SA/Stormtroopers hold the banners of their respective units with the swastika and slogan “Germany Awake.”

Can a symbol ever escape its most nefarious usages and connotations? And should it? Renowned art director and writer Steven Heller, co-chair of MFA Design at SVA, has spent much of his career wrestling with such questions—about where designs come from and the lasting influence of a brand. But one symbol, in particular, has been an object of long-term study. The Swastika and Symbols of Hate: Extremist Iconography Today, co-published by SVA and Allworth Press and released earlier this fall, is Heller's treatise on the swastika, the hooked cross adopted and ultimately weaponized by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis between 1920 and the end of World War II, as well as one of the oldest and most widely used symbols in human history.

First published in 2000 and then revised in 2008, the book was originally titled The Swastika: A Symbol Beyond Redemption? "It was just a way of purging my own interests and looking at it from its truly benign perspective and seeing how it evolved," Heller says. The first edition entertained the possibility that the swastika could be reformed, or perhaps more accurately returned to its associations with good fortune and spirituality that predate the Nazi usage and are, in fact, still its primary significations today in many parts of the world.

"Initially, I was sympathetic [to rehabilitation efforts]," he writes in the new edition's introduction, "however, as long the Nazi iteration continues to elicit destructive power, there is no way it will ever be redeemed." Writing about such a stance, he has noted that, "People for whom the swastika has spiritual import have a right to this symbol. Nonetheless, I would feel even more guilty if I did not take a stand against its use in our cultural context as anything other than an icon of evil."

Disturbingly relevant circumstances outside his own study and reflection motivated the new polemic. "This version was really prompted by Charlottesville," he says, referring to the August 2017 Unite the Right rally in Virginia that killed a counter-protester and led President Donald Trump to famously equivocate about the "very fine people" on both sides. "What could I do to make some sort of statement about the Trumpian period?" Accordingly, the revised edition includes additional material on old and new hate logos, as it examines graphic design's role in far-right extremist ideology today.

A anti-hate design intervention in a New York City subway car.

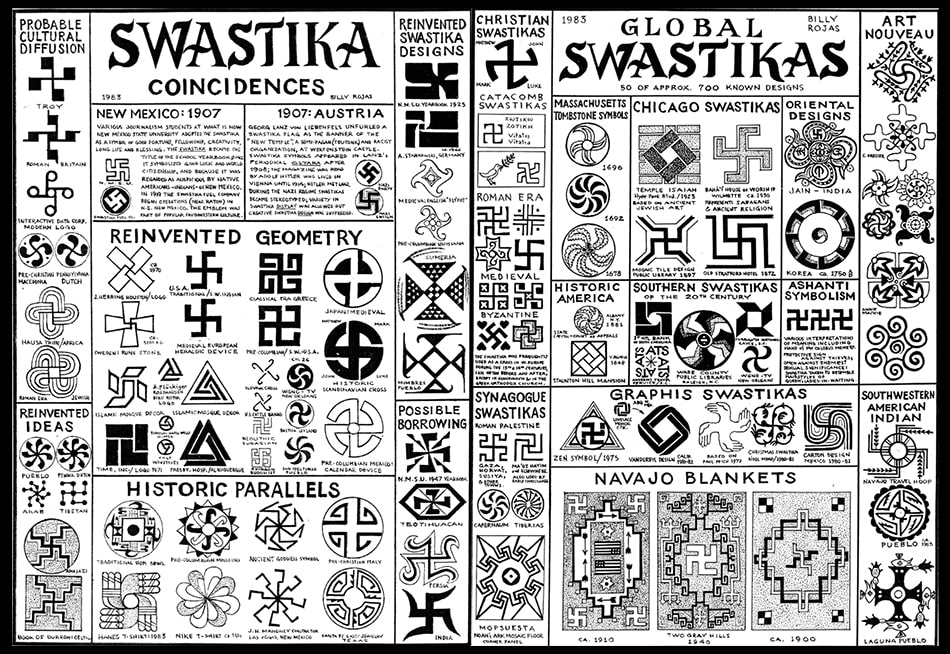

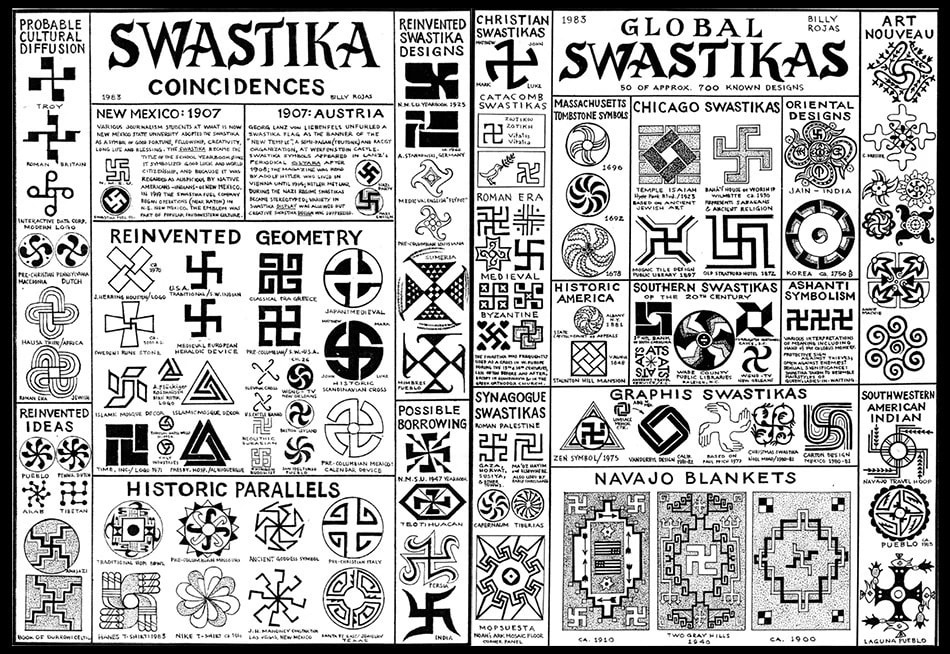

"Few symbols have had as much impact on humankind as the swastika," Heller writes in an opening chapter. From the Indus Valley to ancient Troy to Native American cultures, the swastika, in various configurations, had been—and continues to be—used on items both commonplace and sacred, almost always as a sign of benediction. Through World War I, the symbol was still prominent, including in Europe and the States, in architecture, on everyday consumables and in advertising.

Starting in the late 19th century, however, the symbol was appropriated by esoteric German occultists as a secret signifier, and was quickly linked to growing nationalist, white supremacist and anti-Semitic sentiments. It became, as Heller has put it, Hitler's instrument. It was not solely the mark of his political party but a personal emblem, his surrogate, the Third Reich aestheticized and in shorthand.

"That [Hitler] succeeded in transmuting an ancient symbol that had such long-lasting historical significance into one even more indelible—and in such a comparatively short period of time—is attributable to his complete mastery of the design and propaganda processes," Heller writes.

The second half of the book looks at the use of the swastika and related imagery post-World War II, as taken up by nascent nationalists after the fall of the Soviet Union, skinheads and neo-Nazis, ignorant designers, and, today, the alt-right. As Heller notes, "Many contemporary hate markers are rooted in Nazi iconography both as serious homage and sarcastic digital bots and trolls."

The Internet, particularly our social media-fueled version of it, has created a new ecosystem for hate speech and symbols, all of which can be rapidly produced, trafficked and consumed, at times unwittingly. If, as Heller writes, "symbolism plays a huge role in propagating unsavory ideas," then recognizing those symbols for what they are, is critical.

"I think the more information out there, the better," he says. "But does that mean that information is being digested?" When dealing with the dissemination of troubling designs, the slipperiness of online accountability and the contrarian, rebellious and disingenuous attitude of many of these symbols' users doesn't make the distinctions between malice, a joke or an honest mistake any clearer.

"In any case, the intent is not the issue; history is," he writes. Heller is known for his in-depth knowledge of design history. At SVA, he lectures on the history of graphic design and illustration. Throughout the book, Heller is emphatic that the past not be forgotten, or re-branded. He stresses the now-crucial mnemonic function of the swastika, as the number of those who lived through Nazi atrocities grows fewer, or as memes and misinformation campaigns diminish the severity of the intolerance and injustice, it stands for.

"This is a book that has been designed about a symbol that is being constantly designed, but it's not about design per se," Heller says. "It's about a totality of meaning, context and presentation."

"I can't predict how [the book is] going to be used, and I can't even say how I want it to be used except that I hope it brings people to talking about the symbol."