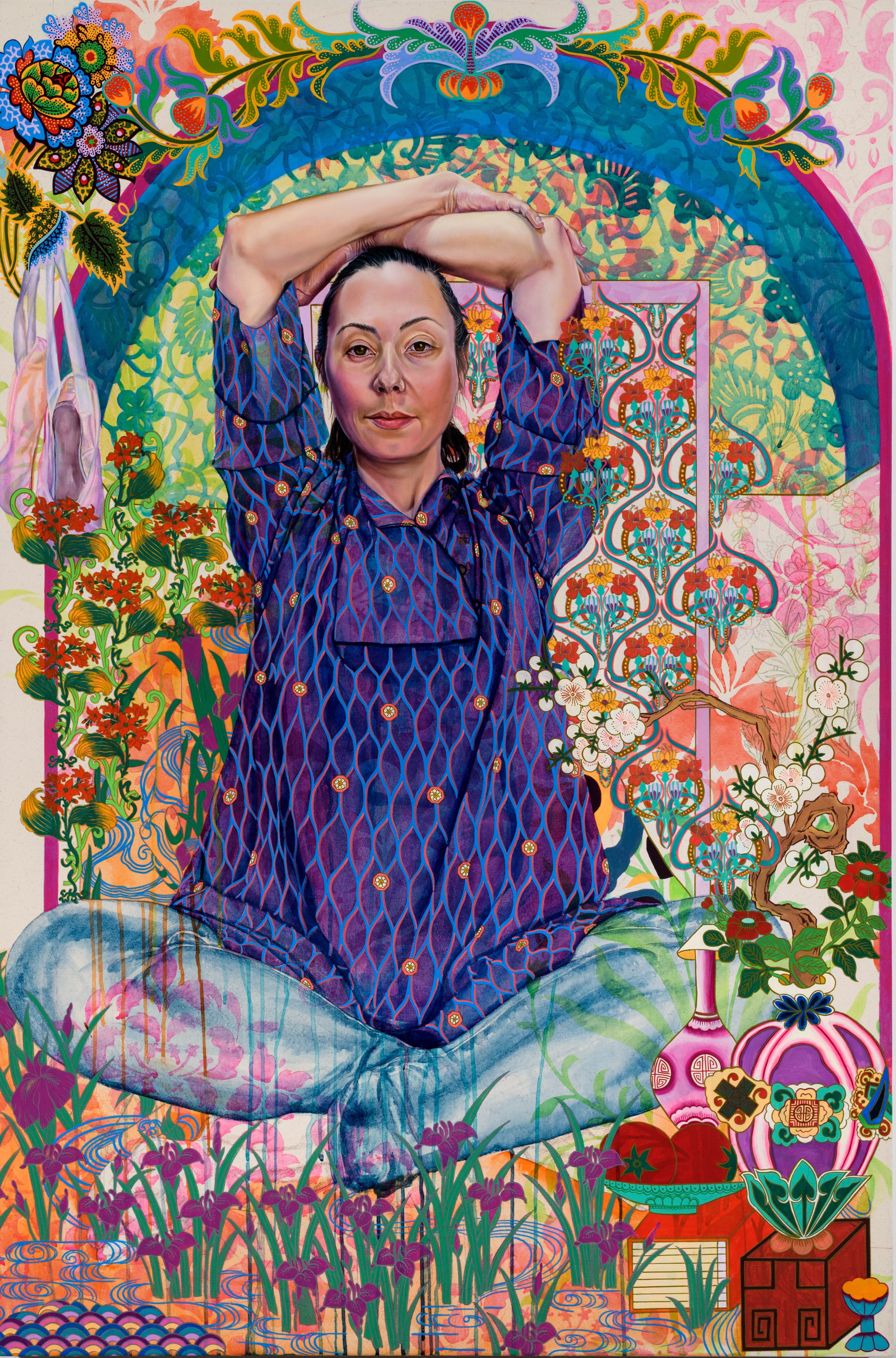

Kira Nam Greene, Ellen’s Niche with a Gaze, 2019, oil, gouache, colored pencil and acrylic ink on canvas.

Some of the most powerful art is born out of upheaval. For the paintings of “Women in Possession of Good Fortune,” an ongoing series by artist Kira Nam Greene (MFA 2004 Fine Arts), the catalyst was the 2017 Women’s March, which occurred the day after President Donald Trump’s inauguration and is, to date, the largest single-day protest in U.S. history.

“I was thinking about the collective action and the power of women getting together,” Greene says, “and about how I can represent that power and the positive aspects of women’s representation, visually. It occurred to me that I’m surrounded by so many beautiful, strong women who are doing so many great things.”

Greene set out to make portraits evoking historical views on traditional portraiture and feminist art, taking as her subjects successful and creative women who she personally or professionally knows, a circle that includes painters, photographers, a ballet dancer and an architect. “Portraiture always has a level of intimacy and idealization,” she says. “But things are much more complex when you are dealing with a really close friend.”

To begin each painting, Greene reviews historical figurative paintings with her subjects to find inspiration for possible poses. She also talks with them about their lives and upbringings, mining their backgrounds for objects and visual motifs she can use to signify their achievements, heritage and personhood—paintbrushes, Russian art deco motifs, a mother’s dress from her homeland of Trinidad and Tobago, even their cats.

“I’m interested in representing women, not as in marriage portraits, but with professional portraits similar to The Ambassadors, by Hans Holbein the Younger,” she says. In that famous 16th-century painting, two men confidently gaze at the viewer from a scene that is rich with textiles, patterns and symbolic objects, all of which attest to the subjects’ high intellectual, social and financial status. “I want to give [my models] agency in how they want to be seen.”

Rather than have her subjects pose for the paintings—an arduous, time-consuming process—Greene photographs them in her studio and then works off of a photograph in creating the final piece. The women often wear colorful, multipatterned clothes, in homage to the feminist Pattern and Decoration movement from the mid-1970s. Pattern and Decoration art prized aesthetic elements that were commonly found in craft and design, and its compositions often did not distinguish between background and foreground. Many of the patterns on the models’ clothes reflect their biographies—their parents’ ethnicities, for example, or where they grew up. Kyung’s Gift in Pojagi, the portrait of painter and mother Kyung Jeon Miranda, highlights the Korean fabric collage tradition called Bojagi (other details include the Chinese Zodiac symbol of the rabbit, for Miranda’s birth year; and a replica of Miranda’s own work).

Kira Nam Greene, Renee’s Room (with Three Chairs and a Painting), 2018, oil, Flashe, colored pencil and acrylic ink on canvas.

To move beyond just faithfully reproducing the photographs, Greene incorporates various painting and drawing methods and mediums in each work. Some are complementary, others are contradictory. “The biggest difference between the photography and the painting is the textural differences and the sensuality of the materials,” she says. “I like to see the maximum diversity in the materiality in the painting.”

She fluctuates between rich and supple paints, watery ink washes, exposed under-drawings and hard-edged graphite elements, all of which serve to highlight her thinking process and expose how the painting is made. Aside from portraying her subjects at life size or slightly larger, Greene makes most of her compositional choices as she works. Her realistically rendered figures are confronted with patterns and design details that bleed out and threaten to overtake them, creating a cacophony of color and pulsating rhythm.

“This defamiliarized space invites extended sensual encounters with the paintings, where diverse representational modes coexist, and where the body appears as if seen for the first time,” she says.

The title of Greene’s series plays on the opening line of one of her favorite novels, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” Greene’s reformulation rebukes the persistence of sexism, while celebrating her subjects’ collective accomplishments and experiences.

“Now men are no longer the only ones in possession of good fortune—and not just the financial aspect,” Greene says.

Greene’s work has been exhibited in numerous exhibitions domestically and internationally, and she is represented by the Lyons Wier Gallery, New York. She has work included in the permanent collections of the Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska; and the Progressive Insurance Art Collection, Mayfield Village, Ohio; among others. She was a semifinalist for the 2019 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition at the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC, and a finalist for the 2019 Bennett Prize. For more information, visit kiranamgreene.com.

Dan Halm (MFA 2001 Illustration as Visual Essay; BFA 1994 Illustration) is an artist, independent curator and project manager for SVA External Relations.

A version of this article appears in the fall/winter 2020 edition of the Visual Arts Journal.