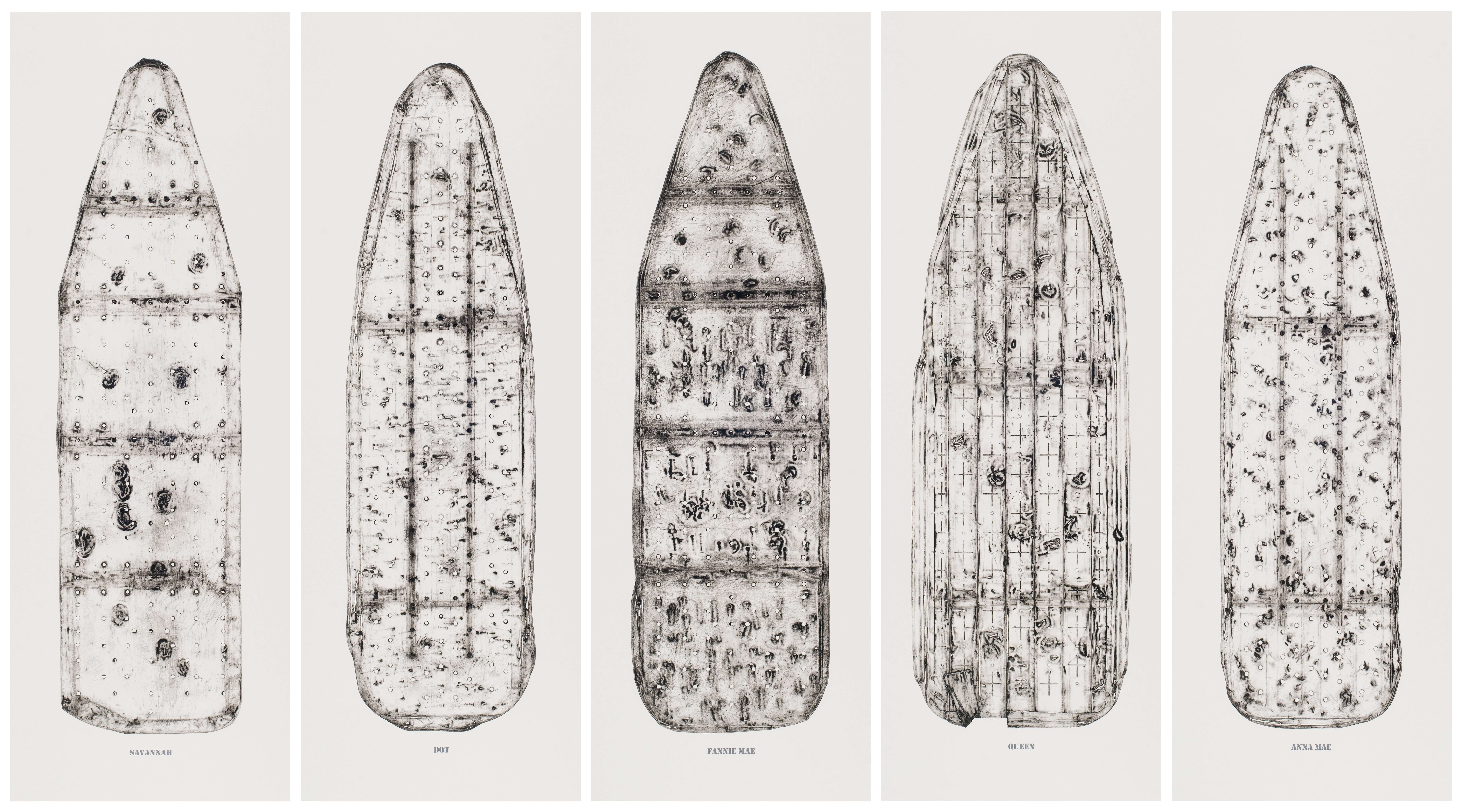

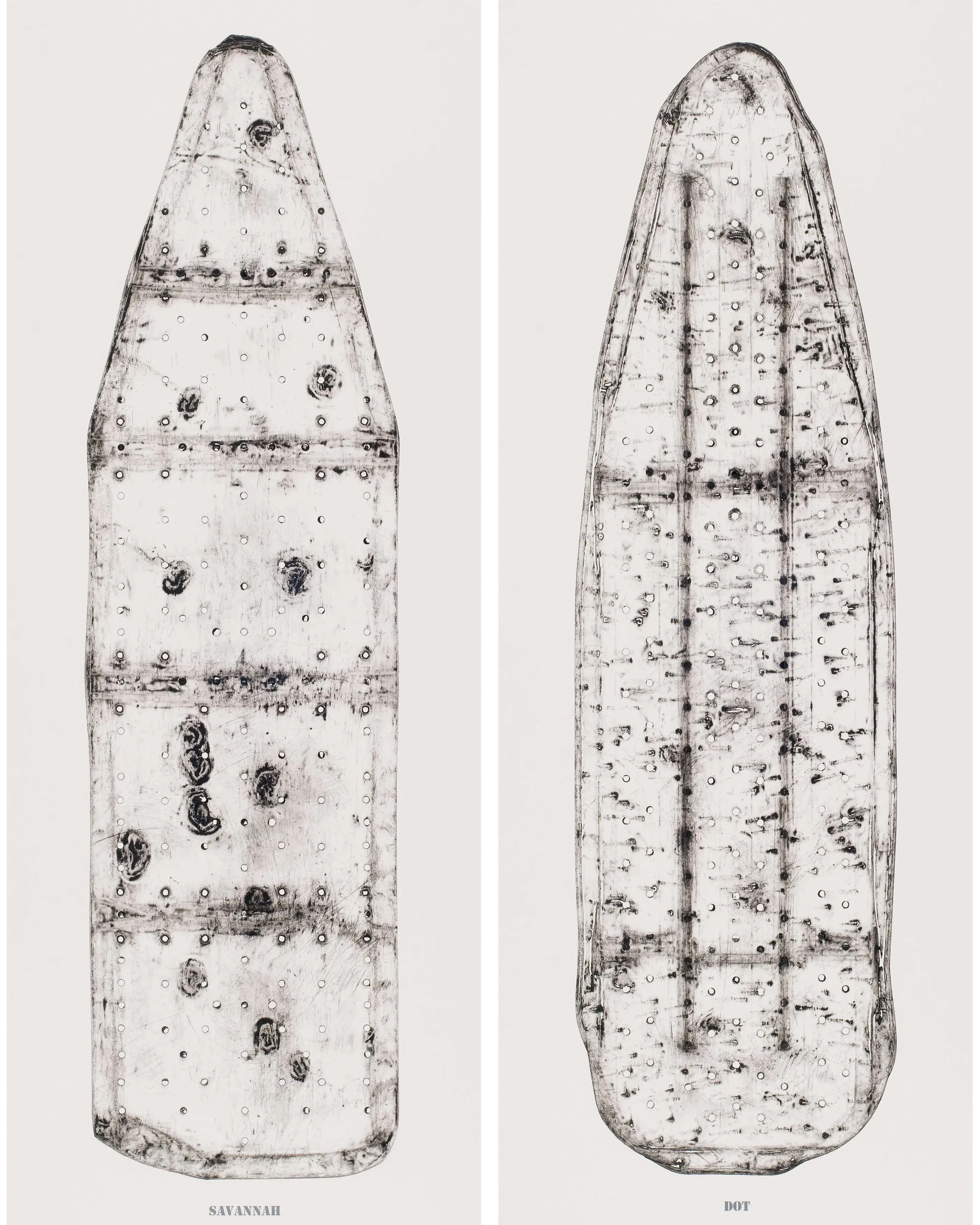

“That list became a catalyst for work for probably the next 10 years,” he says. Stories and associations related to the formal qualities and social meanings of irons and scorching—the making of marks with either burning or red-hot instruments—revealed themselves over time: Zulu shields, heat, previously unnoticed burn marks on Cole’s studio floor, his own family history in relation to antebellum domestic work and more. Scorch works made by applying household steam irons to wood, paper, and plywood, as well as stunning wood-block and intaglio relief prints of distressed ironing boards, are all highly regarded works from Cole’s oeuvre, and still part of his practice today.

Cole had another unexpected encounter with an object when, while searching a thrift store for sneakers for a sculpture, he was unexpectedly blindsided by a pair of high heels. The discovery initiated an ongoing series of sculptures made from heels, some made with actual shoes and others cast in bronze.

“Women’s shoes are much more interesting and intricate than men’s shoes,” says Cole. “Some of them are like architecture.” They also have personal significance. “Most, if not all, of the women in my childhood wore and loved high heels,” he says, and his nearly 90-year-old mother keeps a collection of miniature high heels in a cabinet at her home. His shoe sculptures can be read as either abstract or figurative and have also been featured in his collaborations with Comme des Garçons and Tod’s.

For the Comme des Garçons Homme Plus Autumn/Winter 2021 collection, Cole created headpieces made of black high heels. The creative process between Cole and founder Rei Kawakubo’s team unfolded digitally during the pandemic, with Cole sharing photographs of himself wearing the headpieces that he later turned into watercolors that are works of art in their own right. Kawakubo’s vision for the headpieces, as well as some textile prints, were riffs on Cole’s shoe masks and assemblages—one of which, Shine, is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and on view at the museum’s ongoing exhibition “Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room.”

Another body of work spawned from a singular object are Cole’s sculptures of cascading chandeliers made with thousands of plastic water bottles, with the largest to date measuring 12 feet by 8 feet. He started collecting the bottles when he was invited to create work for an outdoor sculpture park that did not have a budget for materials or fabrication. While his plastic-bottle sculptures are now often framed within conversations on the environment and climate, Cole’s initial relationship to the material was more practical—the empty bottles are free, durable, and abundant.

“I wasn't thinking about the environment in an overt way because I have lived with that awareness my whole life,” Cole says. “I was not a little kid who littered or any of that kind of stuff. So I didn't think of myself as doing anything extraordinary to save the environment.”

Nevertheless, the work has resulted in several projects with students at schools and universities, including a 2023 rendition of a lounging figure made from 20,000 plastic bottles at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center in Texas, and commissions for spaces all over the world, from the median of Park Avenue near 72nd Street in New York City and private homes in Pennsylvania and Brooklyn to a makeup store in Australia and a monastery in Colombia.

Artist Willie Cole (BFA 1976 Media Arts) with one of his saxophone “birds,” which pay homage to Charlie “Bird” Parker and Kansas City’s rich jazz heritage.

Artist Willie Cole (BFA 1976 Media Arts) with one of his saxophone “birds,” which pay homage to Charlie “Bird” Parker and Kansas City’s rich jazz heritage.

Cole has also worked extensively with musical instruments. For a 2022 public art commission, Ornithology, at Kansas City International Airport, Cole’s signature filtering of thought associations landed on a prototype: saxophones recontextualized in the form of a bird.

“It was a no-brainer for me,” he says. Airplanes mimic birds in flight; “Bird” was the nickname of jazz-saxophonist legend and Kansas City native Charlie Parker; and the city is known for the adage, “Jazz was born in New Orleans, but it grew up in Kansas City.”

The project took two years to complete. “I ordered 300 saxophones,” says Cole. “My first prototype involved 30 horns per bird. I wanted to make 10 birds. That was the first month. By the third month I had a whole new concept for the design.” Ultimately, Cole used fewer saxophones per sculpture and created a dozen birds hanging from the ceiling and one at ground level for visitors to see up close. Inspired by the Jazz District, the location of the Kansas City studio he used for the project, Cole decided to hold onto the studio and continue working with the leftover saxes, even though the airport project is completed.

For another project, a collaboration with Yamaha, Cole reconfigured 75 recycled guitars into sculptural works for “No Strings,” his 2022 solo show at Alexander and Bonin in New York. Well received, it led to another solo show of musical-instrument sculptures, “Lyrical Reconstructions,” held earlier this year at Haley Gallery in the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, in Nashville.

This recent, music-related work has kept Cole’s interest. When asked about what’s next, he says, “What’s next, in terms of an object? I don't look for objects. I wait for them to find me. But every object I’ve worked with, I’m never really finished with it.”

Willie Cole’s work is in the collections of the Met and Museum of Modern Art, both in New York, and has been on view in countless solo and group exhibitions at museums, galleries, and academic institutions such as the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. He has received numerous public and private commissions for his work, including a recent outdoor installation on New York’s Upper East Side mounted for the Fund for Park Avenue and the New York City Parks Department of Parks and Recreation. For more information, visit williecole.com.

Diana McClure is a writer and photographer based in New York City. Her essays, reviews and profiles have appeared in Art Basel magazine, Art21, Cultured, catalogs, monographs, and other publications.

A version of this article appears in the Fall/Winter 2024-25 Visual Arts Journal.