Derrick Melander,

Trace

(detail), 2016, folded secondhand clothing, steel and wood frame.

As recycling and reuse become central to a modern way of life, equally propelled by the greenest of intentions and trendy capitalist schemes, artists have always found compelling ways to engage materials beyond their original contexts. From Marcel Duchamp’s infamous Fountain, which proposed a urinal as sculpture, to Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui's bottle-top installations to Louise Nevelson's recycled assemblage sculptures, the reuse or adaptation of objects has been central to modern and contemporary art practices.

Hanna Washburn (MFA 2018 Fine Arts), Derick Melander (BFA 1994 Fine Arts) and Joseph Fucigna (MFA 1988 Fine Arts) are three artists who work in this vein, albeit from three different points of view. Washburn's practice stems from a deeply personal engagement with her own old clothing, stored for a decade or so in her parents' basement in Wellesley, Massachusetts, before she incorporated them into her work. Melander's work also involves old clothing—items that he collects or receives from donation centers, which adds a deeply communal aspect to his practice. And Fucigna, who has worked with plastic fencing, rubber-tire inner tubes and most recently silicone (in the form of hand-therapy putty or Silly Putty), develops an almost-metaphysical relationship with his materials. Through a playful and intuitive exploration, he uncovers their alternative identities, molding them into abstract forms beyond their original intent.

Hanna Washburn,

Imagining the Future

, 2018.

All three artists allow their relationship with their materials to unfold, taking an investigative approach to the creation of pieces that work within the limitations of what is on hand. Each artist uses volume, mass, shape and color as guiding principles. Both Melander and Fucigna are further along in their careers and have surveyed how their work can most effectively connect with audiences. For Melander, the emotional engagement of his audiences runs parallel to the monumentality of his folded and stacked textile-based installations. For Fucigna, his use of accessible and familiar materials encourages viewers to enter into his organic sculptural work. In the case of Washburn, abstract sculptural forms sewn and stuffed with Poly-Fil seem to represent a sort of alchemization of her adolescence.

"I used to wear a lot of floral patterns," says Washburn, who next month begins a residency at the

. "So I started to get really interested in why that was. I'm from suburban New England and I grew up with my mother and my grandmother wearing a lot of patterns ... kind of like Laura Ashley–style floral patterns. I was interested in the type of femininity in it, the taste level that it constructs. It was so personal to my upbringing ... an aesthetic that I had kind of inherited."

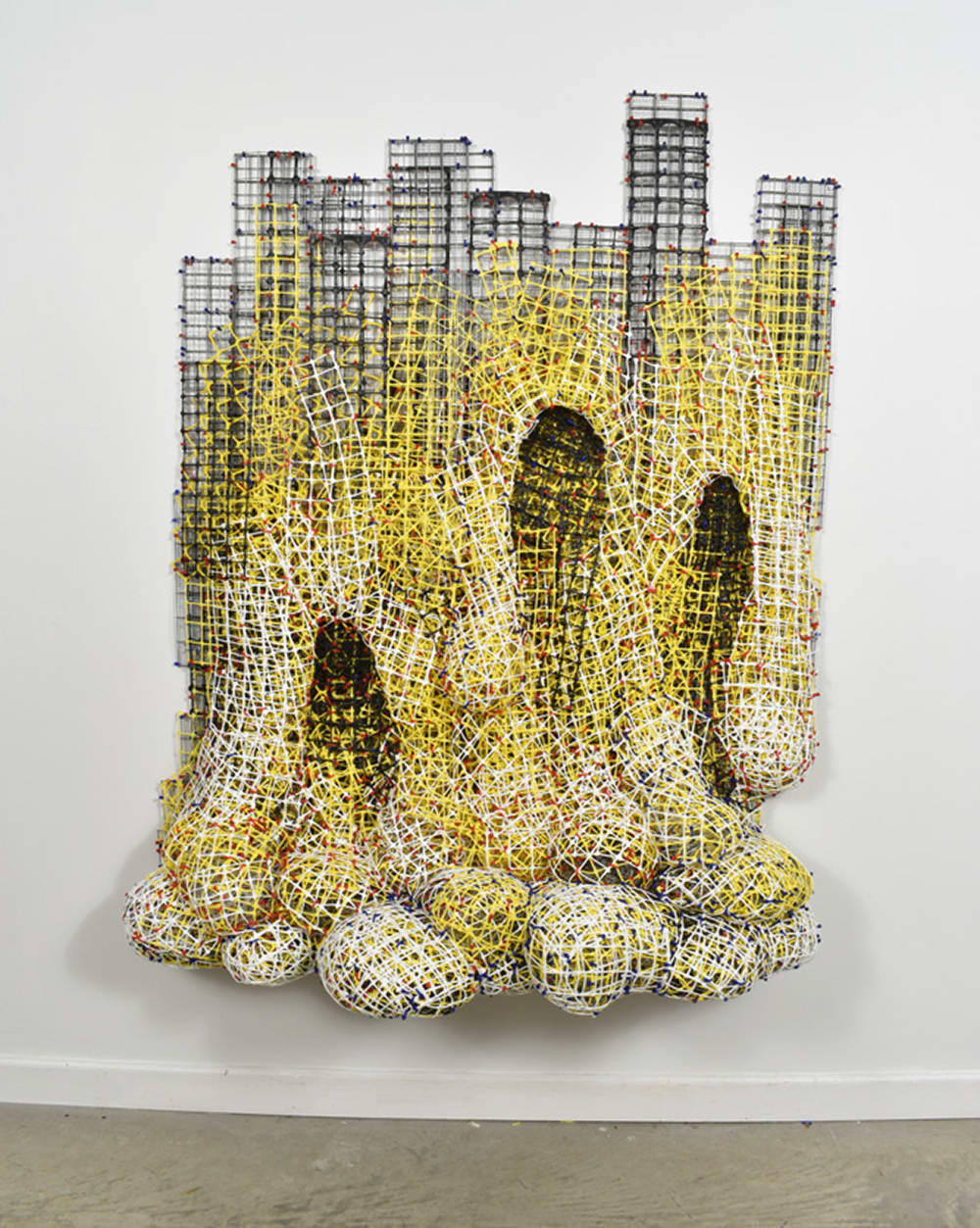

Joseph Fucigna,

Brainstorm

, 2014, plastic fencing, cable ties, lead fishing weights.

The social content of her work, although not obvious on the exterior, is represented by soft, organic, bulbous forms—a nod to the shapeliness and expansiveness of the female body. Of all her teen years, Washburn homed in on the age of 16, which she characterizes as "a time when you're starting to really develop what you're interested in and you're really kind of passionate." Several of her work's titles reference the literature and music of that time. Washburn's love of texture, color and abundance was unearthed, validated and filled with meaning in graduate school, coalescing in an understated critique of her particular sociocultural upbringing, and her repurposing of intimate material seems to be a first step into fruitful territory that engages both form and content.

Having used found materials throughout his career, Fucigna has allowed their shapes and qualities to take the lead in the ever-evolving relationship between himself as the artist and his materials as his subject. For decades he has worked with nondescript industrial supplies originally destined for purposes other than art making—material choices that cannot be easily inserted into new narratives. In a sense, Fucigna disrupts the assumed identity of these objects and situates them in a nonlinear space of visual communication.

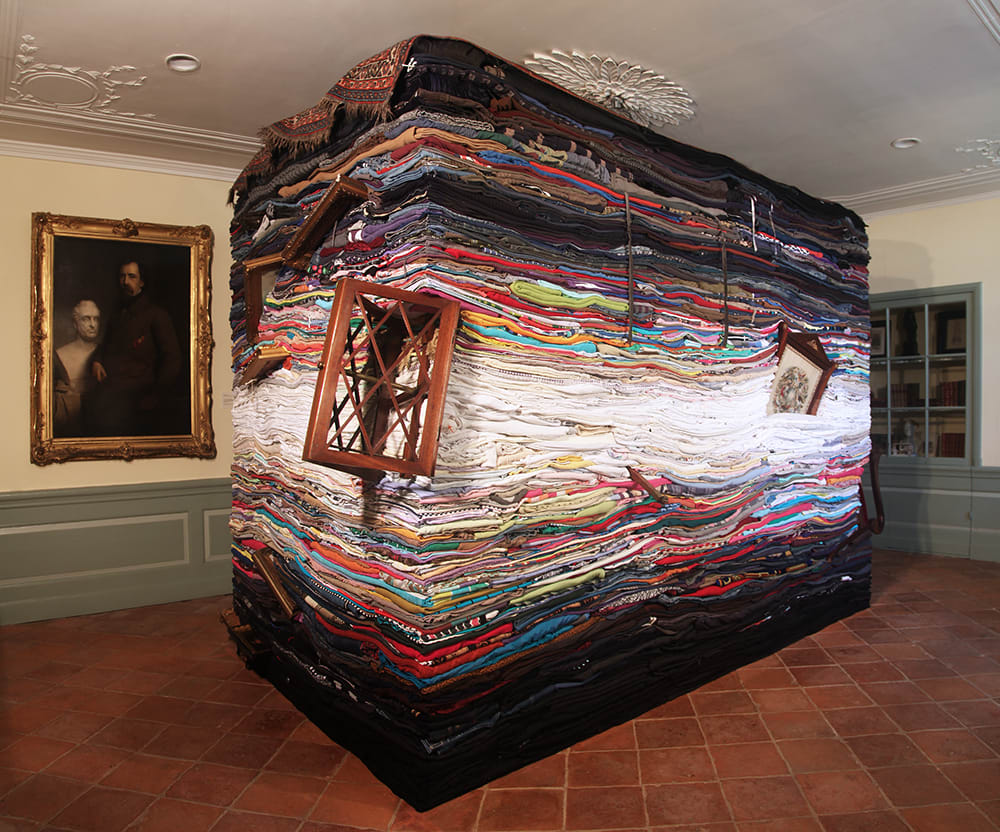

Derrick Melander,

Tollens

(back view), 2015, secondhand clothing, antiques, wooden armature.

As an undergraduate, Fucigna attended Alfred University, a small university in Western New York known for its strong ceramics program. The attention to detail, mastery of a medium and its subsequent manipulation into something magical—all central to the world of craft artists such as ceramicists—made a lasting impression on him. With this foundation, his time at SVA allowed him to break out into less tradition-bound modes of expression, including striking sculptures made of rubber and wood.

For the last 15 years or so, he has worked with plastic fencing in an intuitive process that involves finding something in the material that resonates with him and then figuring out what it "wants" to do. In the early phase, his relationship with a material is formal, as he discovers its unique physical properties and possibilities; later, once it has become more familiar, narrative hints begin to take shape. Qualities such as the manufactured color and line of the fencing are considered and transformed into organic, mound-like forms reminiscent of those found in nature.

"I'm not one to do the heavy machinery and fabrication," Fucigna says. "I want to work in a simplistic, inexpensive type of way. I also consider myself to be old-school in terms of the idea of the process and the building and what I learn through the development of a piece and the direction of it. … That hands-on element, being involved and being in the studio—I love being in the studio. I'm not sitting in front of my computer constructing things and then sending them off. … Finding the materials, looking at the materials, working with the materials, becoming familiar with the materials [all] become a very one-on-one experience."

Hanna Washburn,

I'll Believe in Anything

, 2018.

As chair of the studio arts program at Norwalk Community College in Connecticut, Fucigna is well attuned to the need to be direct. He has cultivated an ability to speak on multiple levels to a variety of audiences. This skill translates into artwork that combines a use of simple and accessible materials with an execution of sophisticated and at times sublime sculptural work.

Working on a much larger scale, a recent work of Melander's required two tons of used clothing. Brought in by forklift and created by a 14-person production team, the monumental installation was commissioned by the fashion brand Diesel for the 2017 Young International Art Fair in Paris. The clothing, which was folded using a special technique developed by Melander through trial and error over many years, was meticulously sorted by color and stacked into a cube-shaped armature. He has executed similar projects for Eileen Fisher and The Chapman Perelman Foundation's Change Fashion initiative; in February, he will create a public sculpture in Hong Kong, commissioned by luxury real-estate developer Swire Properties.

Melander's work was not always so grand. Early in his career, feeling stunted by the theoretical overkill of graduate school, Melander began reading and experimenting with the work of psychoanalyst Carl Jung and his theories on lucid dreaming. He decided to set an intention every night to create a piece of art in his dreams. The experiment eventually led to a body of work involving suitcases that then led to an idea to stack the suitcases on piles of used clothing. For the first two years of this exploration, Mary Help of Christians Church in New York City's East Village passed on unusable donations to the artist.

Joseph Fucigna,

Big Drip

, 2013, plastic and metal fencing, cable ties.

Working with the bags of clothing struck a chord with Melander, who saw in the discarded garments the emotional imprint left behind by the donors. Clothing as a record of physical presence became a direct and concrete metaphor for a family. He began folding and stacking the clothing according to formal principles such as color, pattern or texture, transforming them into something he now calls "a collective portrait." Initially the work, which at times required nine months to complete a single piece, fit into a solo studio practice. Eventually it took on a life of its own. Melander realized that the larger a piece was, the more emotional resonance it had with audiences. Due to logistics, however, Melander was only able to show his work in New York. He began to ask himself, How do I do this in other places?

The answer turned out to be at colleges and universities, where student support for production was abundant. Conceptually, Melander understands that clothing can function as a boundary, as a performance or as a representative of a particular population. However, as his practice has grown it has turned out to be a form of personal connection. As the works get bigger and more complicated, colors and patterns become more and more precise, and more help is required, leading to community building among the teams of people producing the work. In regard to this unexpected consequence, he says: "When you're folding clothing it does foster a really easy conversation. ... Sometimes you talk about your love affair, movies, a book. Sometimes you talk about art. It ends up becoming this real kind of sharing and community experience. That's an added bonus to doing this collaborative work."

Another form of connection takes place once an installation is complete. Viewers are often compelled to touch the work, inspired by a sense of awe and wonder. Ultimately, Melander makes this connection with his audience by using form, volume, mass and color to generate emotion.

"Really what I am hoping is that people will come together and feel or even understand that we're all part of the same family," he says. "That we're all connected."

Joseph Fucigna,

Yellow_Black_White Drip

, 2017, plastic and metal fencing, cable ties.

A version of this article appears in the fall 2018 issue of the Visual Arts Journal.